.jpg)

.jpg)

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

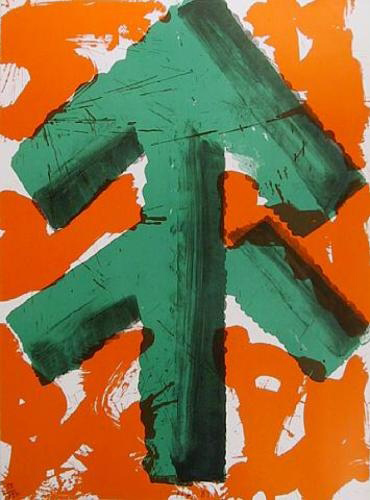

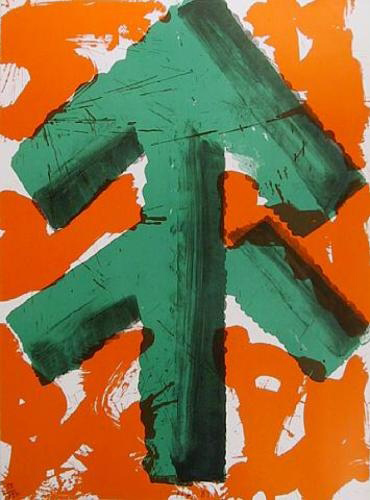

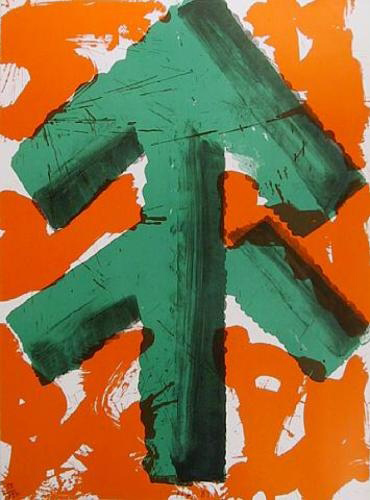

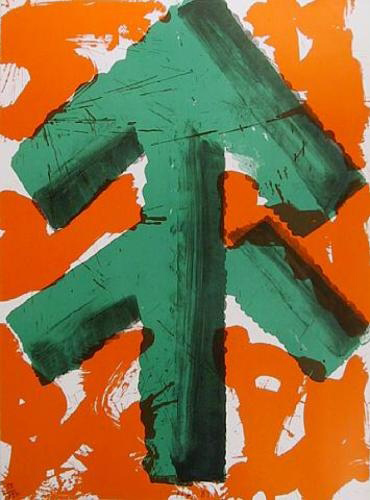

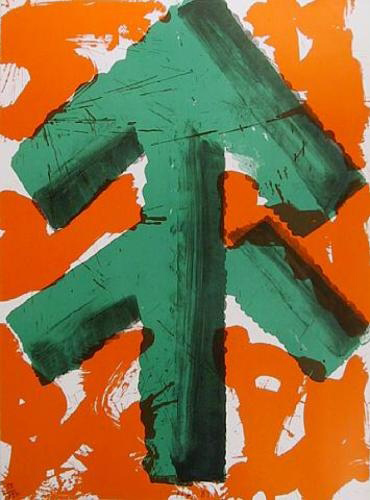

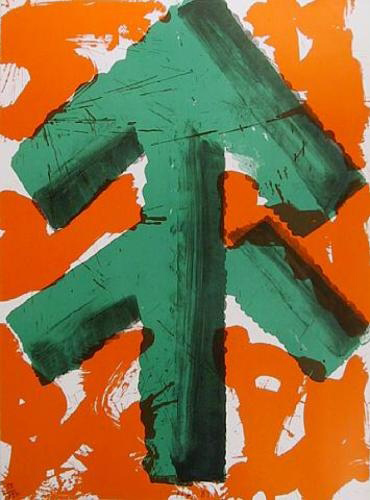

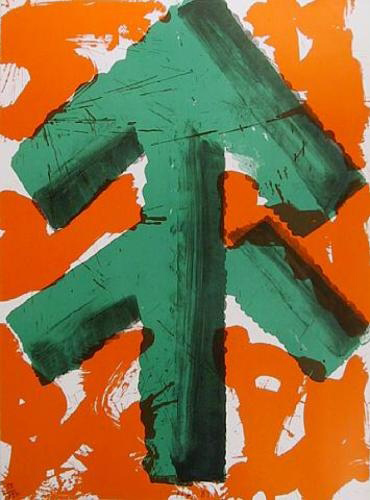

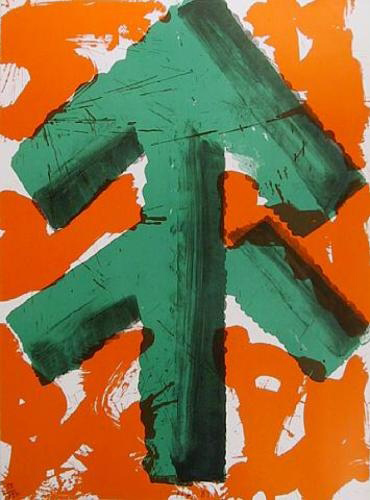

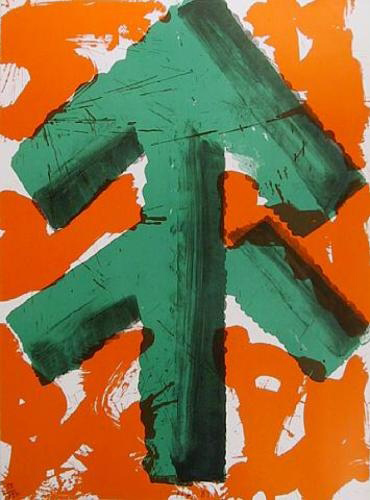

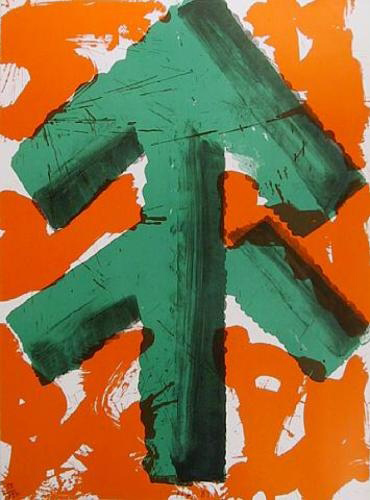

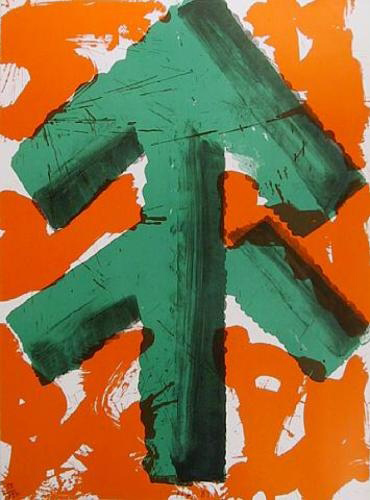

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.

Curation is, of course, a process and act of selection. But overlooking Welcome also risks overlooking the artist’s other connections to these contexts. Although Hodgkin never visited Yugoslavia, the invitation to create work for Sarajevo came indirectly, from fellow artist Andy Warhol. His relationship with the place extends beyond this single print.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) in Skopje holds one edition of Blue Listening Ear (1986) - catalogued as Untitled - which has been displayed in a number of collection exhibitions over the last decade. It shares its framed form with many of Hodgkin’s views from Venice, which stand out in Pitzhanger’s Main Gallery of Hodgkin’s prints; in his studio, with the oil painting Black as Egypt’s Night (2005-2013), an incidental connection to Skopje’s strong representation of artists from the SWANA region.

Such questions matter materially. In a Public Garden (1997-1998) - the very work from which the exhibition takes its title - was executed through a complex process of lift-ground etching and aquatint, with carborundum and hand-colouring in acrylic paint, on hand-made Somerset paper. These were practices tested in Blue Listening Ear, one of the first prints that Hodgkin made with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in London, which brought him to experiment with printmaking: ‘…Jack introduced me to the delights of carborundum, its ups and downs, in fact. It’s a hard substance that’s ground down and mixed into a paste. When it’s painted onto the printing plate, it makes a hill, which forces a valley into the surface of the paper. I’ve used it a lot to give relief to the surface.’

In the hierarchy of forms, prints are often undervalued, although the planning and process can take as much time as those of other mediums. For instance, there is still no dedicated print curator at Tate, which holds one of Hodgkin’s early paintings of a hotel garden, from 1974, alongside other works. The exhibition at Pitzhanger, more positively, begins with and highlights a good selection of these works, and visitors can purchase lower-cost editions of Hodgkin’s prints at the gift shop on exit.

.jpg)

Paying close attention to the medium exposes other overlooked lines of enquiry. Mango (1990-1991) is represented, but what of the Little Lotus (1978) and Mango (1978) that currently hang in the artist’s studio-as-gallery made of natural vegetable dyes, or other works rendered on khadi paper? Moreover, how did Hodgkin’s works enter this collection, formed through donation and solidarity, and where are the records or communications with the artist? An online search of ‘Howard Hodgkin Yugoslavia’ first links to the Yugoslav Wars, listed under other events that happened in 1992 in the artist’s profile at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Though dominant, this is not an accurate representation of the region, nor the artist’s relations with it.

The act of felling may sometimes be unintentional, but it is never silent, and someone, somewhere, is very likely listening, if not for the fall, then its reverberations through time, space, and societies.

Howard Hodgkin: In a Public Garden is on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing until 8 March 2026, and travels to the Lightbox in Woking in 2026.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This question, a thought experiment which considers whether ‘sound’ requires a conscious observer to exist, is often posed beyond the realms of philosophy, notably in the fields of the environmental sciences and ecological thinking. It can also be asked of In a Public Garden, the largest institutional exhibition of prints by Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017), currently on view at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in Ealing, which has overlooked (or felled) a notable work from the artist’s practice.

The trees represented here are those found in India, both natural and man-made. In 1992, Hodgkin collaborated with the Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on a large mural for the entrance of Correa’s building for the British Council in New Delhi, a five-storey design which functioned as a library, auditorium, and art gallery. A maquette for the mural in the exhibition suggests how Hodgkin was inspired by the form of a large banyan tree, or rather its shadow swaying in the breeze. Some of his preparatory brush drawings for the branches are displayed in a vitrine.

.jpg)

The mural was made of black Katappa stone and white Makrana marble tiles, recalling a technique used in Mughal architecture. This selection is illustrated in the exhibition in a series of archive photographs, including one of the artist pointing in rejection at some stone samples proposed for the frame of his mural on the building’s exterior façade. It’s a subtle connection to the architect Sir John Soane, who constructed the English country house of Pitzhanger prior to his best-known Museum in central London, almost neighbouring Hodgkin’s studio, and the British Museum, in Bloomsbury.

Long before the 1990s, Hodgkin frequently visited the Indian subcontinent and collected large numbers of miniatures, eventually assembling an outstanding collection of paintings and drawings from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. He often incorporated elements of their designs in his works. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue for Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now (2023), which included Hodgkin’s work alongside contemporaries and friends like Bhupen Khakar, curator Hammad Nasar suggests this is most notably in his use of horizontal bands of colour; it can also be observed in the way Hodgkin ‘framed’ his own works in paint.

.jpg)

A delicate Mughal drawing of an elephant, rendered in black ink and heightened with white and gold, raises an important point about care. In his lifetime, Hodgkin presented three paintings to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford; the latest, of An Elephant in Mast (c.1700), was represented in Beyond the Page. As many miniatures were already on long-term loan to the Ashmolean, Hodgkin had hoped that the museum would acquire his entire collection of 122 Indian paintings after his death. A lack of clear and verifiable ‘provenance’ information (or ownership histories) for one-third of the works, however, led the museum to reject this ‘very generous purchase offer’ from the artist’s estate.

These 38 works are now loaned to the Ashmolean, but remain in the ownership of the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust. The Met acquired the outstanding 84, many of which were displayed in an exhibition in New York in 2024. (We might speculate whether Shanay Jhaveri of the Barbican in London, formerly the Met’s first curator of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, with responsibility for collection building, had some involvement.) A late-17th-century watercolour of a Mughal ruler riding his prize elephant in their collection certainly relates to the drawing on display here.

Swimming (2011), a poster print for the London 2012 Olympic Games, could be passed by, as it is awarded pride of place in the Manor Basement. It is curious why curator Richard Calvocoressi, who started the exhibition almost exclusively with prints, opted for this rather than Welcome (also called Winter Sports, from the Art and Sport series) (1983), the poster Hodgkin designed for the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The bold, dichromatic print centres on a jungle green chevron, which looks remarkably like an abstracted tree. It could also represent an arrow, which became a recurrent motif in Hodgkin’s prints from the mid-1980s, as the artist simultaneously shifted towards more poster-like images and away from borders or frames.

Importantly, Welcome is a rare example of the artist’s work in a series. ‘Every painting was a one-off,’ remarked Anthony Peattie, a writer and Hodgkin’s partner, in conversation at the artist’s former studio, an urban glasshouse with a garden of its own, ‘so no single work is representative’. This raises interesting questions concerning the artist’s relations with and between the mediums of painting and print, the latter an inherently reproducible medium.