In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

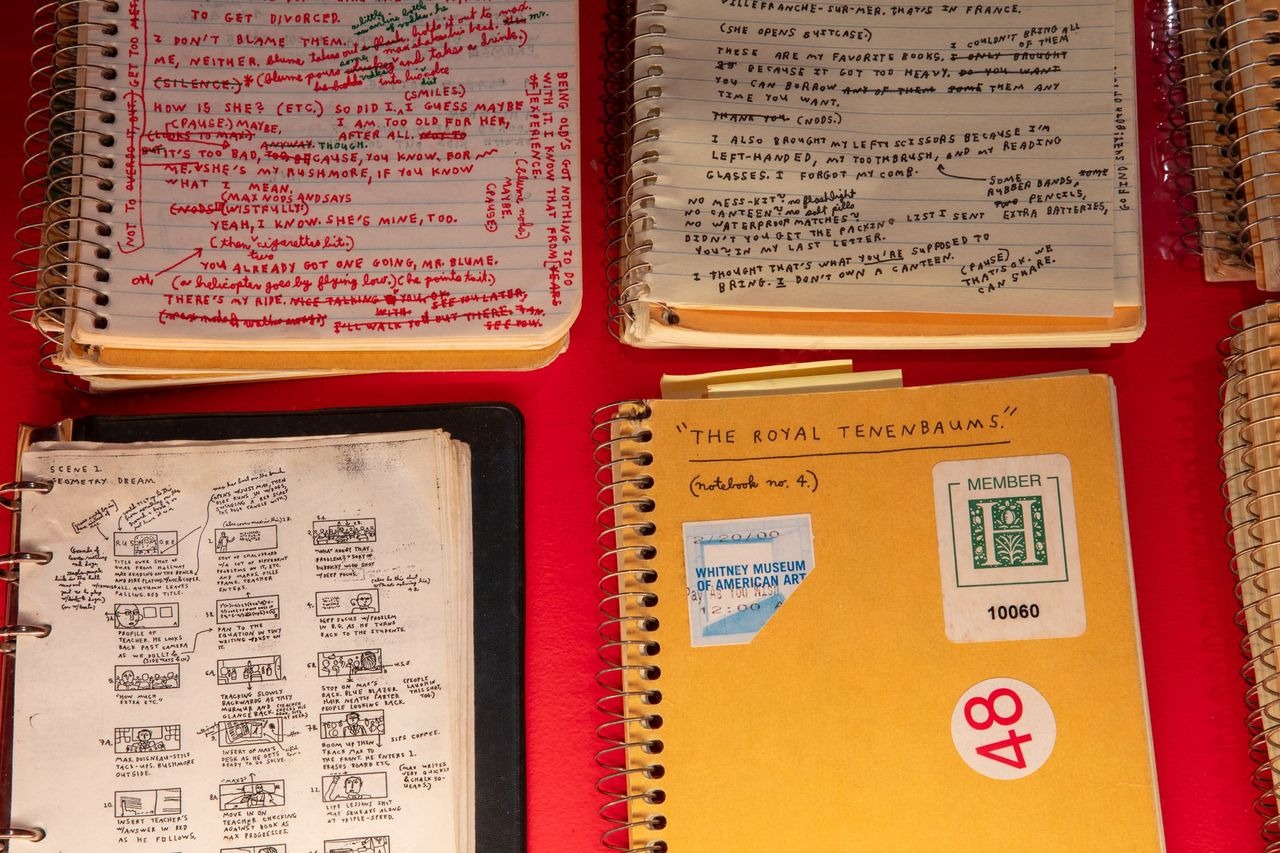

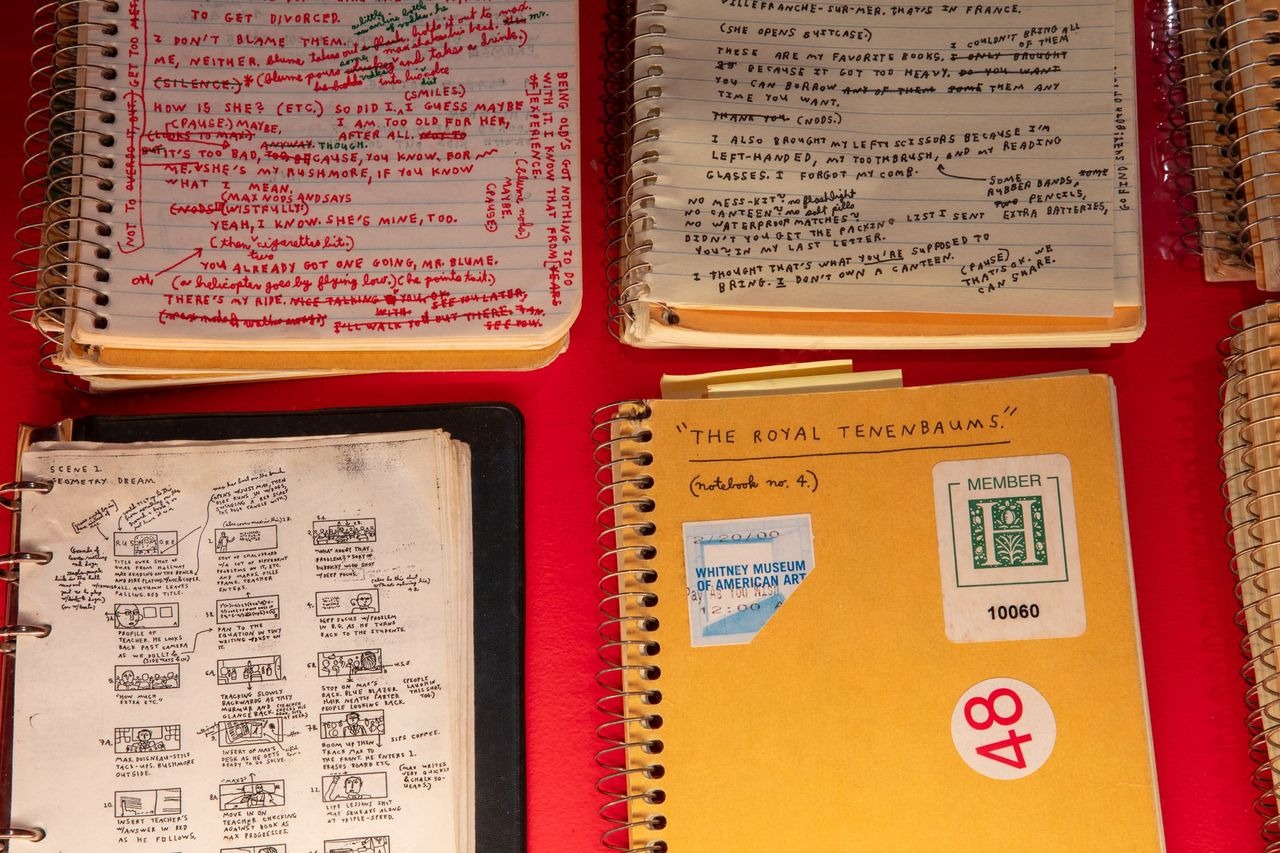

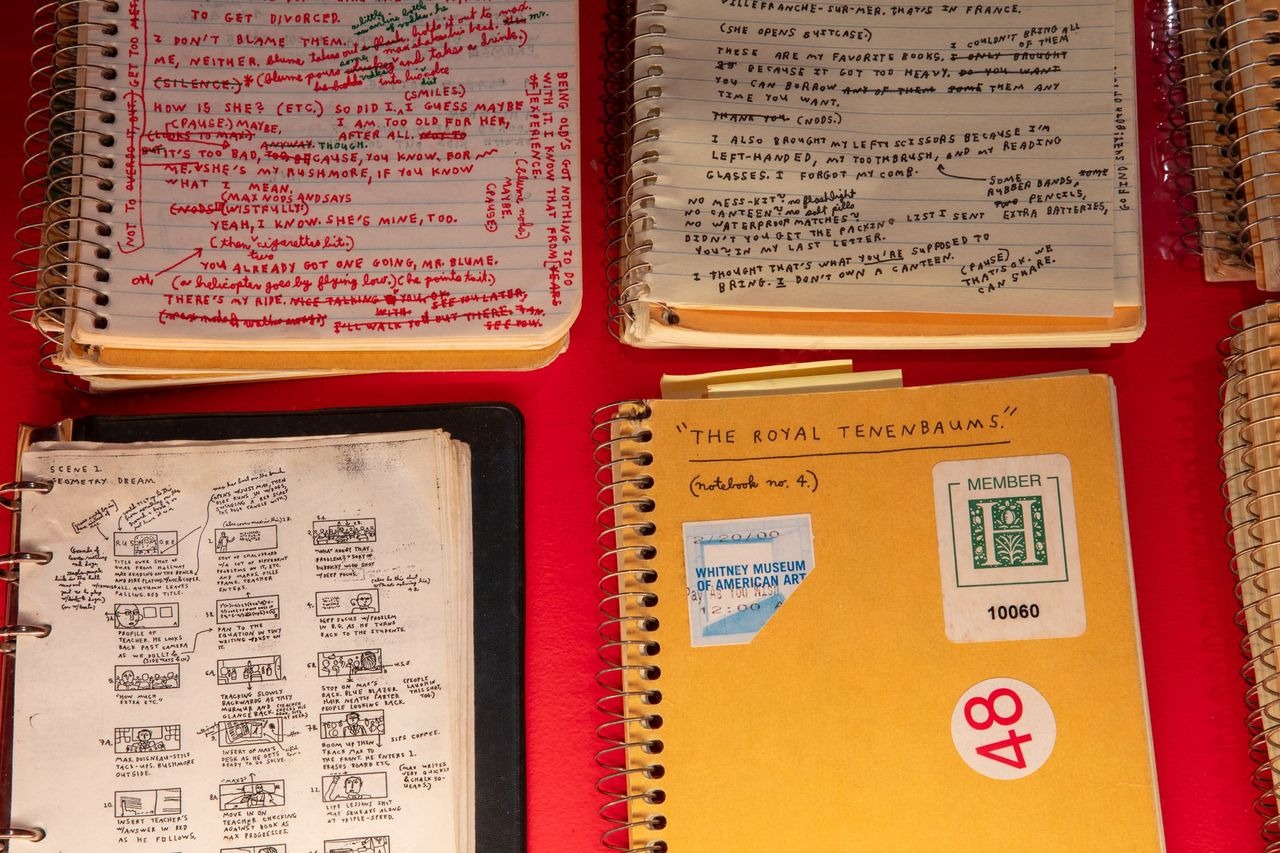

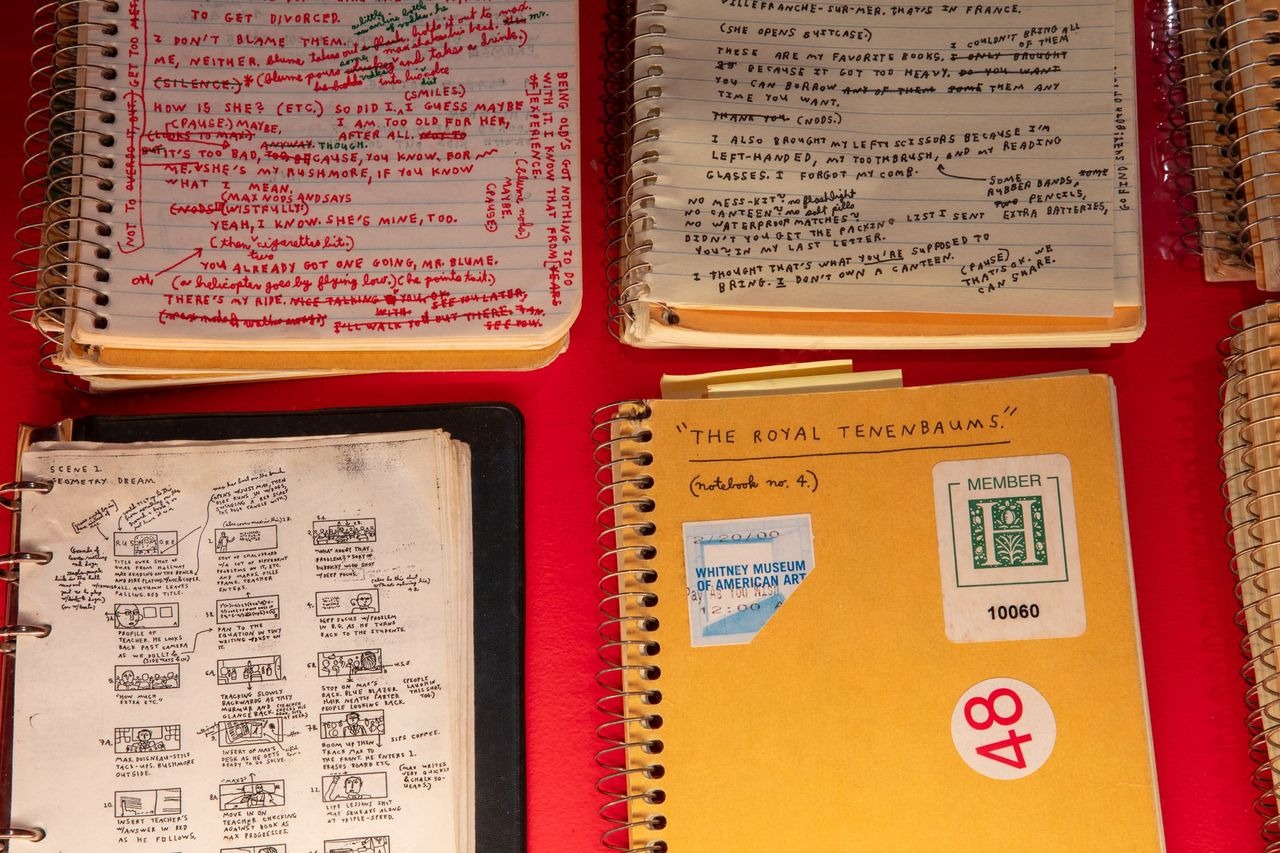

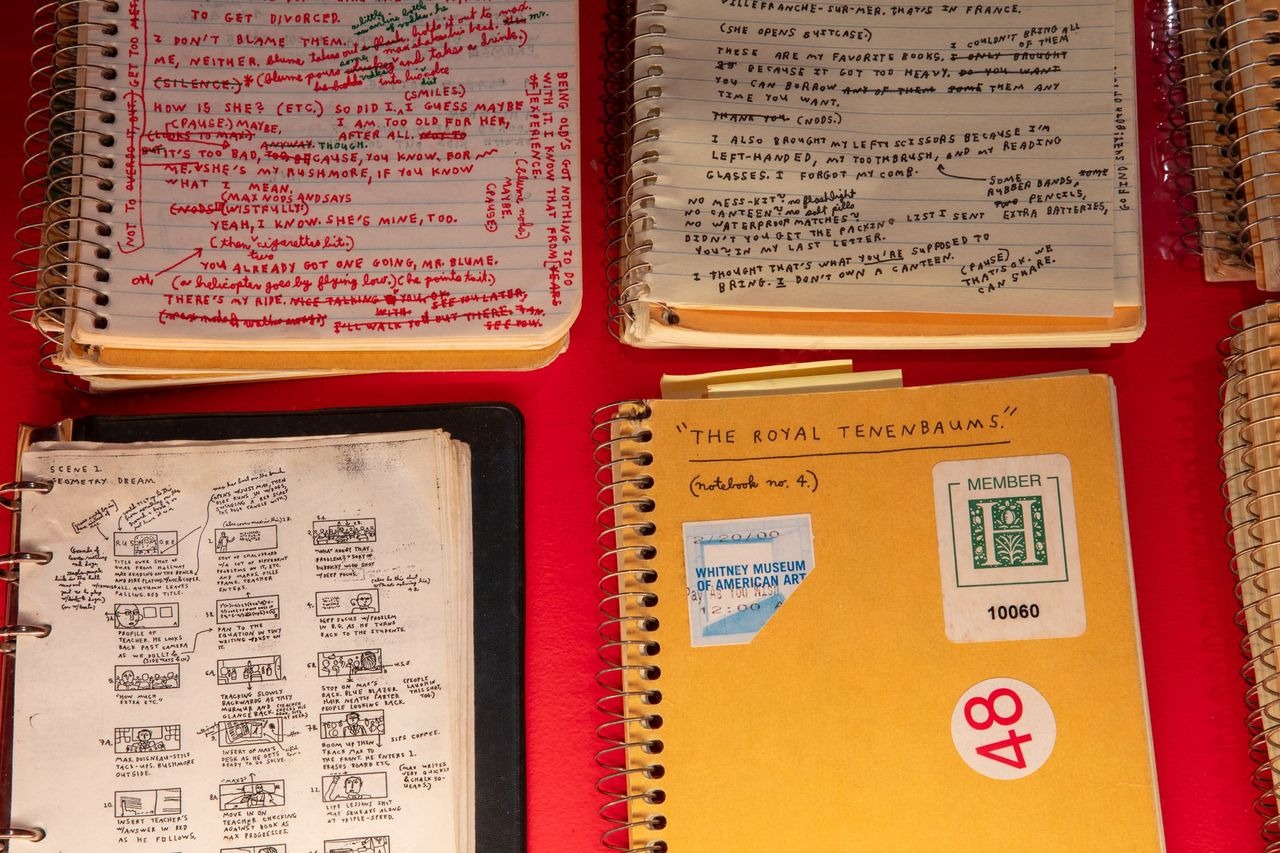

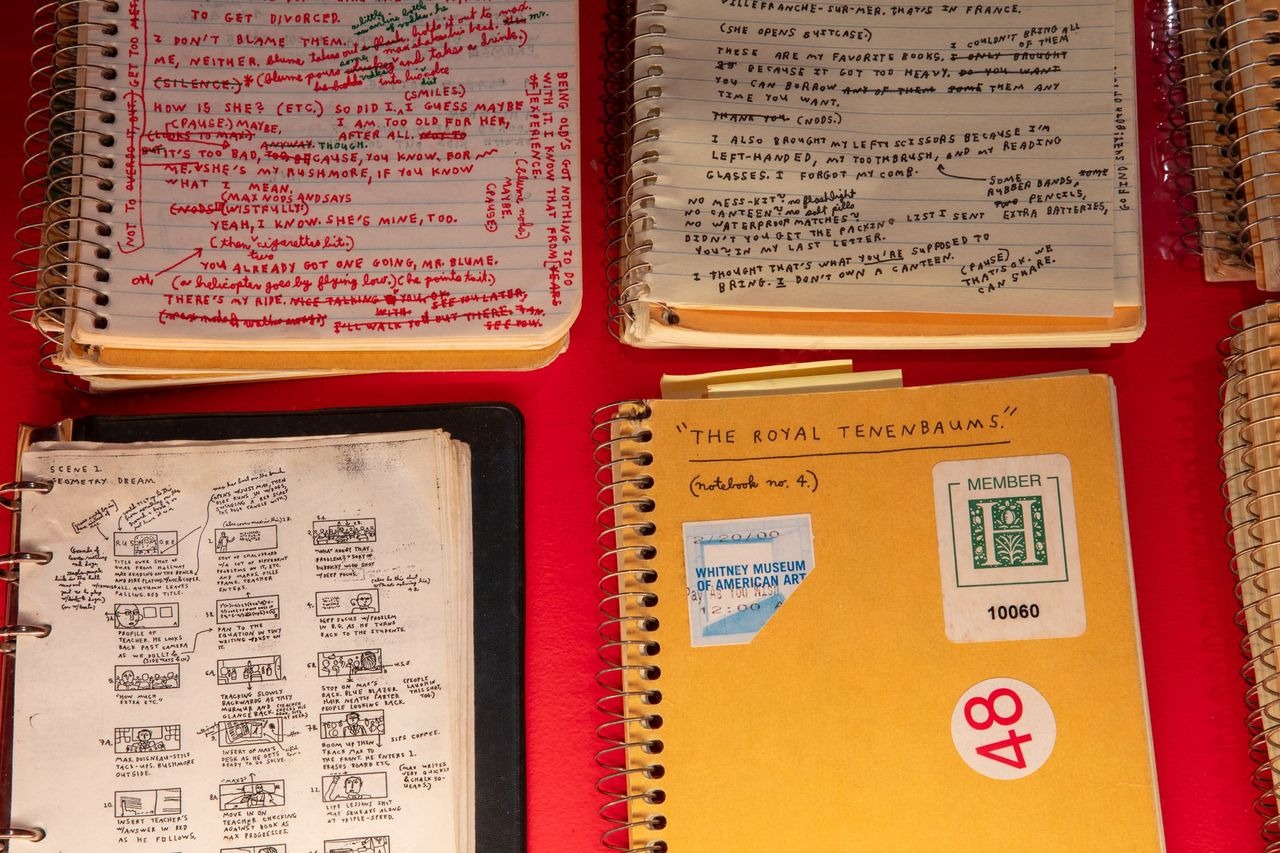

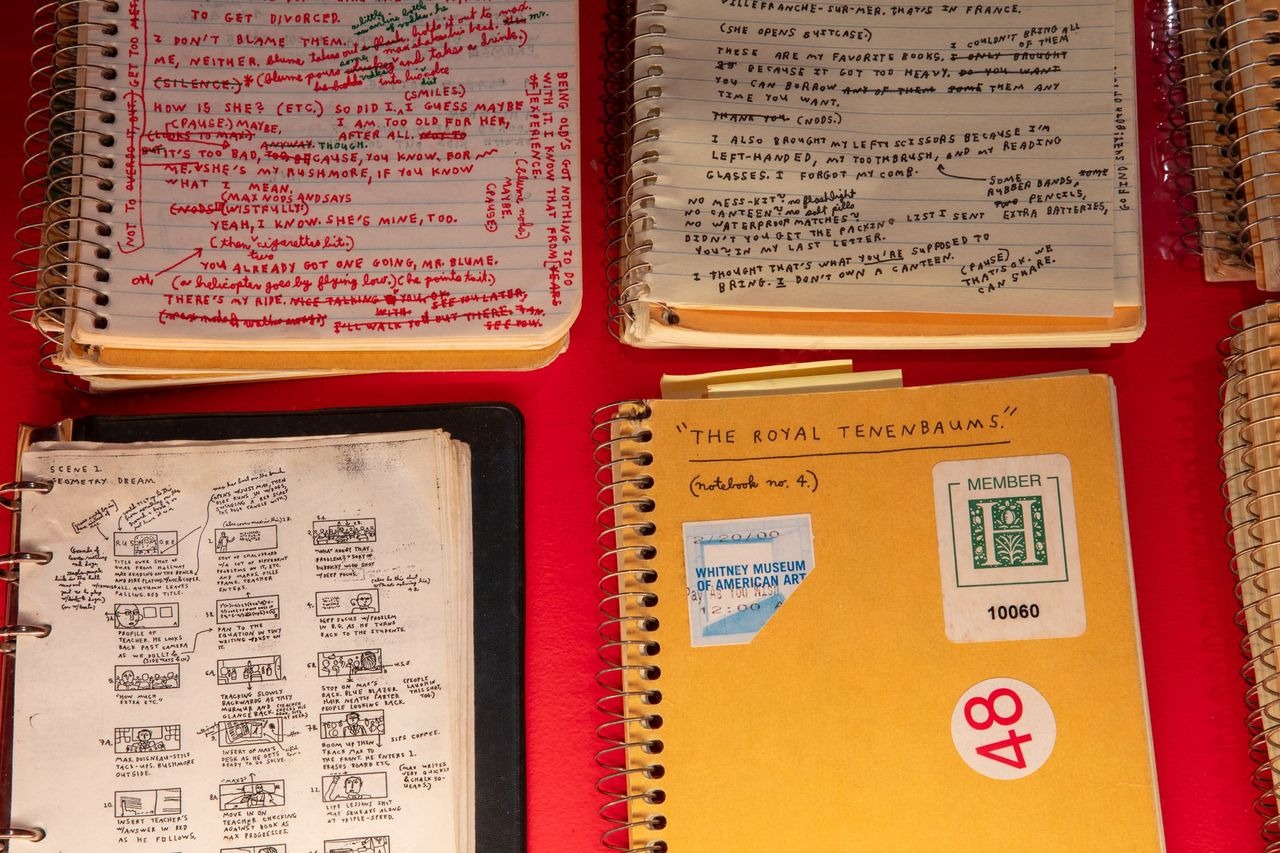

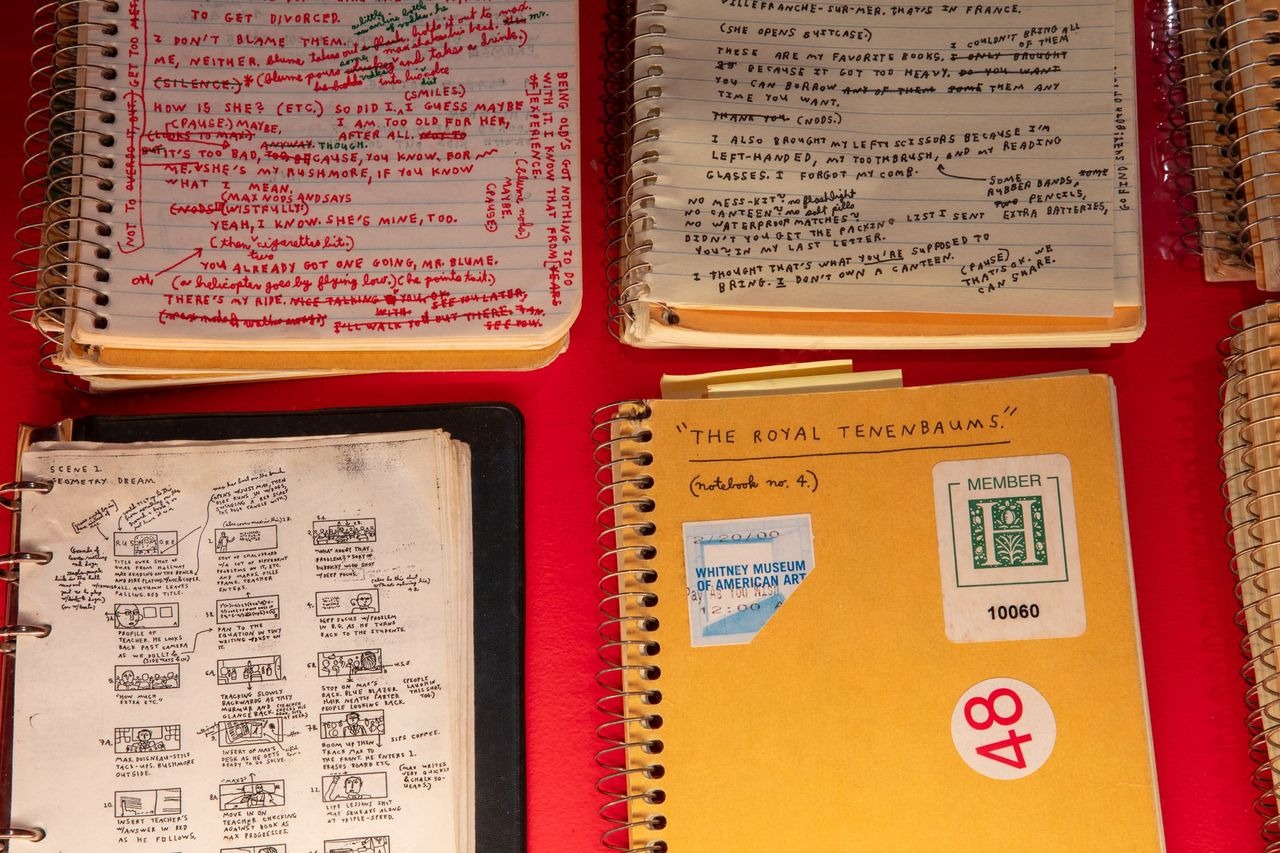

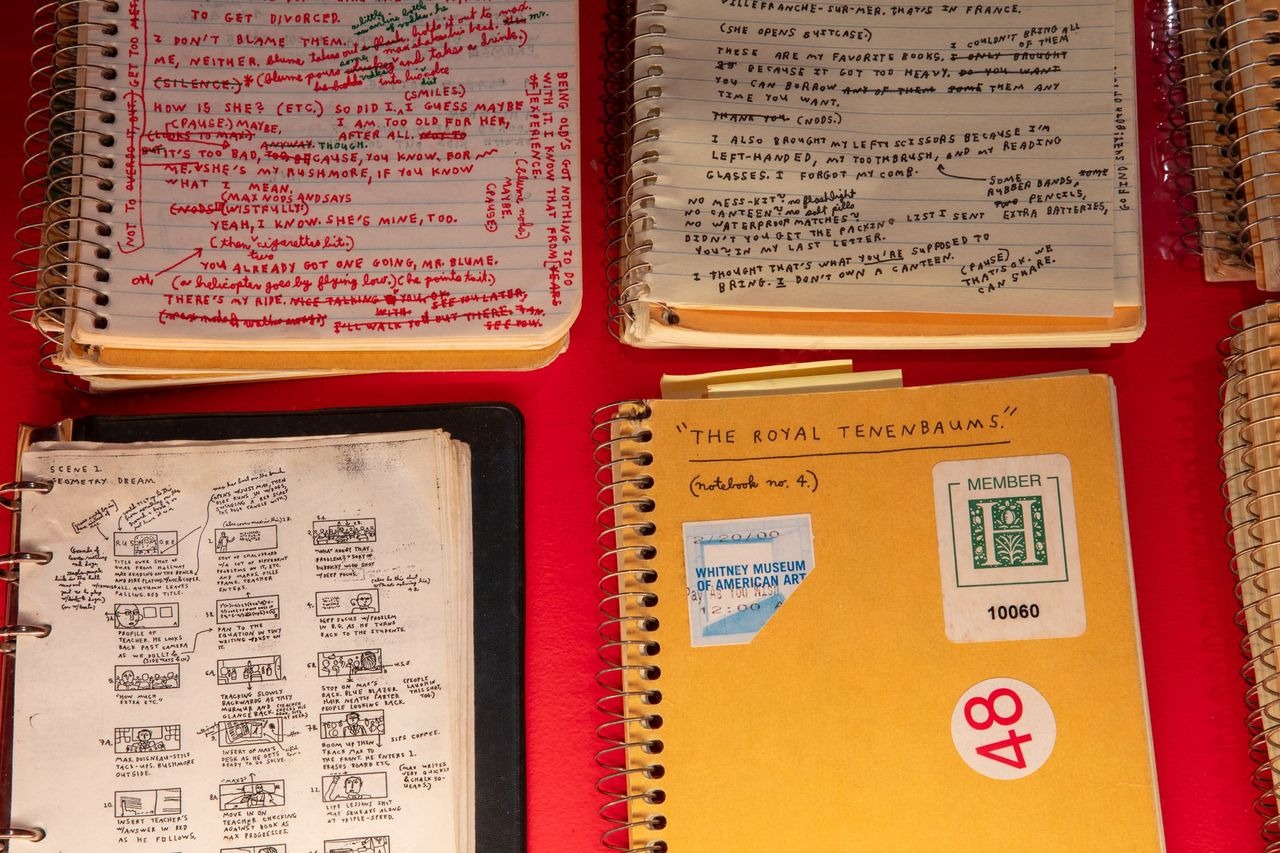

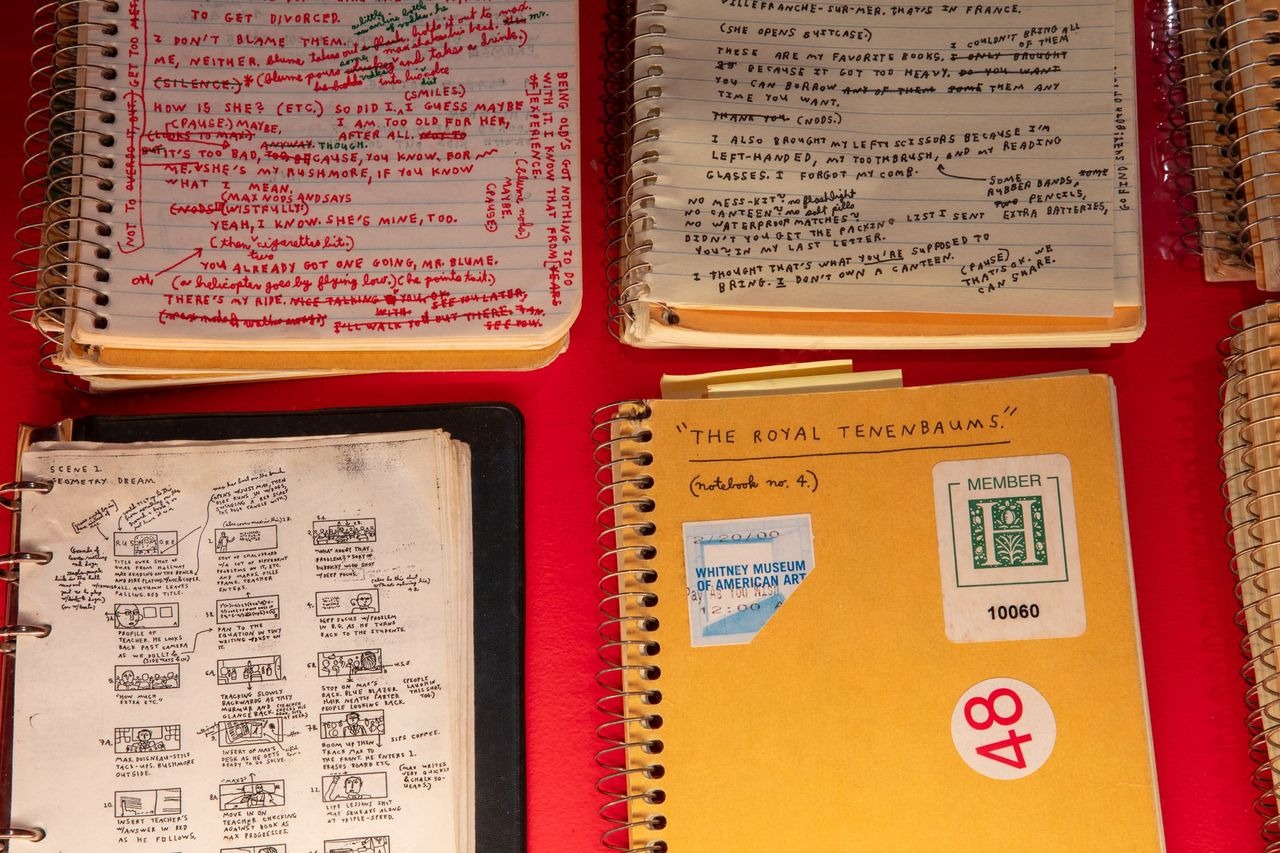

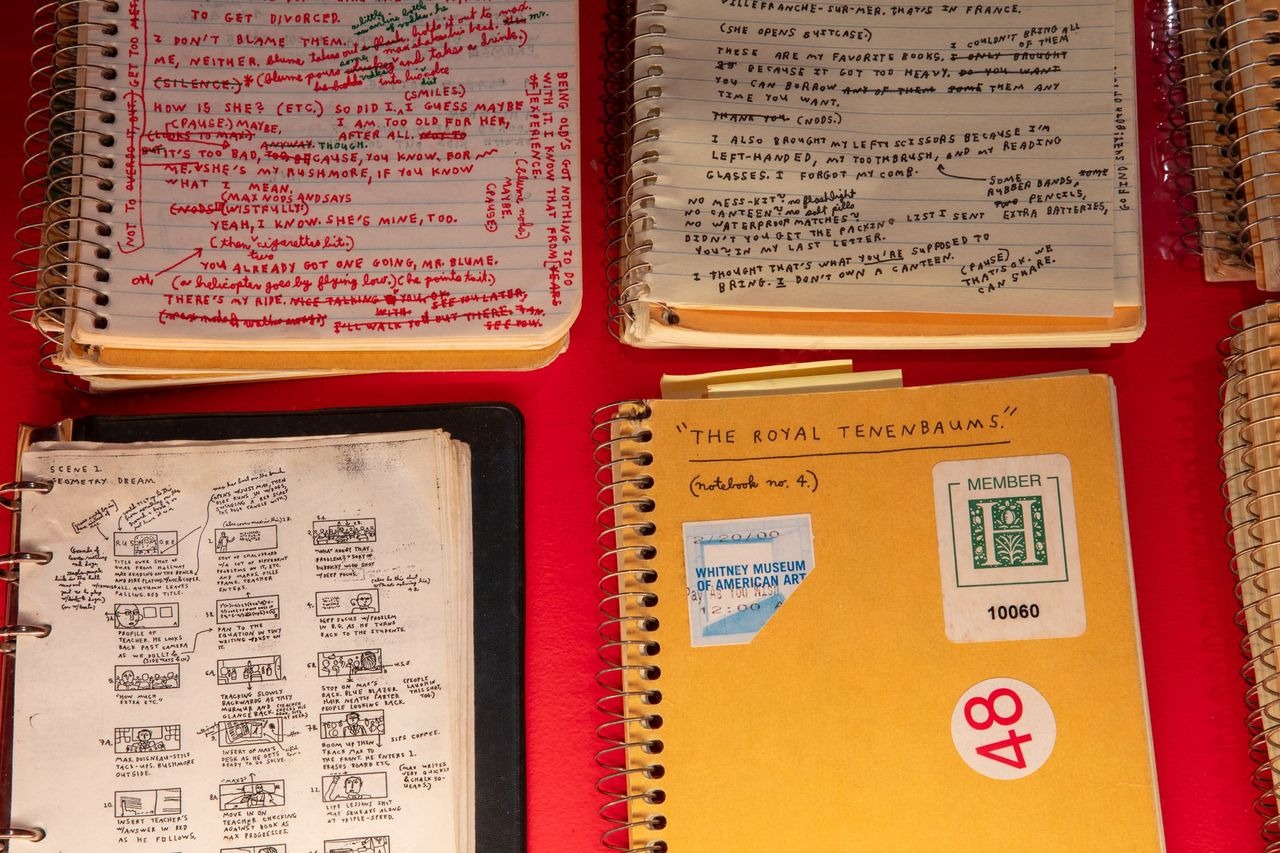

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.

In ‘The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner’, the final segment of Wes Anderson’s 2021 anthology film The French Dispatch, food critic Roebuck Wright confides in the audience that “I can neither comprehend nor describe what occurs behind a kitchen door. I have always been content to enjoy the issue of an artist’s talent without unveiling the secrets of the chisel or the turpentine”. The opening of Wes Anderson: The Archives at The Design Museum, composed of over 700 costumes, models and other ephemera raided from the director’s almost thirty-year archive, suggests that Anderson has no such compunctions in revealing his creative process - though there is a slight sense of trepidation in approaching the display. While it is tempting to peek behind the curtain of every meticulously composed shot, will doing so actually increase our enjoyment of them? Or should we prefer to simply enjoy them as the regular cinematic confections that they have become?

Much parodied but never bettered, Anderson’s work slots neatly alongside Wong Kar-wai, Hayao Miyazaki and Roy Andersson as artists whose visual style is recognisable from a single frame. This distinct mode of visual storytelling, owing as much to framing and movement as design, is surprisingly difficult to transition to an exhibition space; 180 Studios’ semi-regular exhibitions coinciding with each new Anderson release, in particular, are organised so haphazardly as to strip most of the life out of their exhibits, feeling more like cynical Instagram opportunities than true celebrations.

Fortunately, the Design Museum’s exhibition is the complete opposite; while the exhibition highlights, particularly the 3-metre-wide façade of the Grand Budapest, are natural photo opportunities, the exhibition itself is far more a celebration of the sheer work that goes into making these films. Detractors of Anderson frequently suggest that aesthetic whimsy is utilised in his films in place of character, a notion which this show thoroughly dispels. A selection of Suzy’s lovingly-illustrated library books barely glimpsed in Moonrise Kingdom; a brooch on the lapel of the Warris Ahluwalia’s officious train steward designed by Ahluwalia himself in The Darjeeling Limited; a Rushmore school badge made by Jason Schwartzman ahead of his lead role in Anderson’s second feature; each of these objects stand as a testament not just to Anderson’s craft and attention to detail, but his ability to create cinematic worlds that feel like natural extensions of the characters within them.

Rather than dulling the magic of the director’s work, the opening up of Anderson’s filmmaking process only feels more alive. Even behind-the-scenes materials are vibrant with character, with an early draft script for Rushmore adorned not just with reworked lines and edits, but doodles and in-character graffiti proclaiming ‘MAX FISHER UNITED’, as if in character as the film’s precocious wannabe rebel. This prioritisation of character above all else is perhaps best exemplified in a series of LAVs (Live Action Videos) of Anderson himself acting out scenes from his two stop-motion films, Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, as visual references for the animators - maybe the most rewarding for any visitor who has watched his films enough times to know whole scenes word-for-word.

These visitors - the sort of Anderson Acolytes who obsessively pause at the beginning of each new frame to savour over the details, framing and design - are unquestionably the target audience for this exhibition. From the relatively subdued visuals of 1996’s Bottle Rocket through the hyper-controlled visuals of everything from Mr. Fox onwards, The Archives takes a (more-or-less) chronological approach, tracking the evolution of Anderson’s craft. With the photography of Jacques Henri Lartigue displayed alongside the montage of Max Fischer’s extracurricular activities and an oil painting of director and musician Satyajit Ray positioned above the miniature of The Darjeeling Limited’s titular train, the exhibition takes great pains to explore the director’s influences.

The recurrence of names, including co-writer Roman Coppola, musician Alexandre Desplat and graphic designer Erica Dorn, brings home the importance of collaboration at every stage of the director’s work. With Anderson and his team playing a central role in the curation of these mutually passionate collaborations - and to bring in the work of another American auteur - the exhibition brings to mind Elliot in Steven Spielberg’s E.T., excitedly showing off his toy collection to his new alien friend.

In a way, Wes Anderson: The Archives has opened at a perfect time; like any artist with a distinct visual style, the director’s work has become fodder for the trend of dull, uninspired interpretations by AI models, offering lifeless visuals and little else. In celebrating the level of design poured into every moment of these films, the exhibition doesn’t remove the magic from them; instead, it uses the human fingerprints on even the smallest designs as celebrations of creativity. If entering the exhibition felt like Roebuck Wright tentatively entering the kitchen, then leaving it feels like Stephen Park’s Chef Nescaffier, lost in reverie as his love of his chosen art form deepens.

Wes Anderson: The Archives is showing at The Design Museum until 26 July 2026.