Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

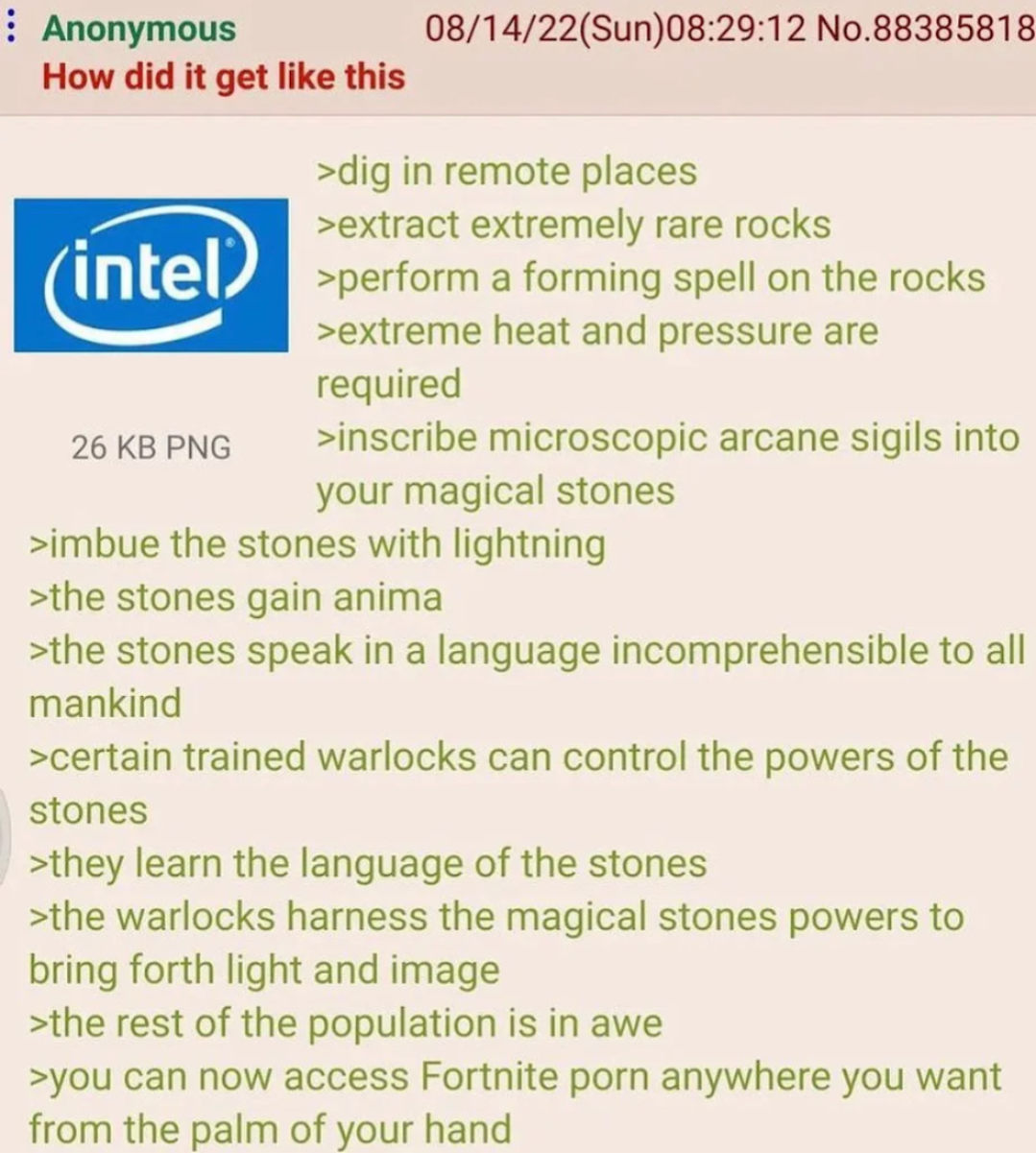

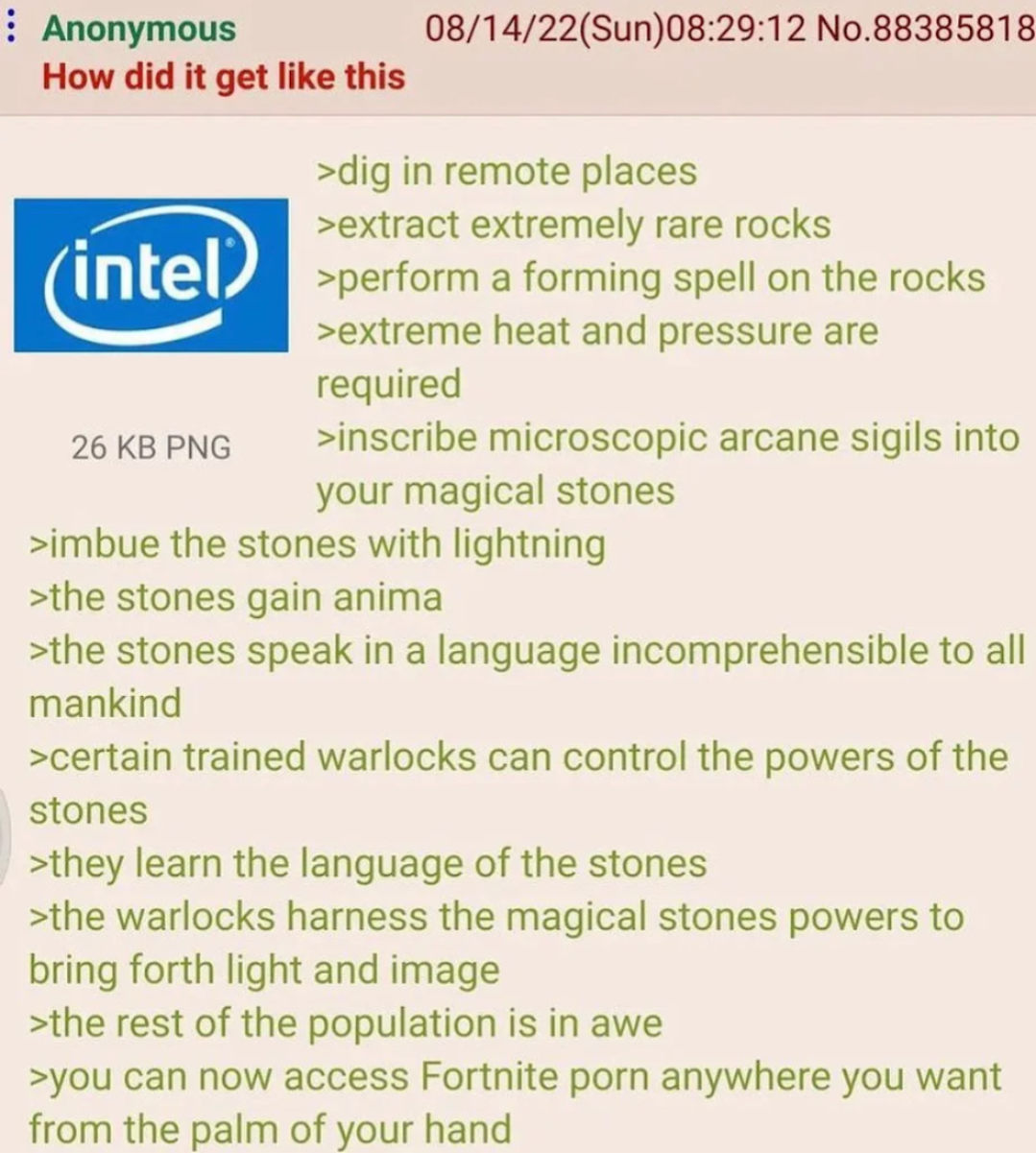

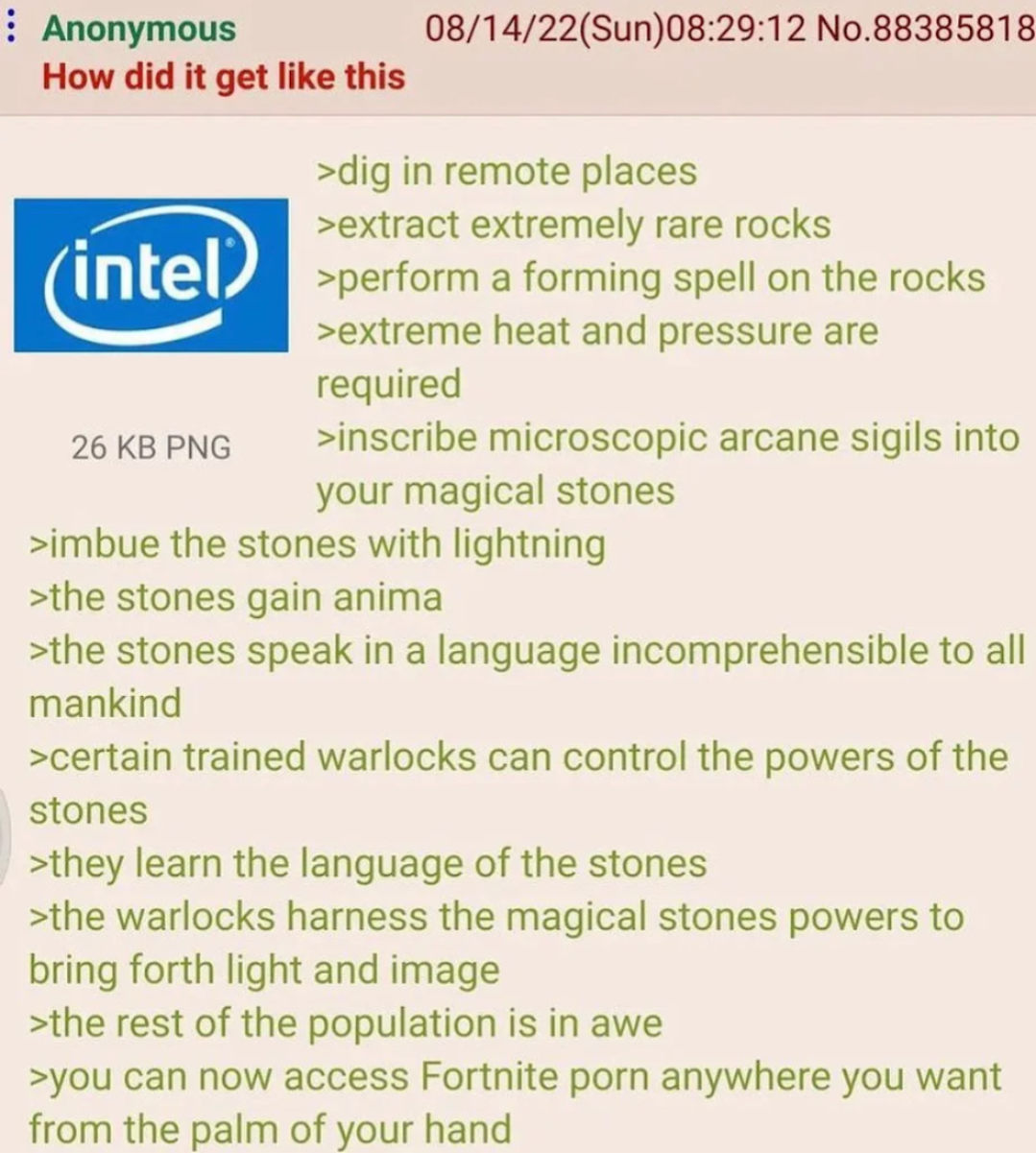

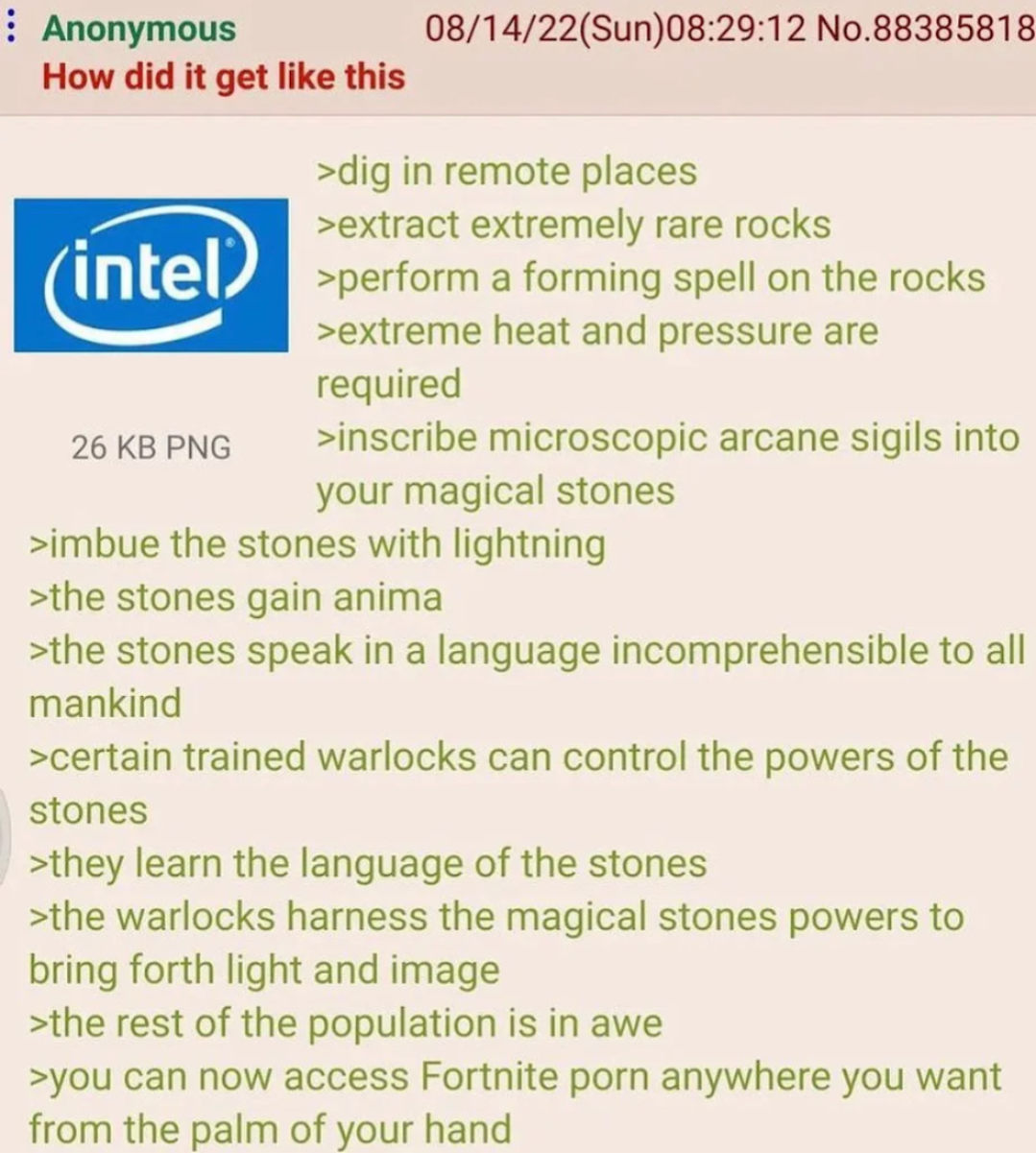

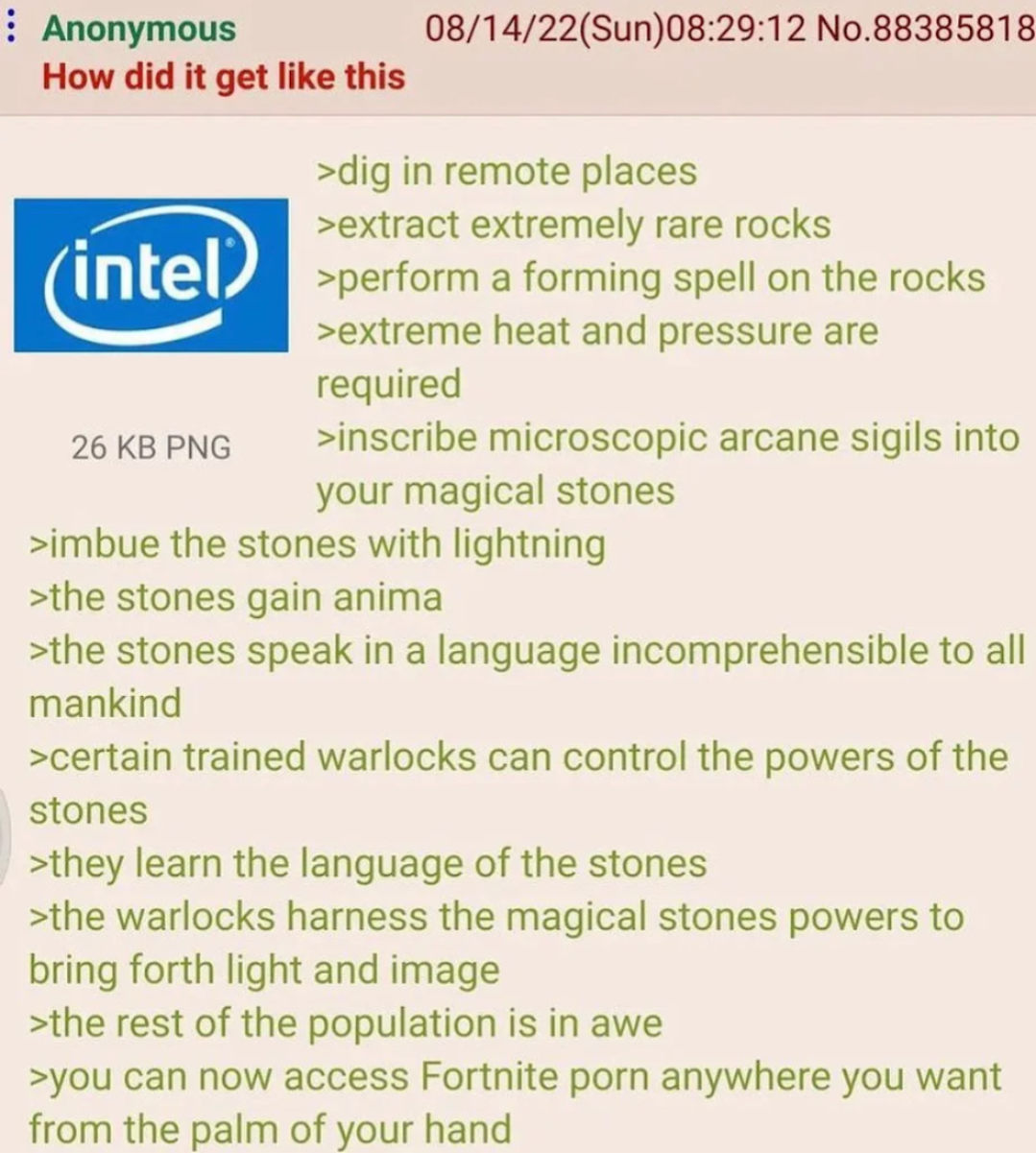

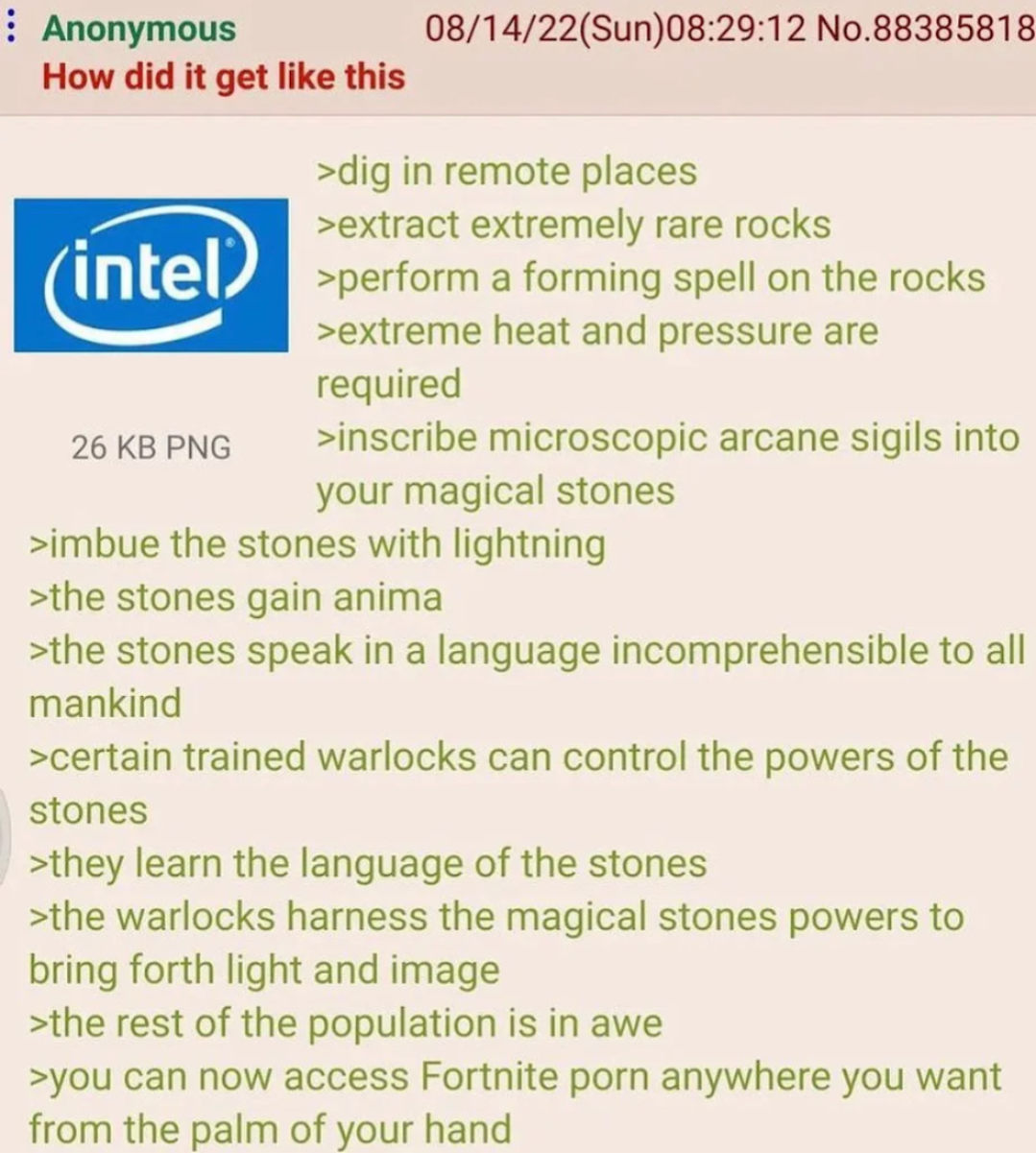

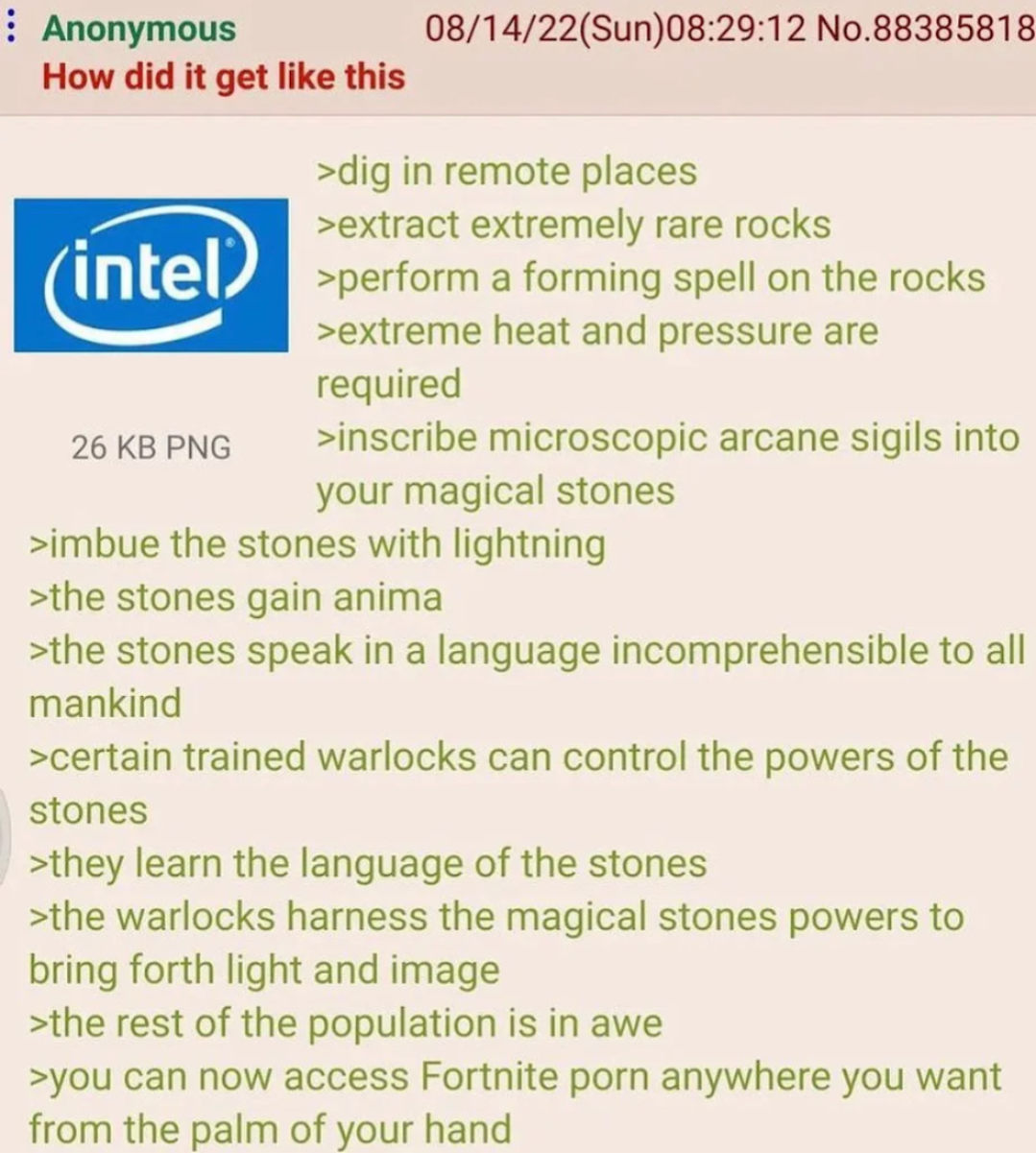

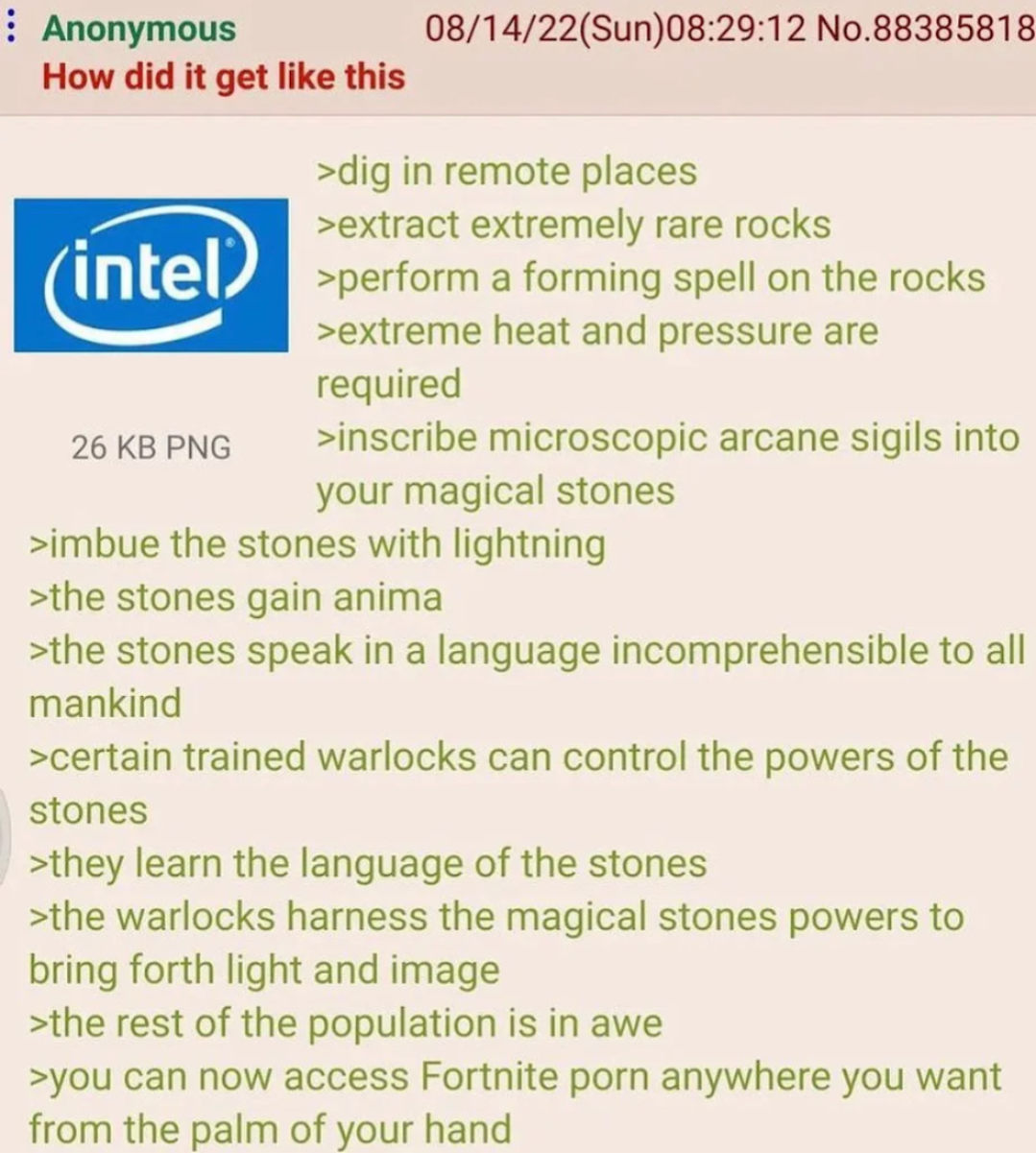

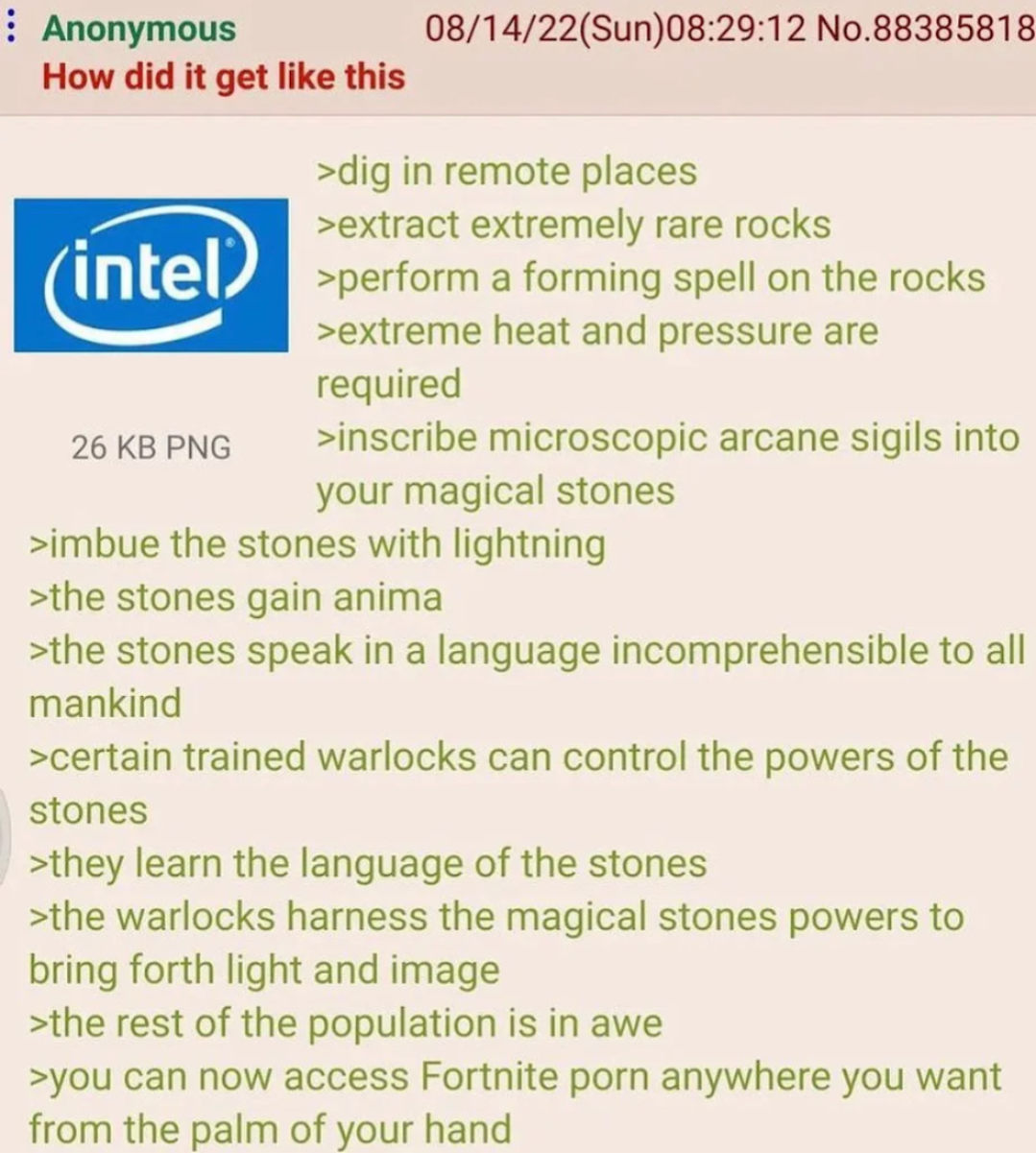

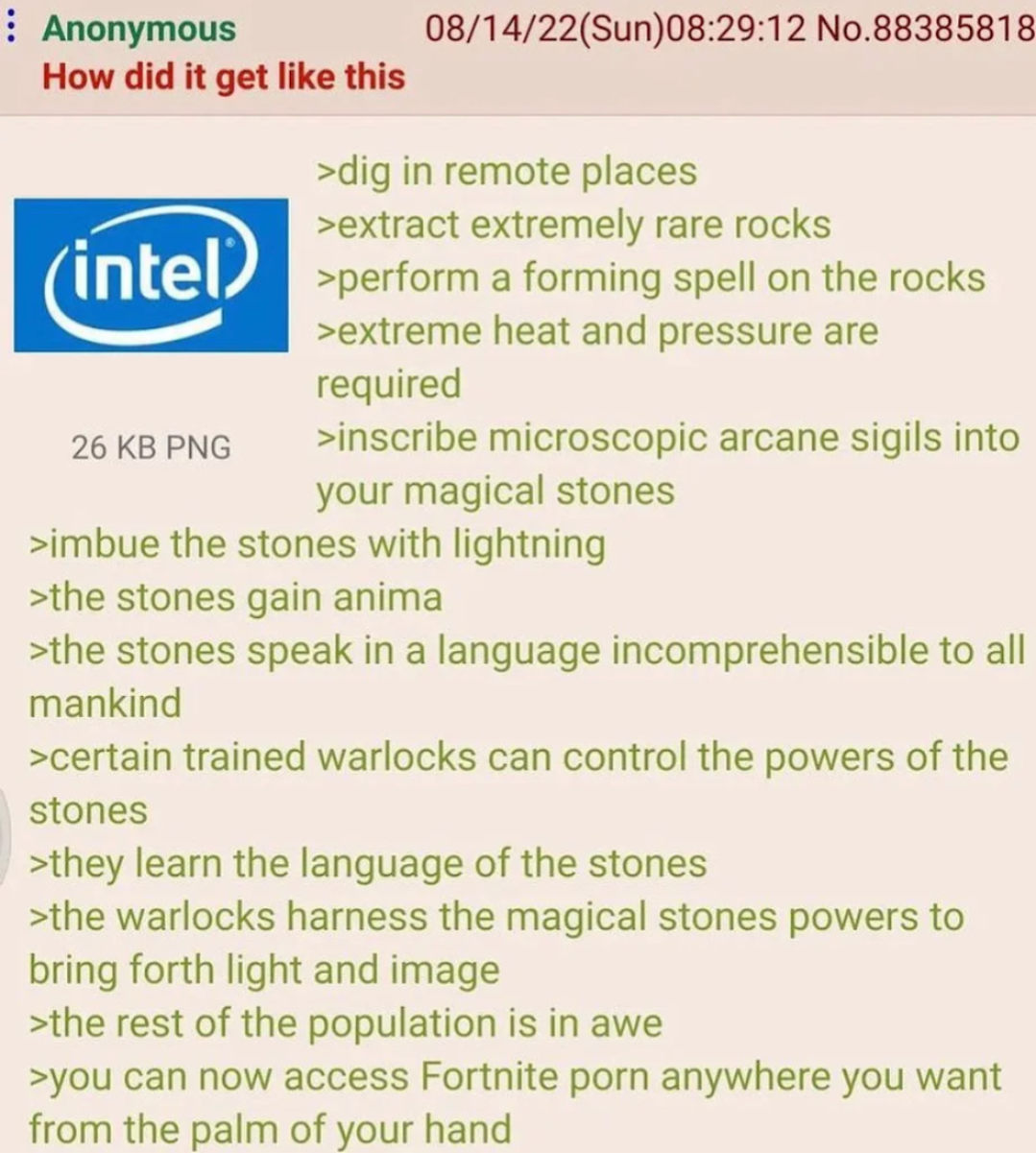

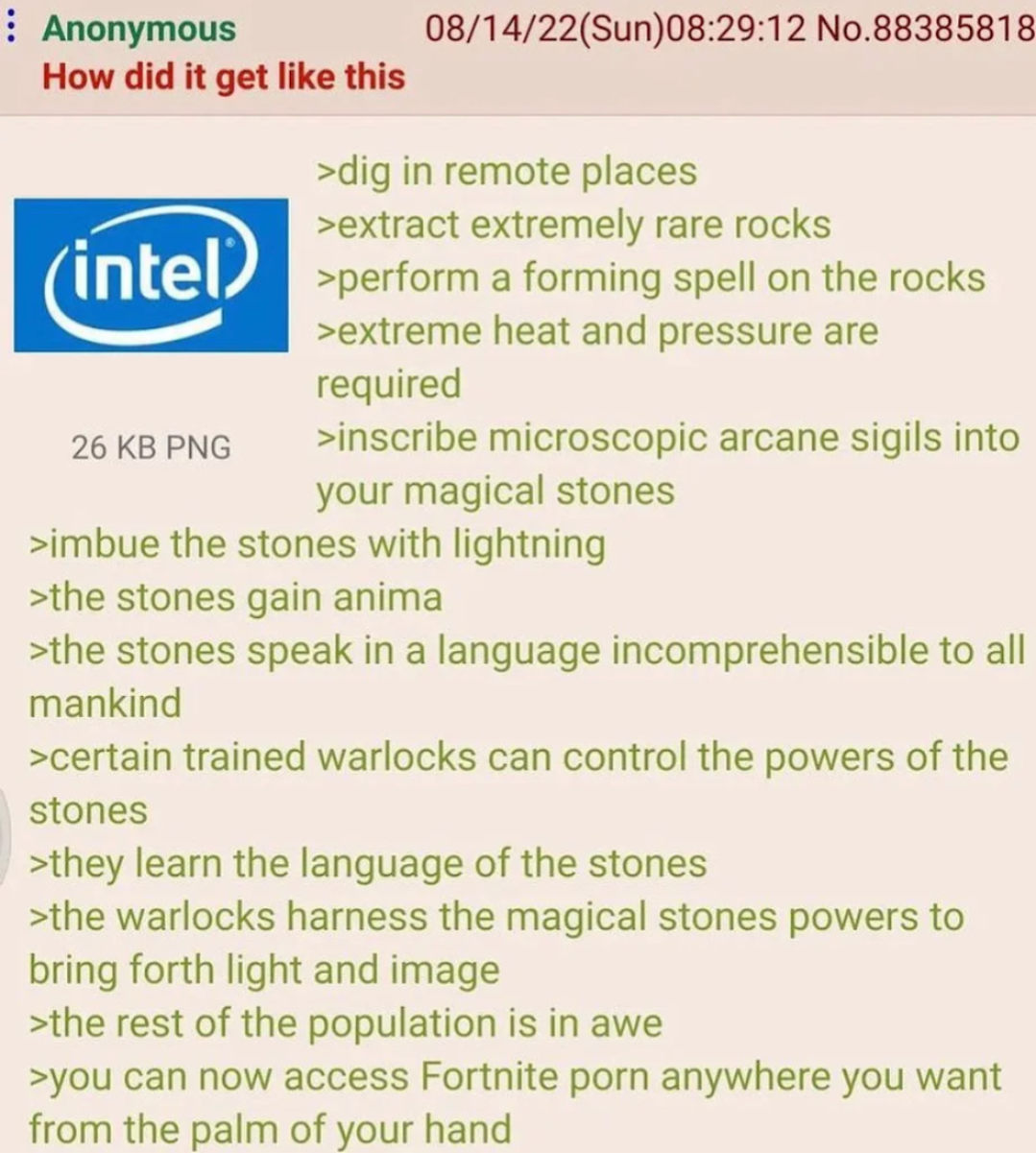

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

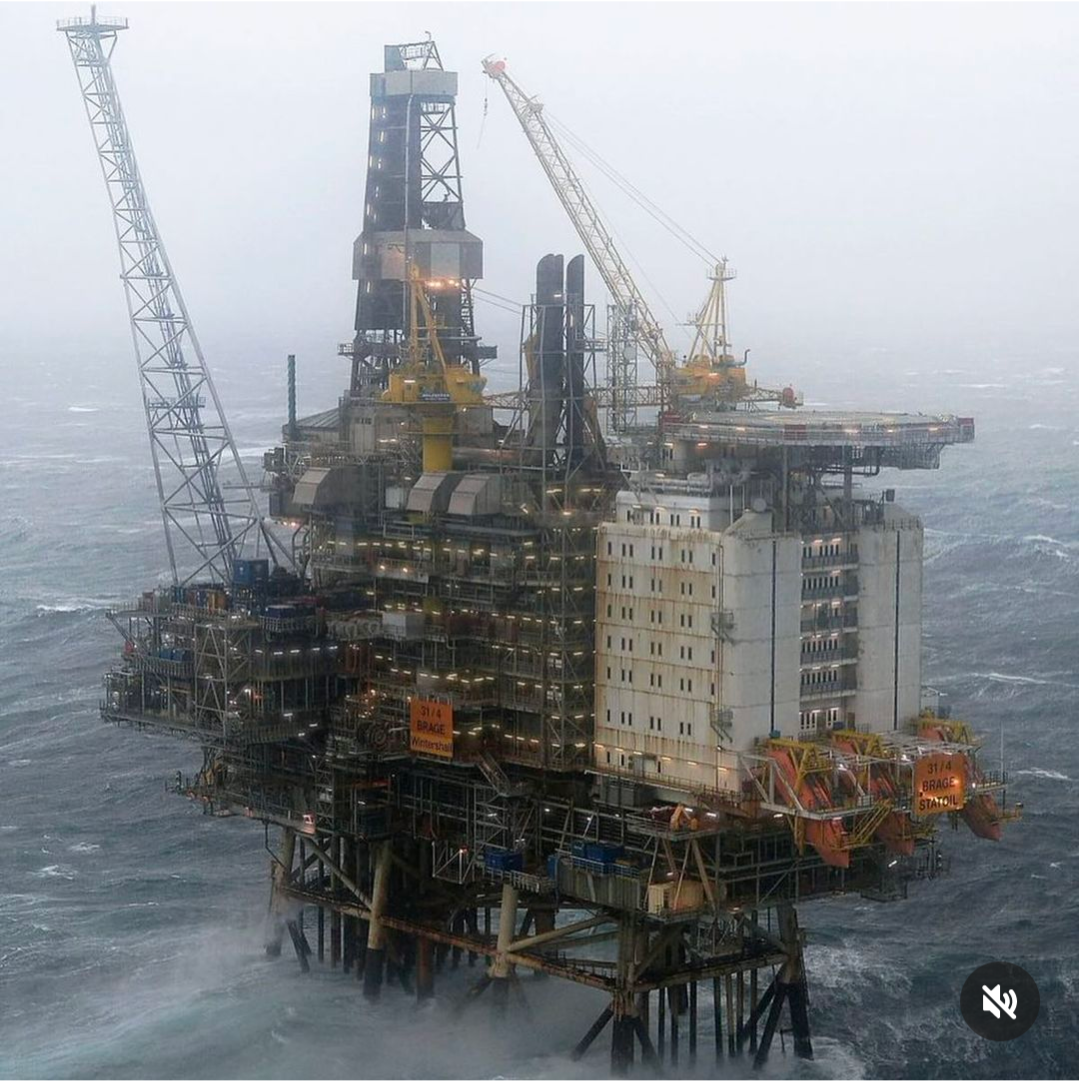

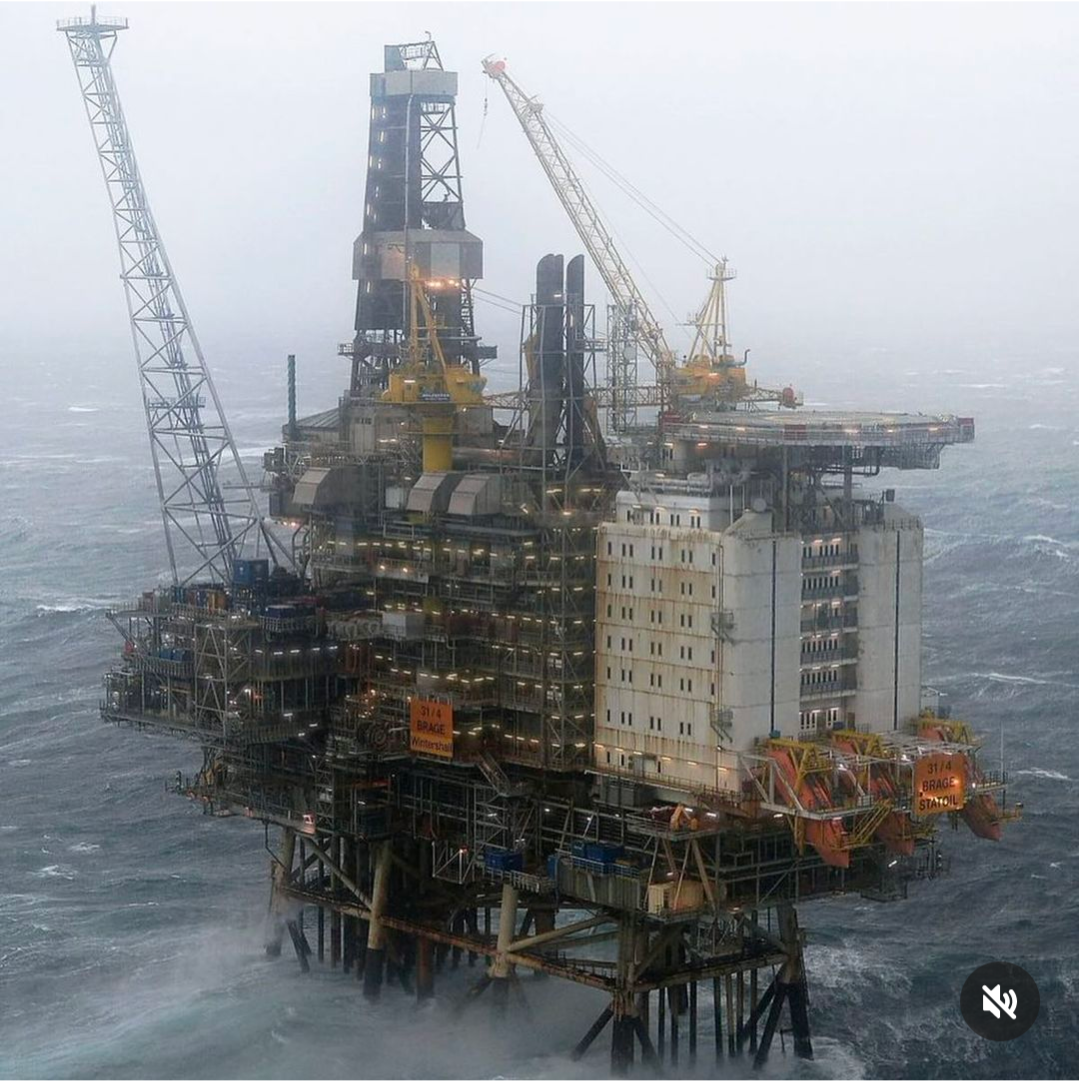

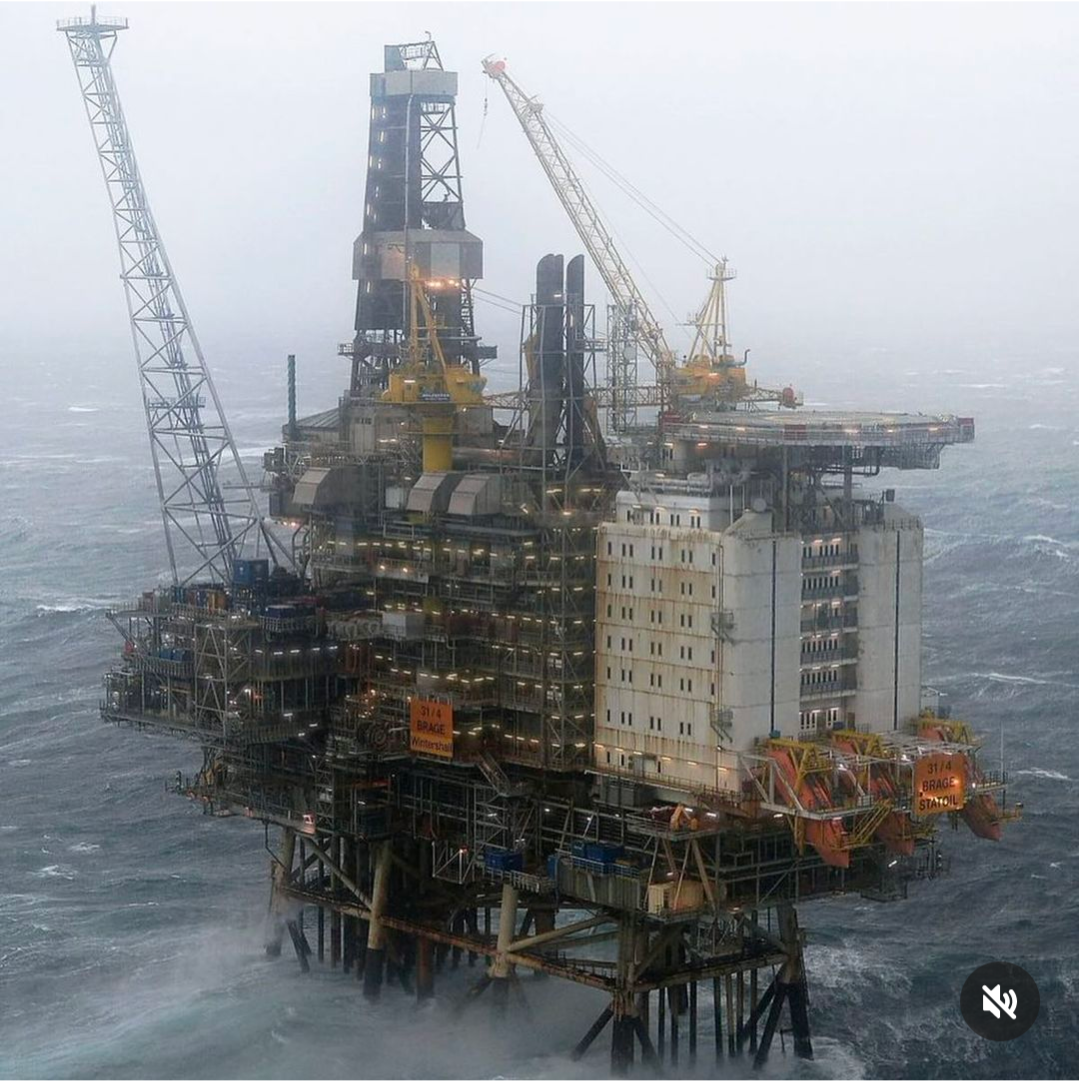

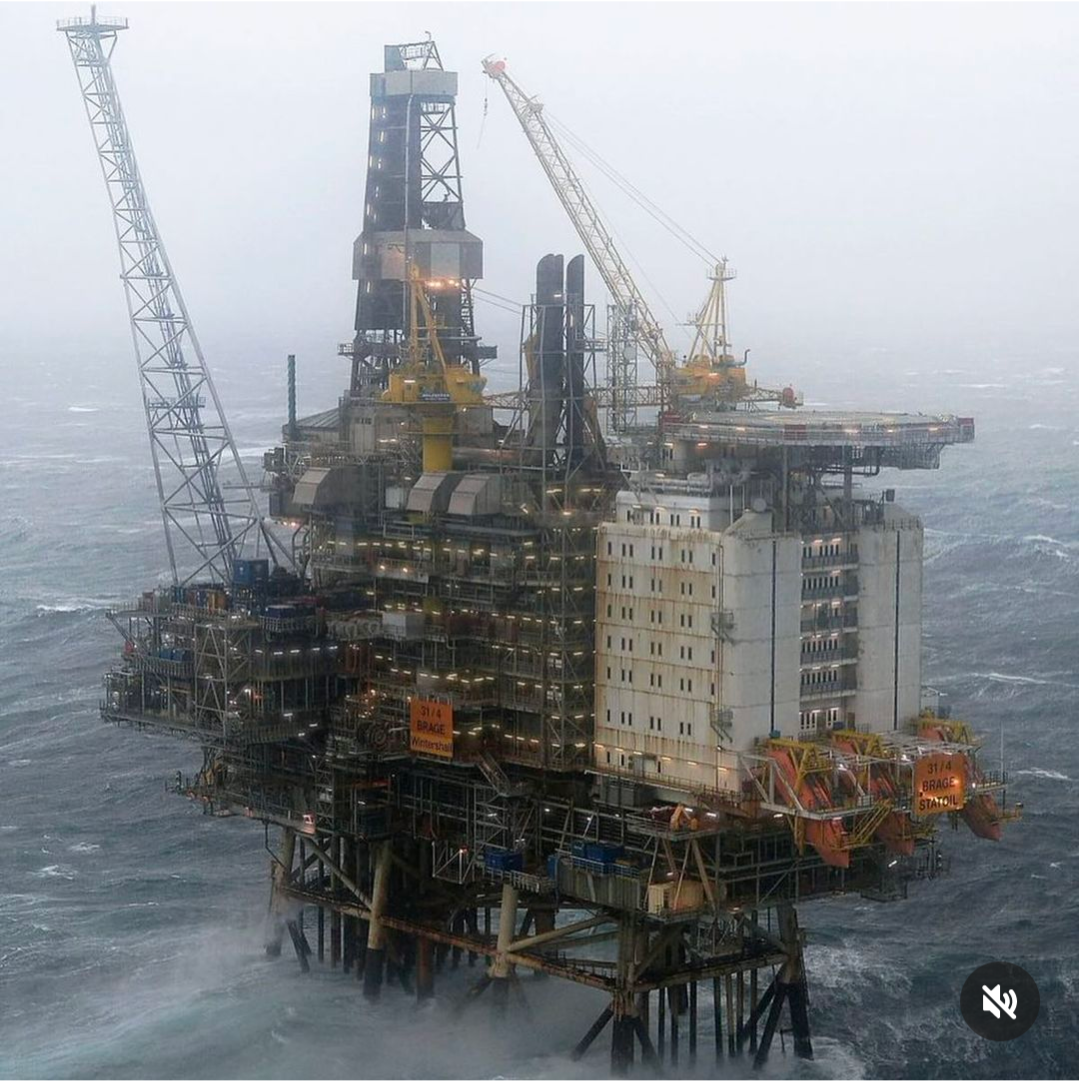

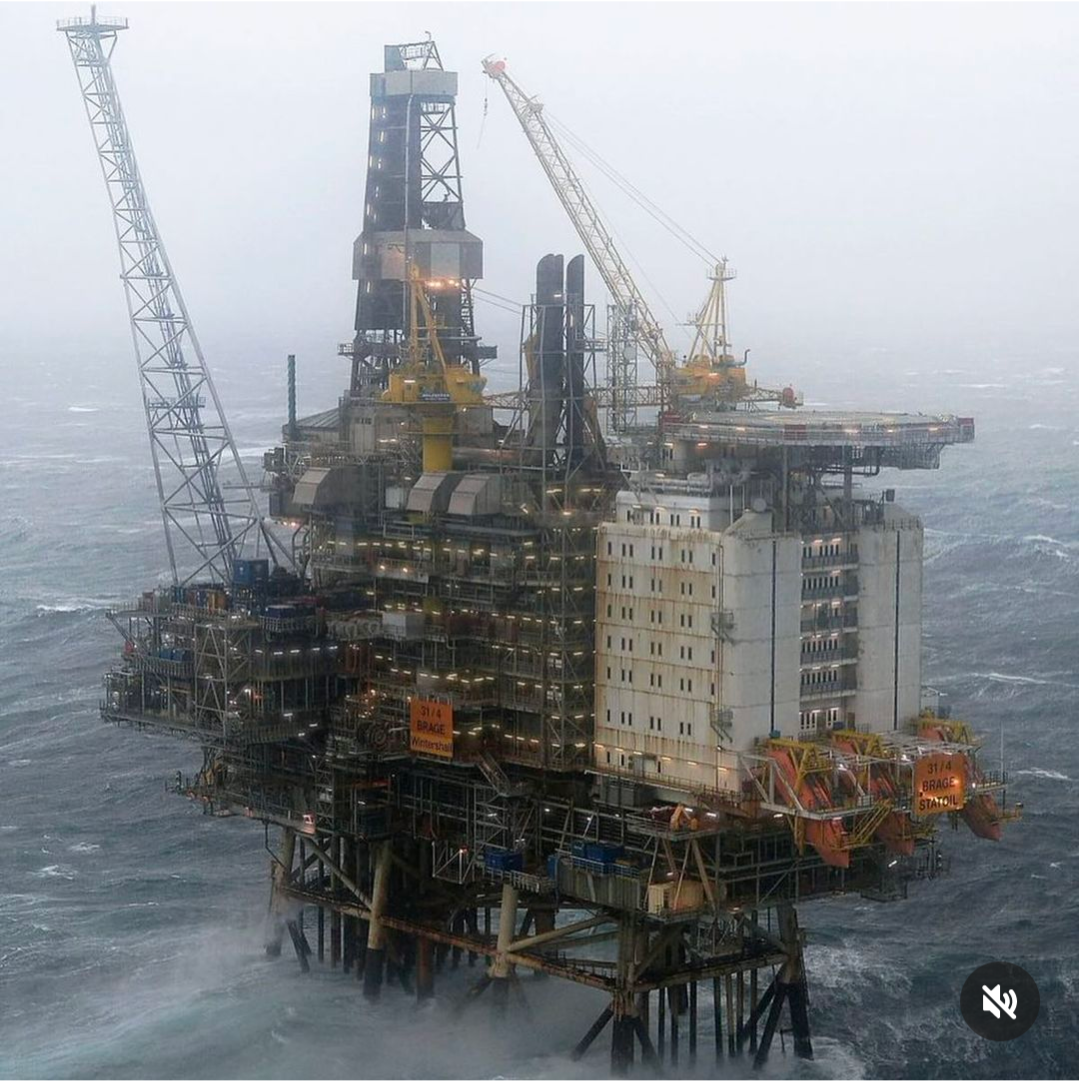

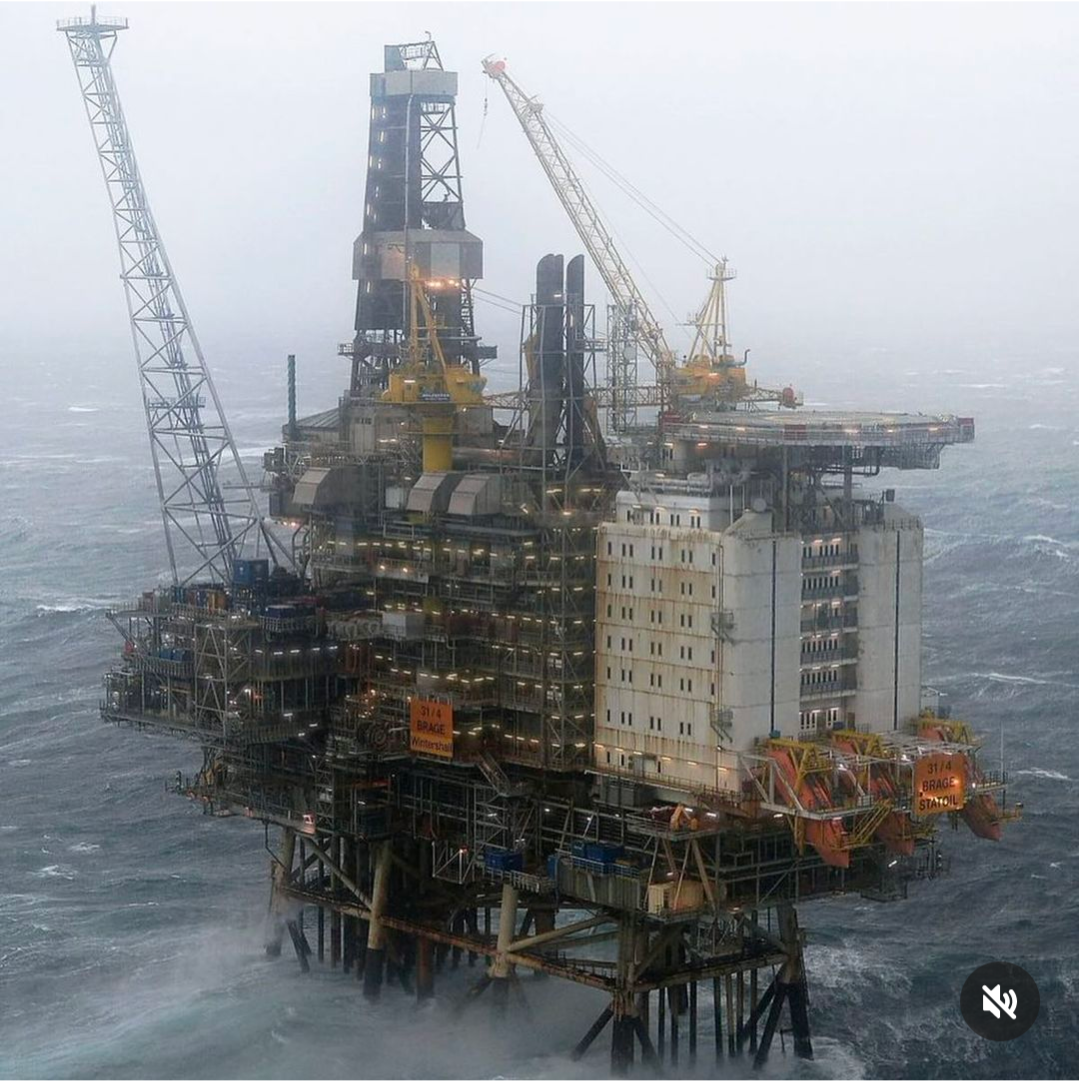

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

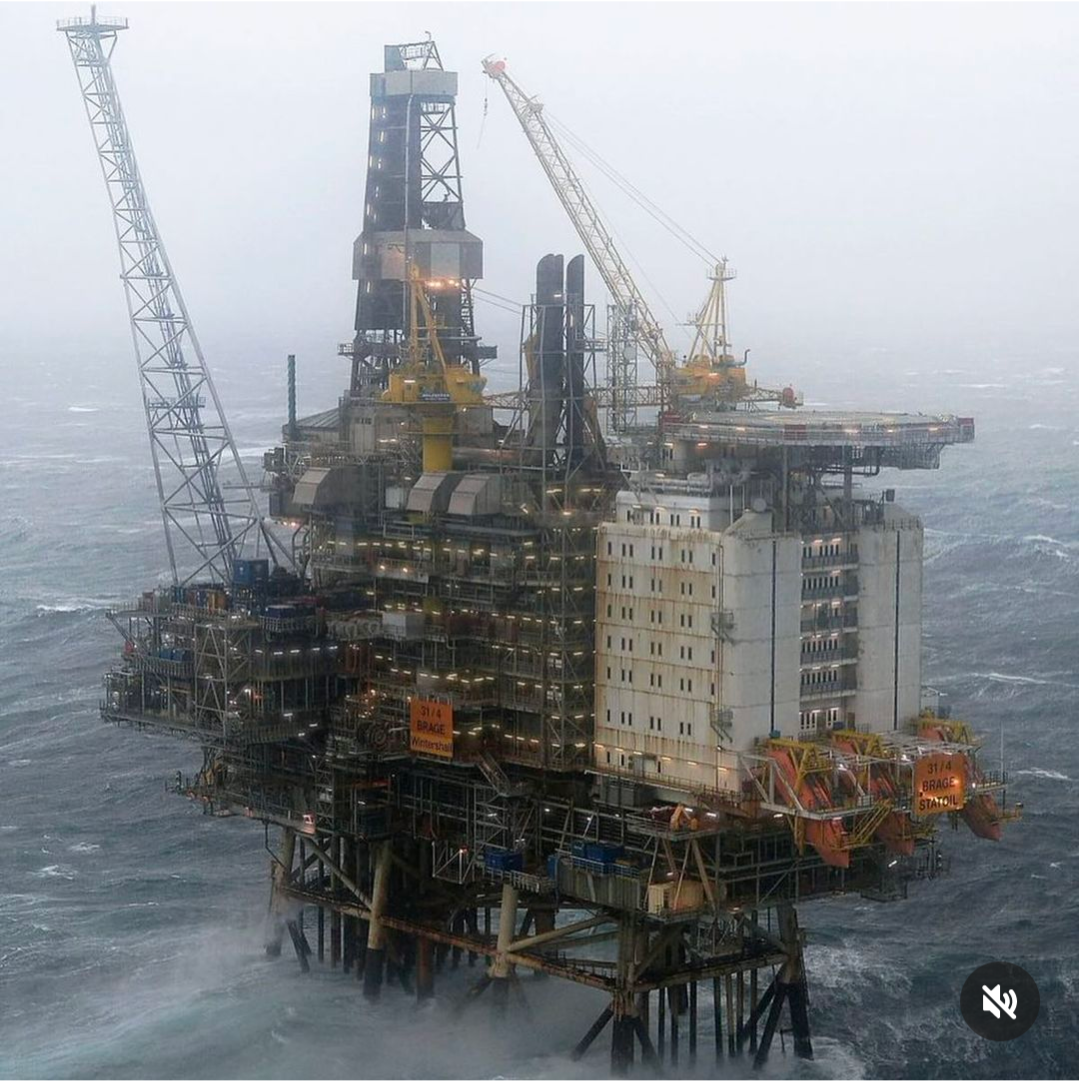

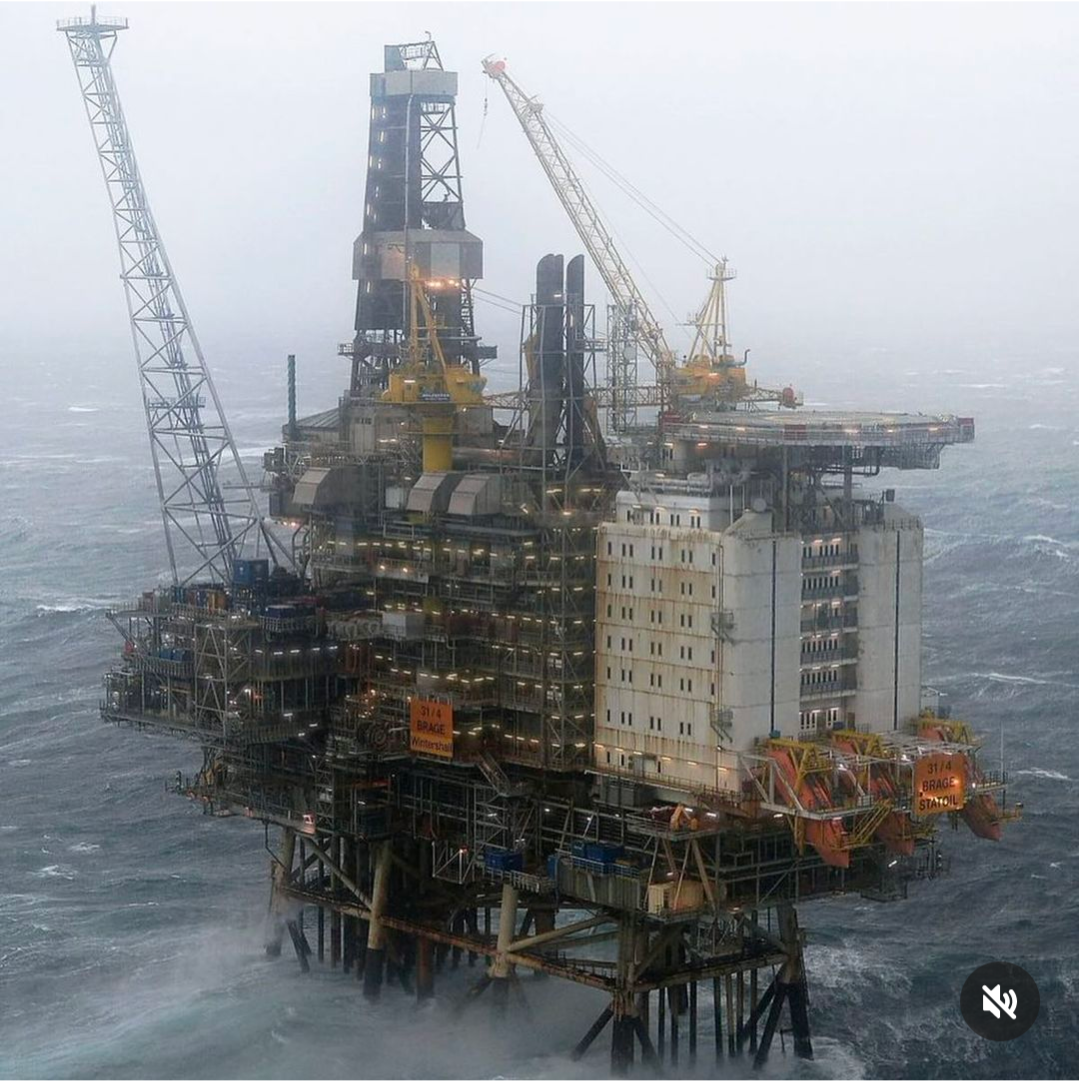

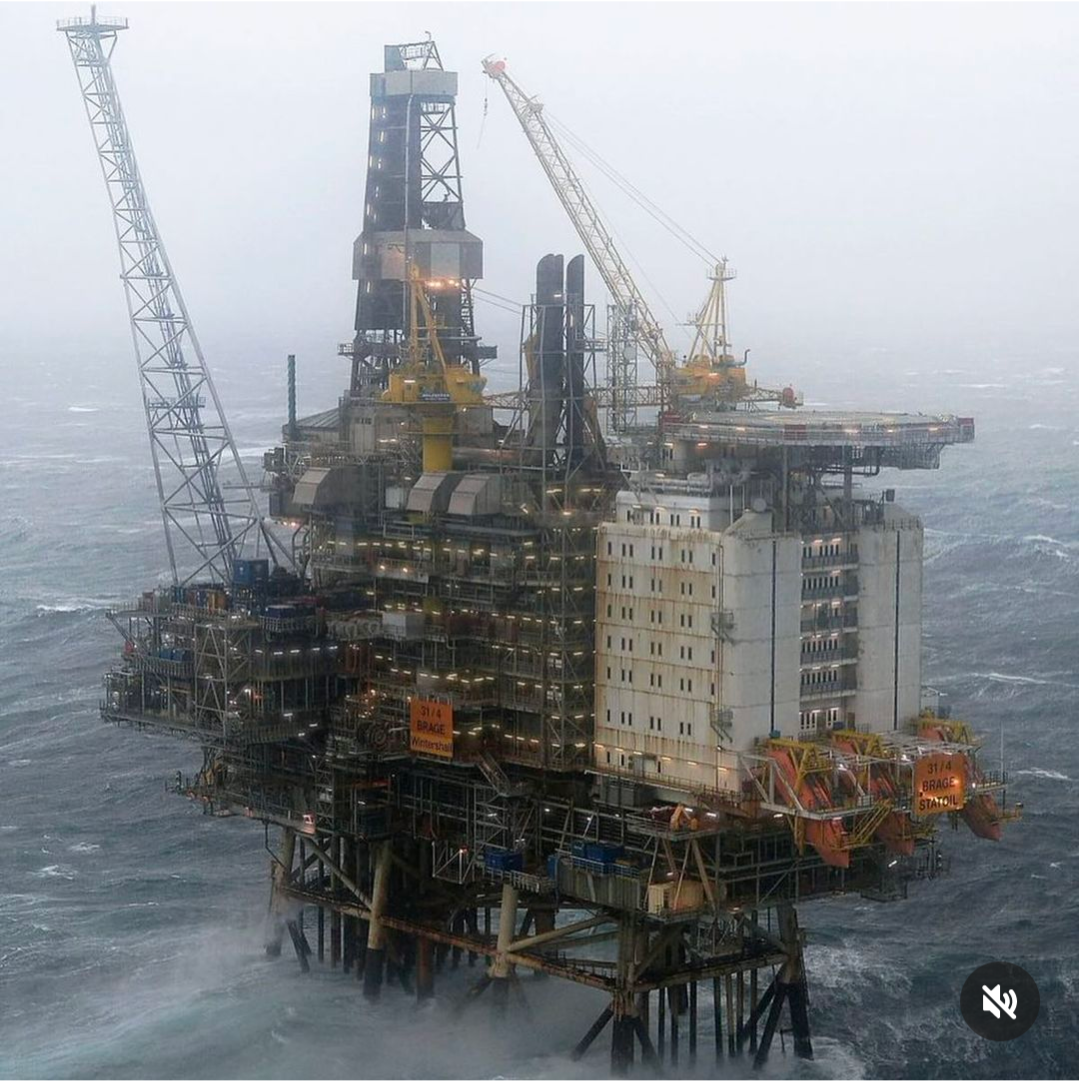

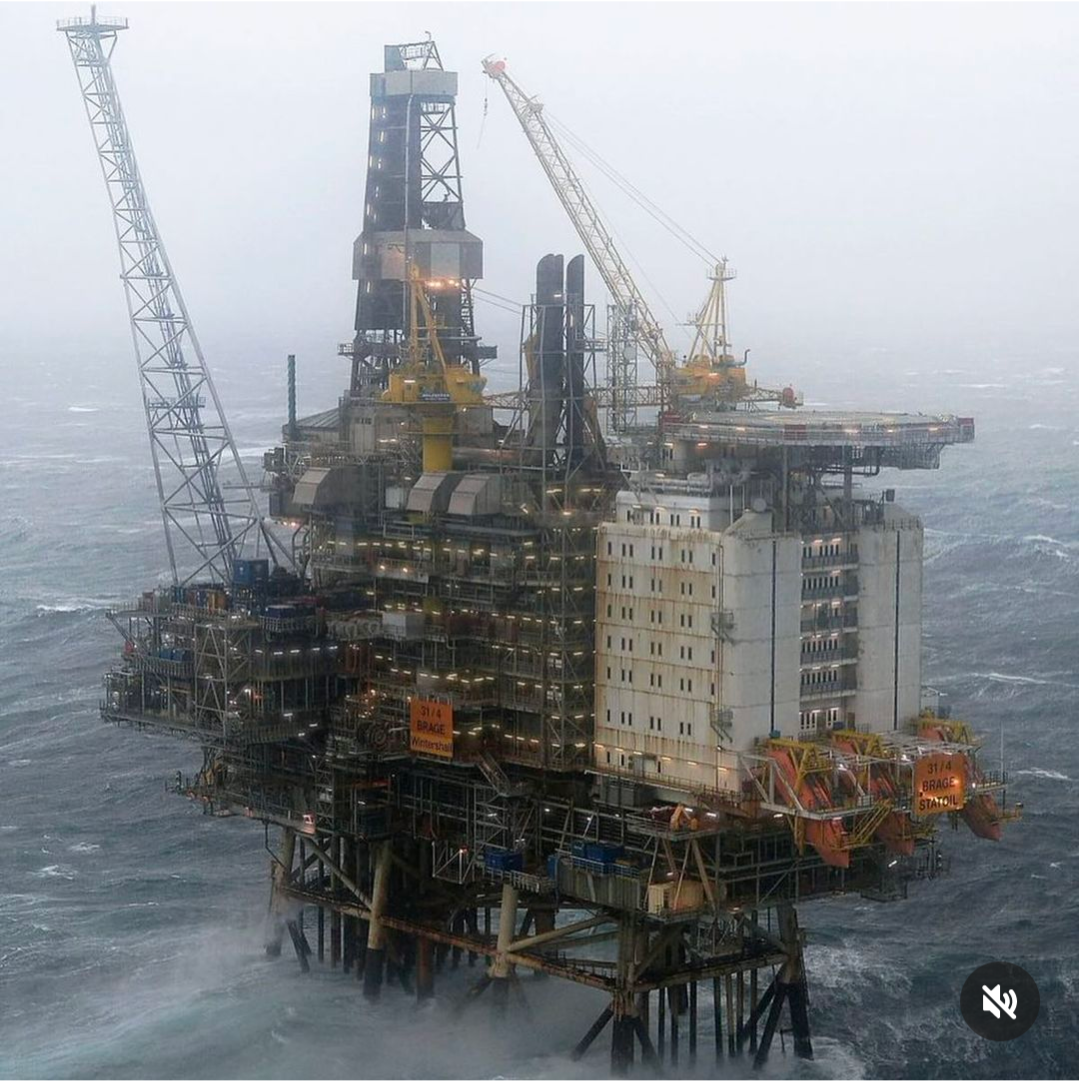

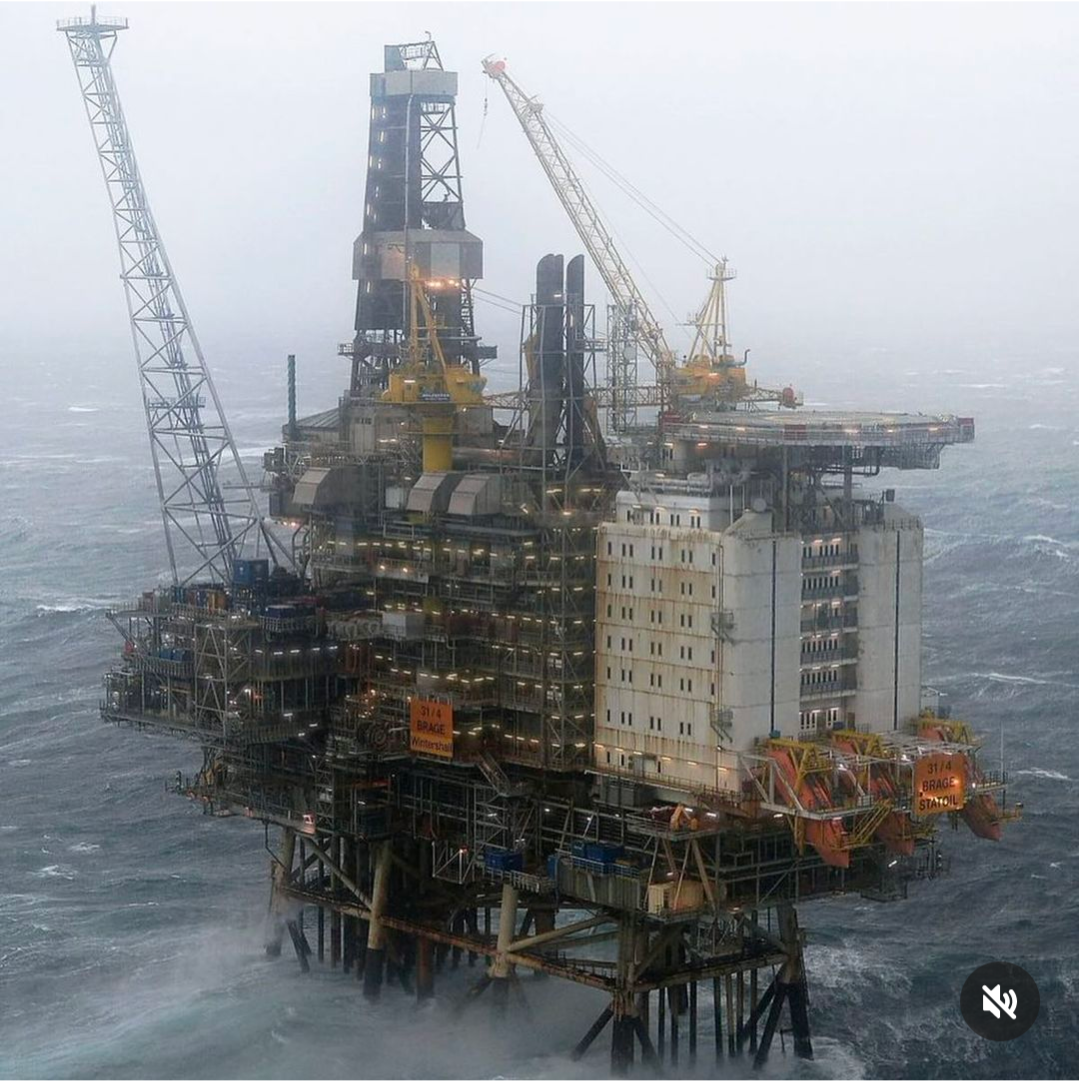

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.

Inspired by Aby Warburg’s titanic visual atlas, – the oldest form of moodboard to date – The Mnemosyne: inside curated moodboards is where we ask artists to walk us through their artistic research with an archive of visual bits (archived images, camera roll pictures, book pages, videos), to contrast algorithmic feeds and restore the fun in personally-curated visual boards.

A few years ago, social media users became suddenly fascinated with mysticism. Personal feeds started disseminating archaic symbols, digital talismans, and grainy religious images. In a piece I wrote back then, I called this phenomenon “Mysticposting”. Maybe there is, after all, something linking our contemporary era to the Middle Ages, a period far more magical, mysterious, and elusive than today’s noisy online world: the need to embrace and become familiar with the chaos and mystery that new technologies bring with them.

The art world usually senses these shifts before anyone else, shaping visual culture long before a motif becomes widely recognised – or turns into a trend. The sculptures of Brooklyn-based artist Brian Oakes are proof of that. Their shiny, hyper-detailed works sit somewhere between seals and mechanical creatures: sublime like a consenting machine, and sacred like a cult object unearthed from a crypt.

To find out more about the relationship between technology, the mysterious, the obscure, and the magical, Brian shared with us their visual references archive, which includes memes, images, screenshots from Instagram, religious symbols, and infographics.

This (above) is a model of a silver and gold mine in the Habsburg Dynasty’s Kunstkammer in Vienna. It is from Kremnica, a town in Slovakia and was made for Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in 1764. The model (known as a handsteine) is made from an assortment of rocks, ores, and silver and were popular gifts from miners to their sovereigns during the 18th century.

(Above) An image from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume basilica dedicated to the life of Mary Magdalene, who, according to the Bible, travelled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and resurrection. The basilica holds many relics, including the alleged aged and blackened skull of Mary Magdalene.

(Above) Alleged Demon trapped in glass from an exorcism in the 17th century in Germany. Supposedly held at the Imperial Treasury in Vienna.

(Above) Picture of a diagram from “S.S.O.T.B.M.E. Revised: An Essay on Magic” by Lionel Snell.

(Above) Screenshot of a 4chan post.

(Above)

Machines are inherently beautiful

Machines should not be mythologised

Sculptures should not and cannot simply reference machines without becoming them.

(Above) I found this tweet at a time when I was thinking about labour that is historically connected to religion, and how to connect it directly to technology in a way that doesn’t feel horribly cheesy or Silicon Valley techno-optimist.

Above is pictured Statoil’s Brage platform in the North Sea, Norway.

Bulldozers and oil rigs resemble sacred elements every day. “Excavation” is too vague a term; “worship”, to me, feels closer to a proper metaphor.