Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

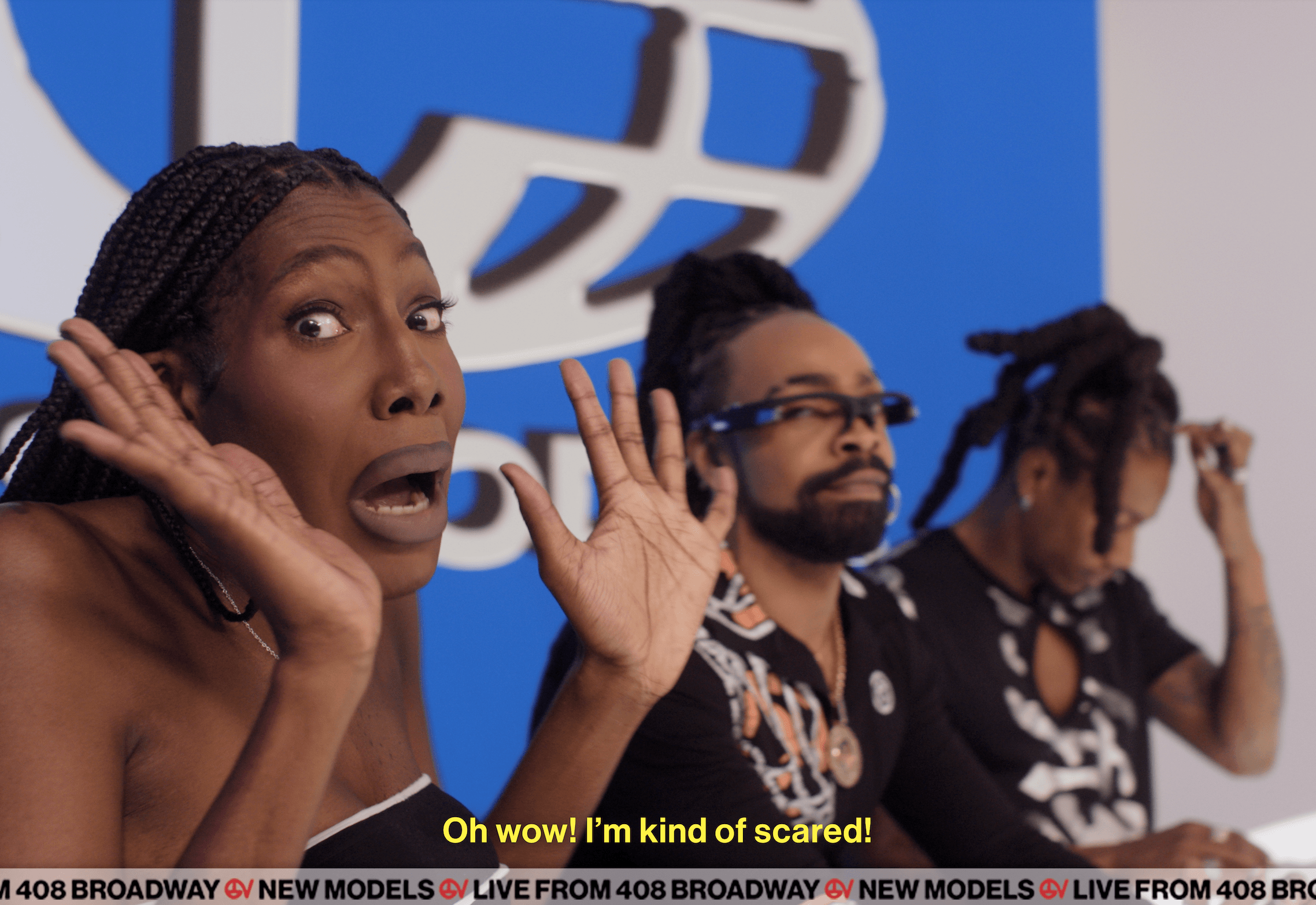

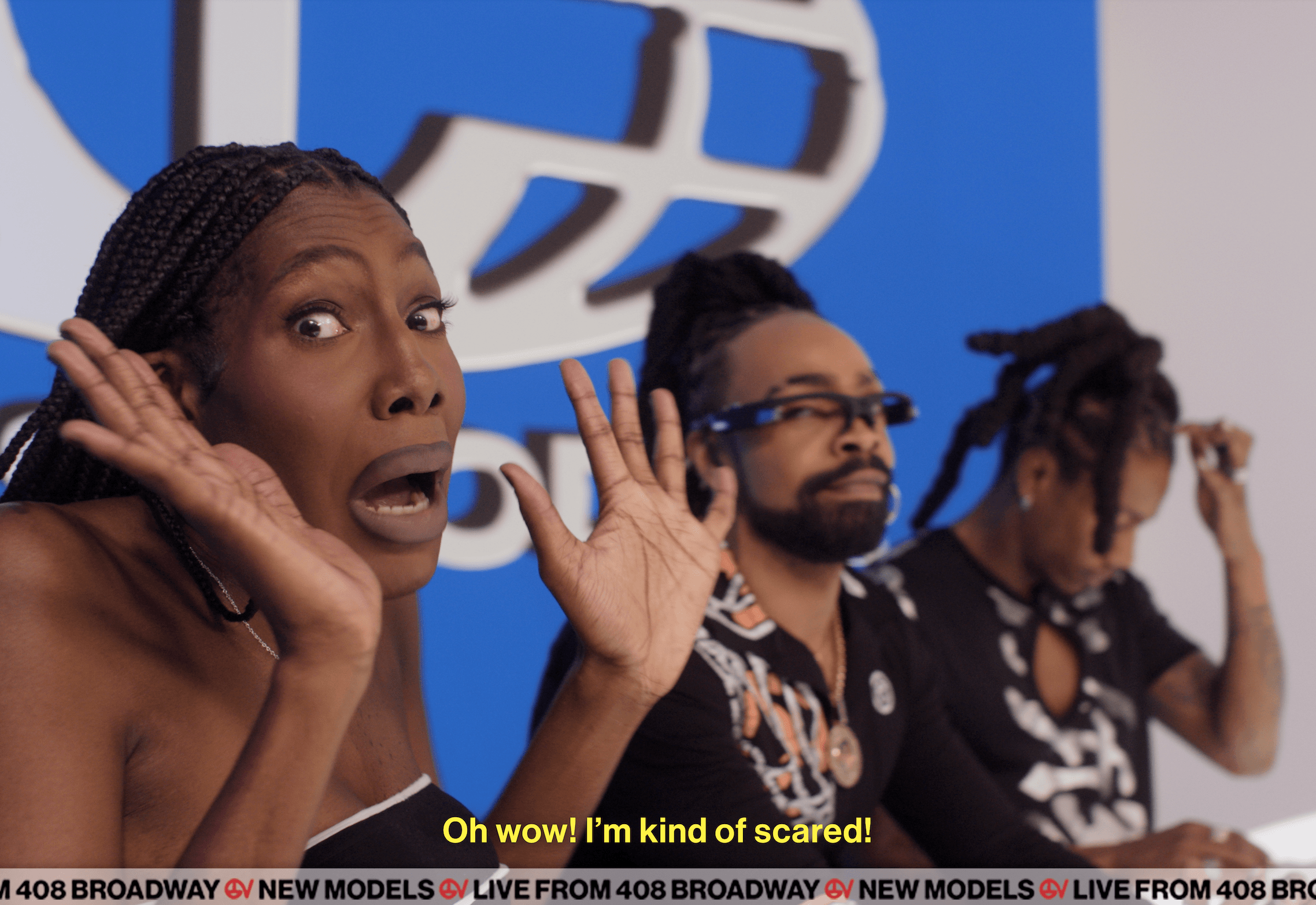

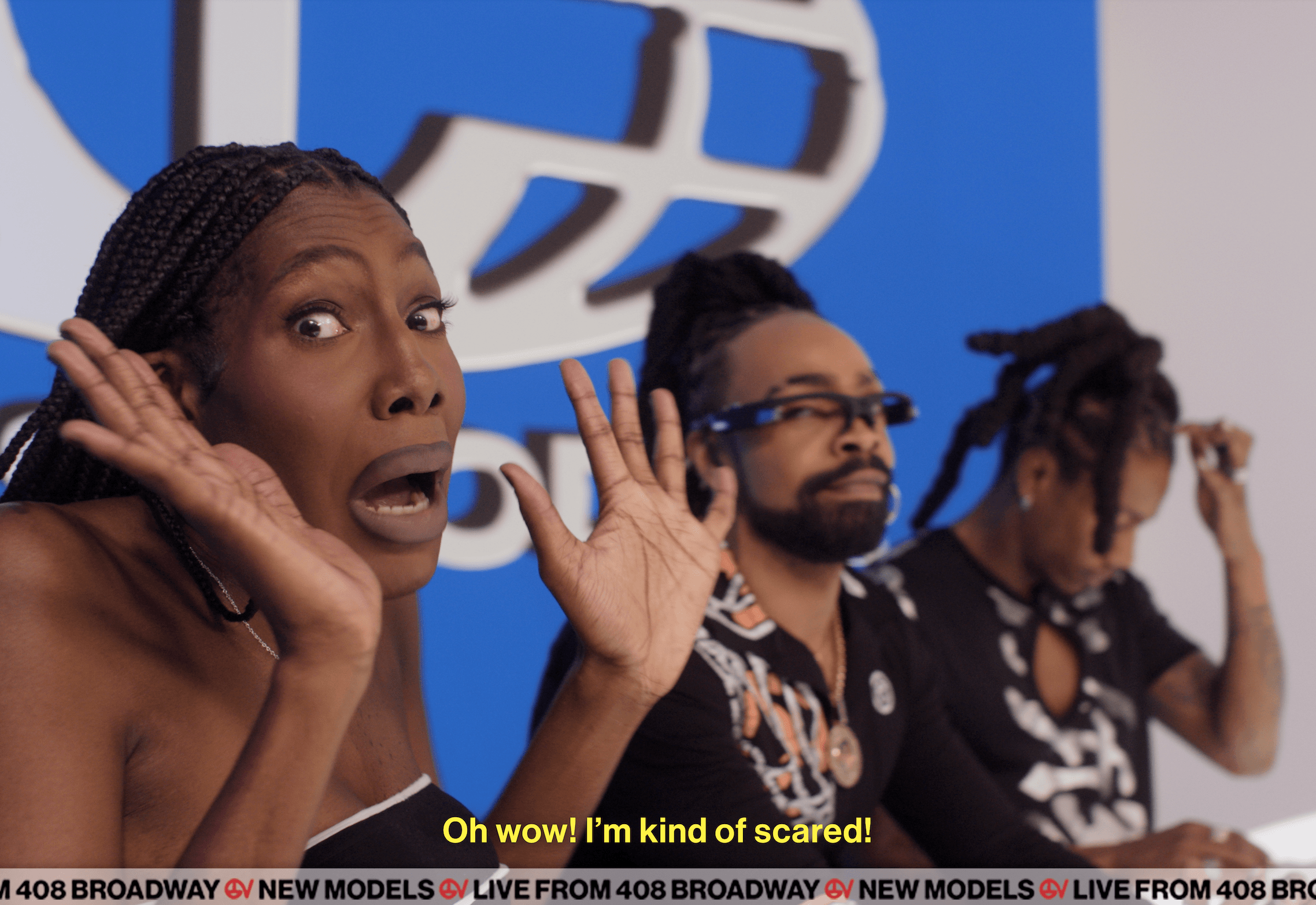

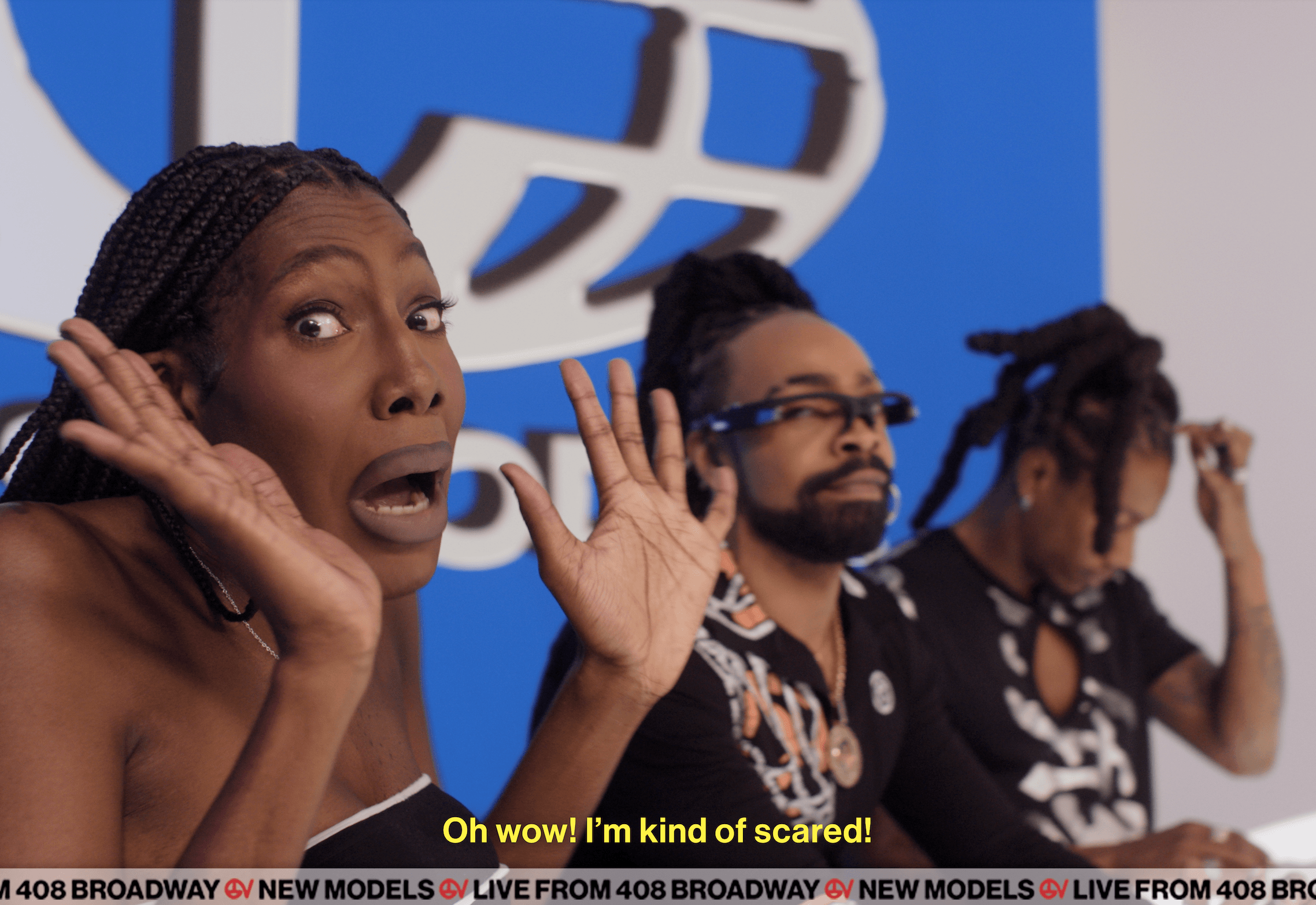

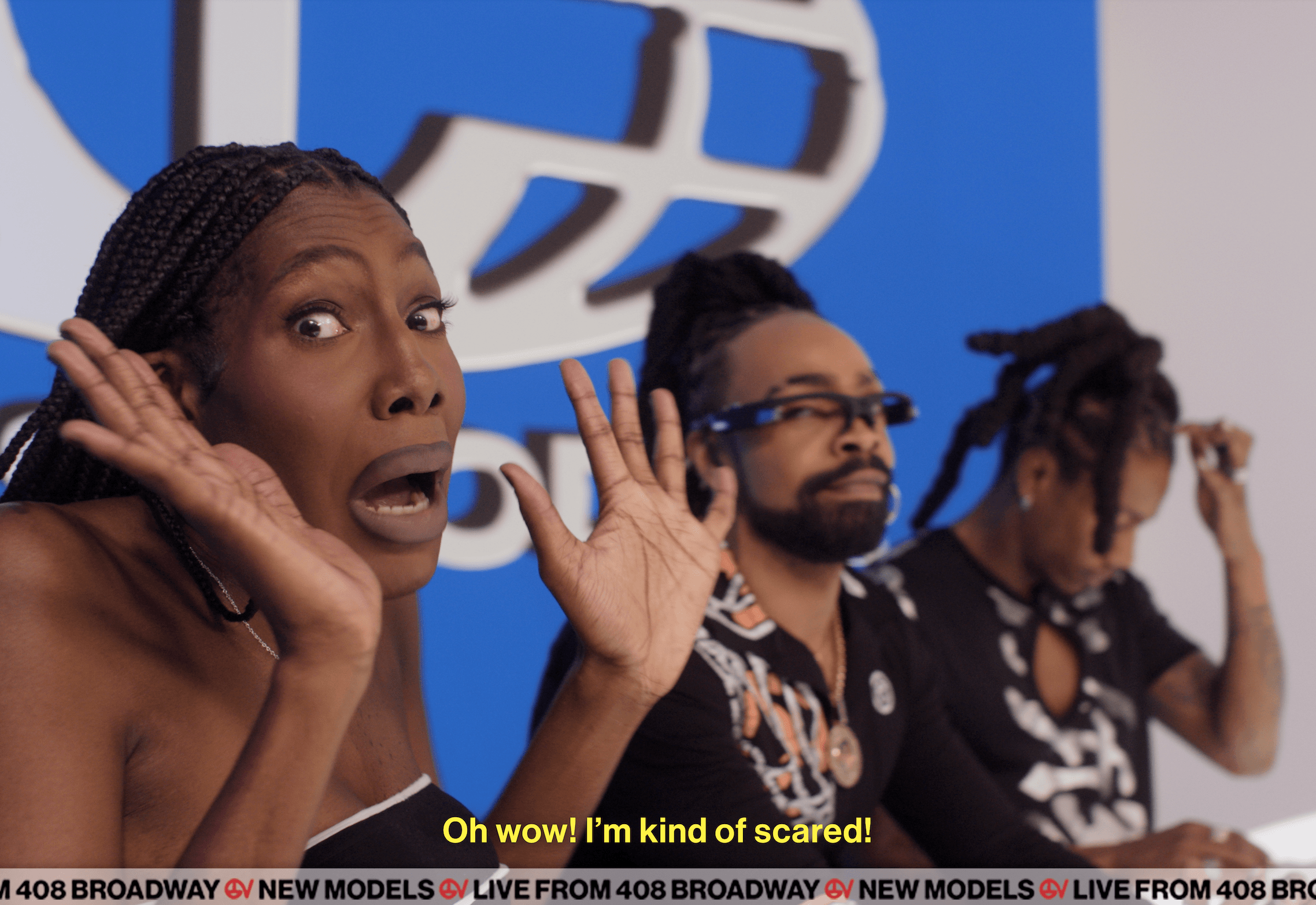

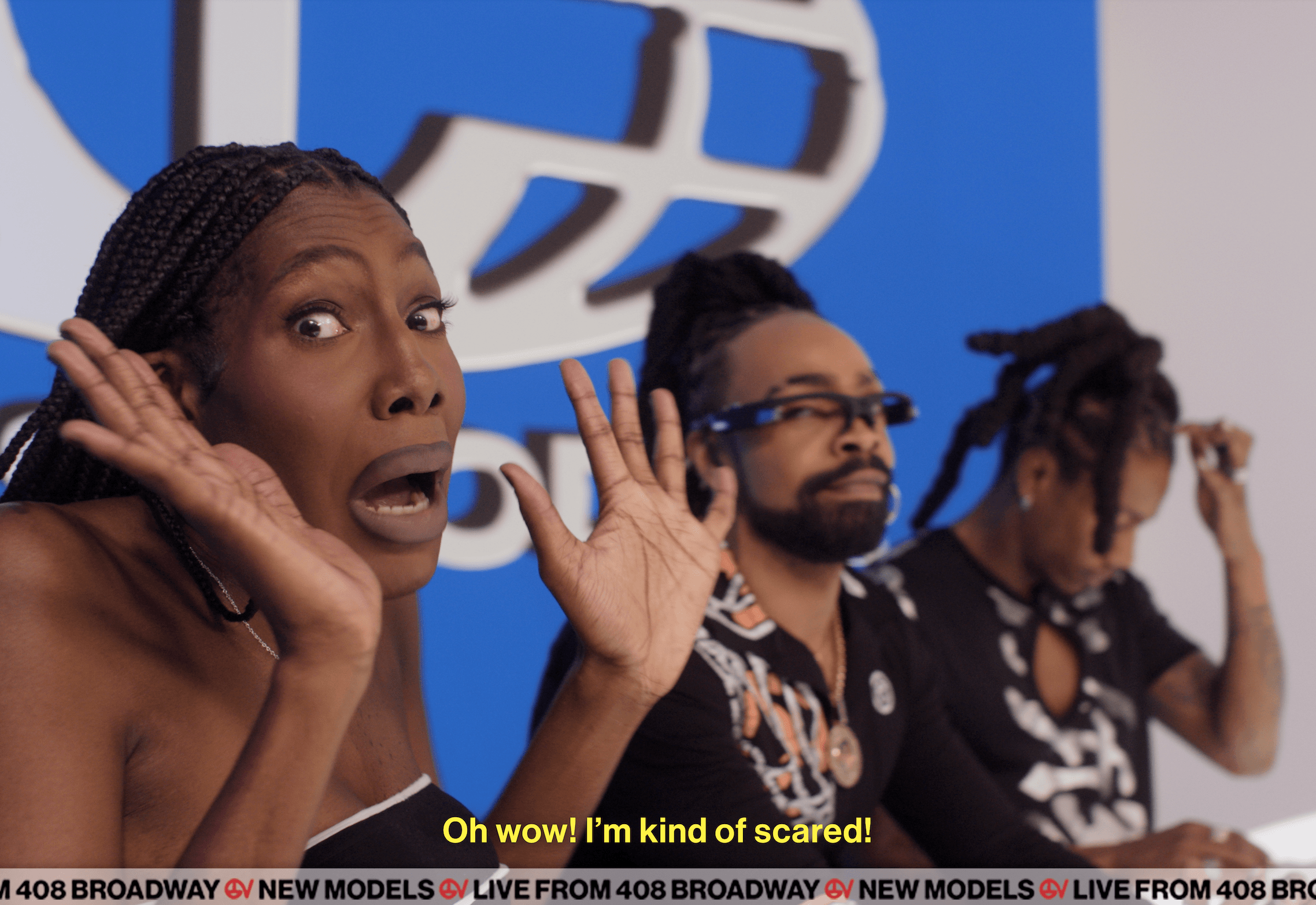

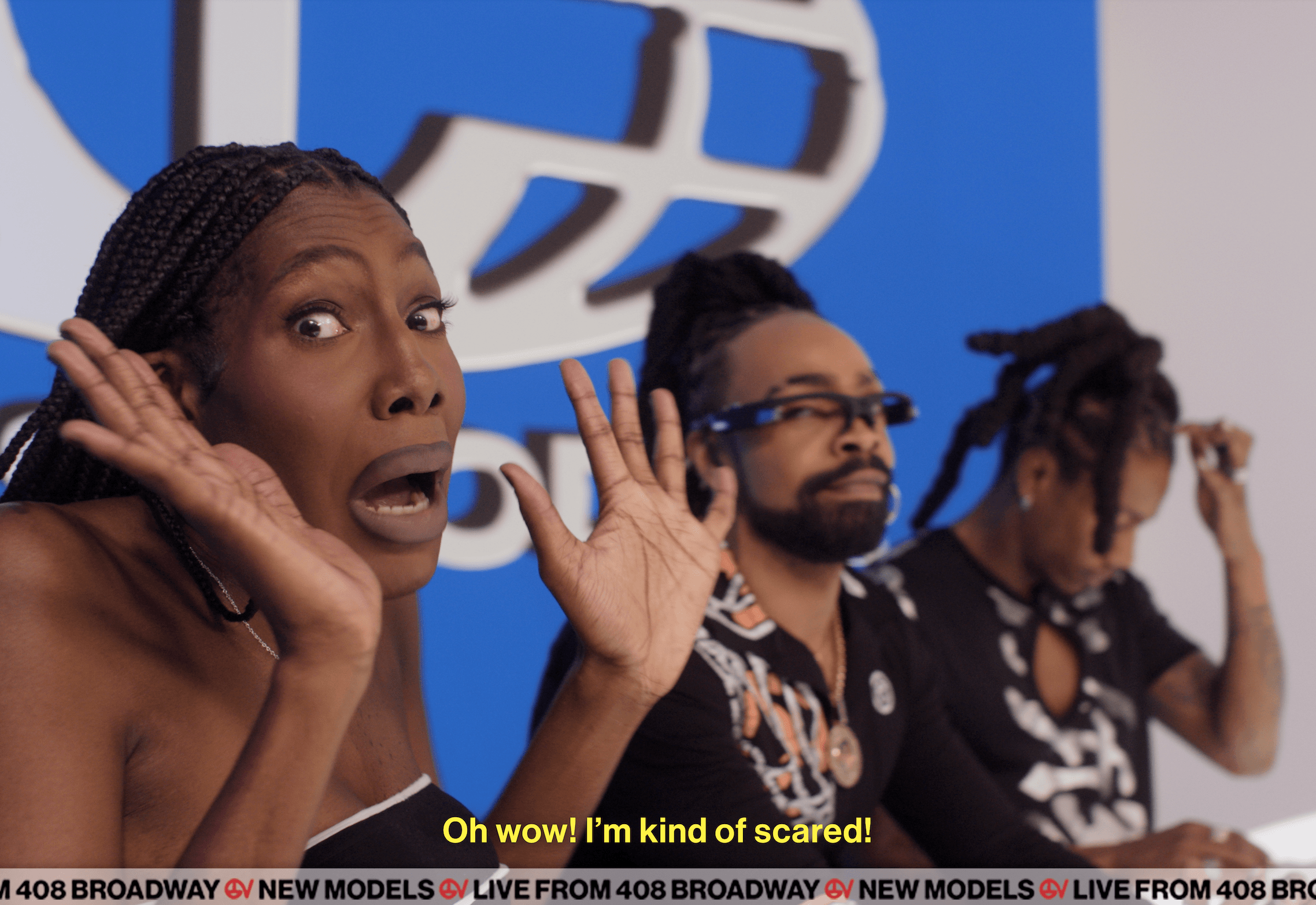

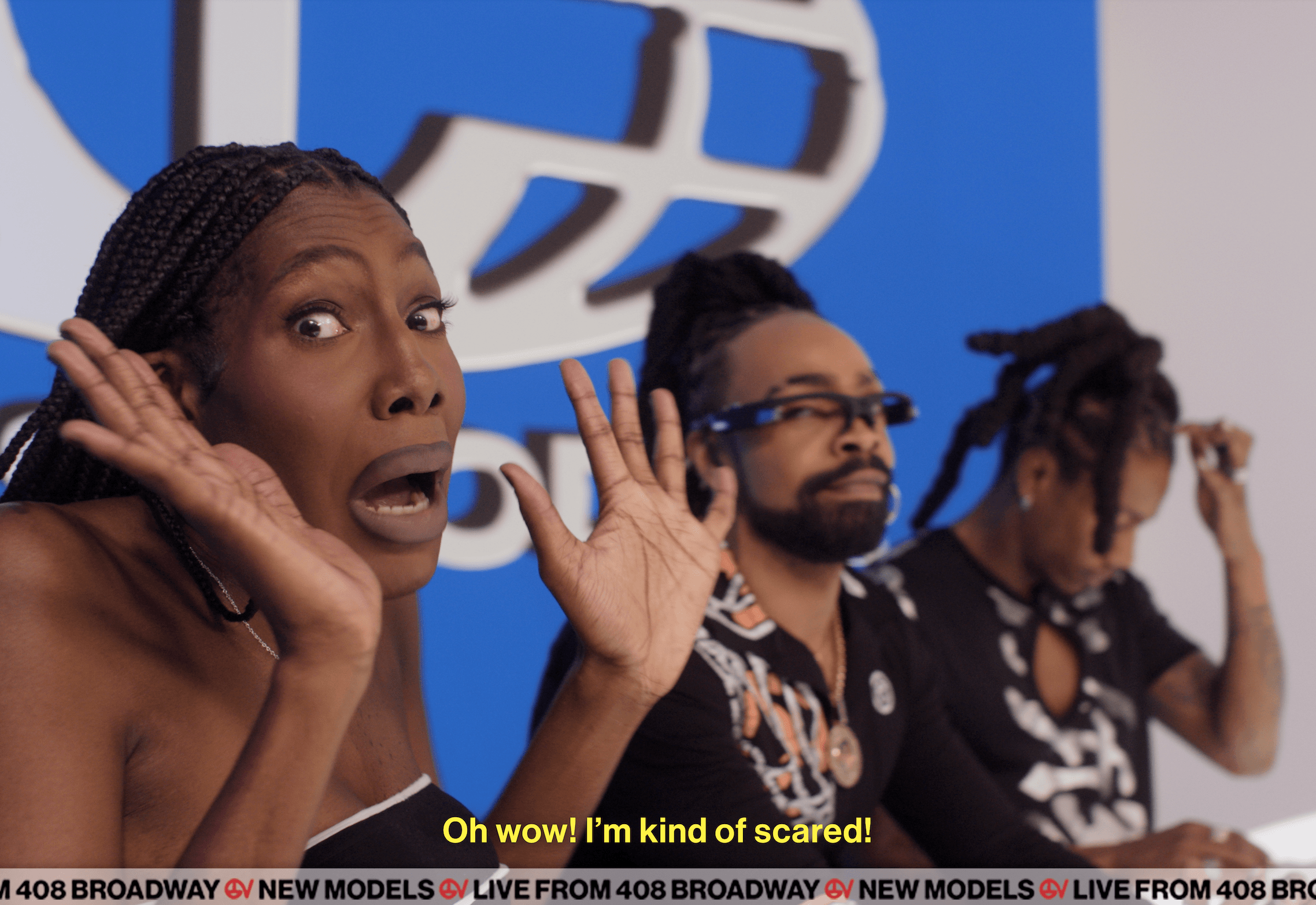

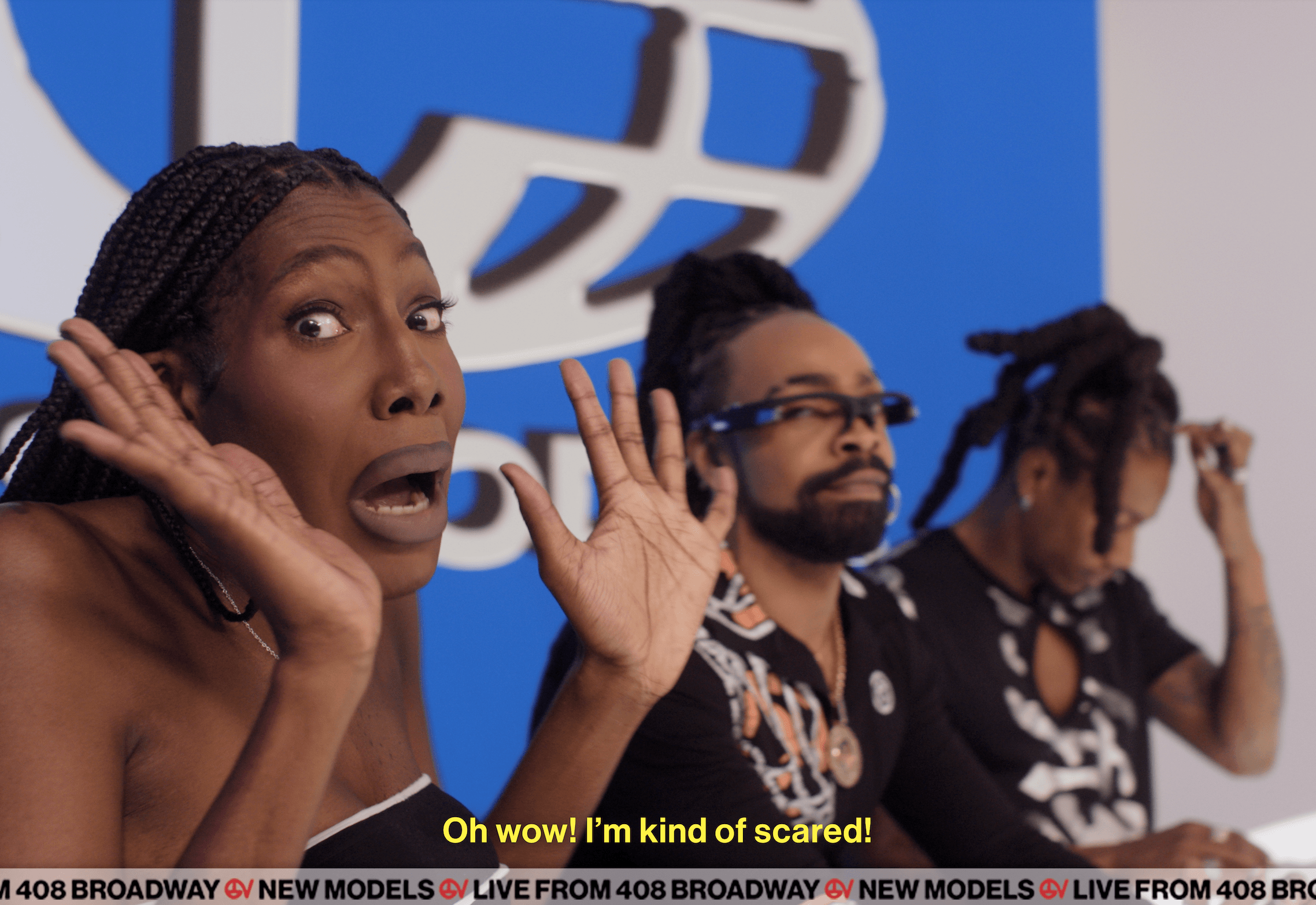

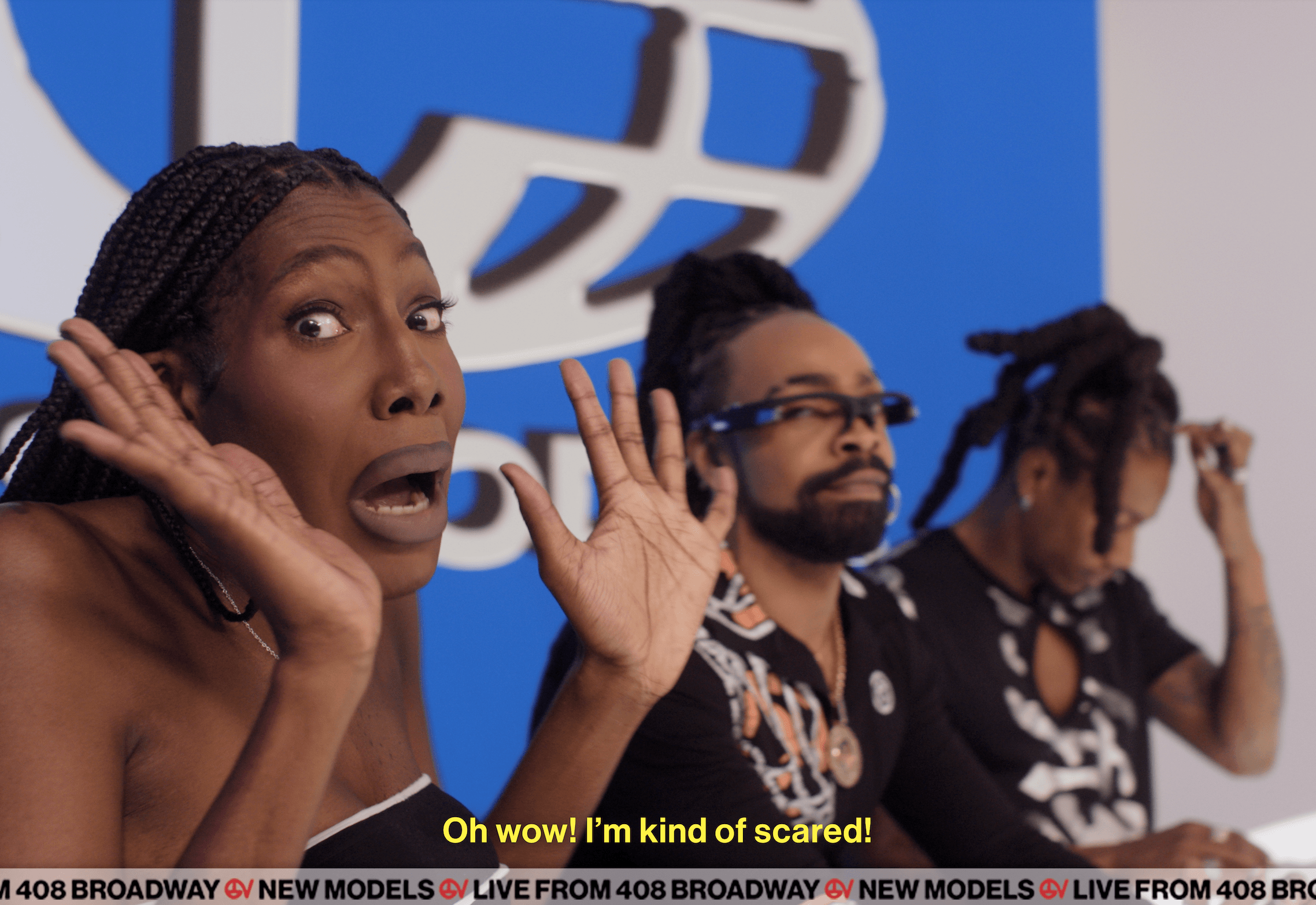

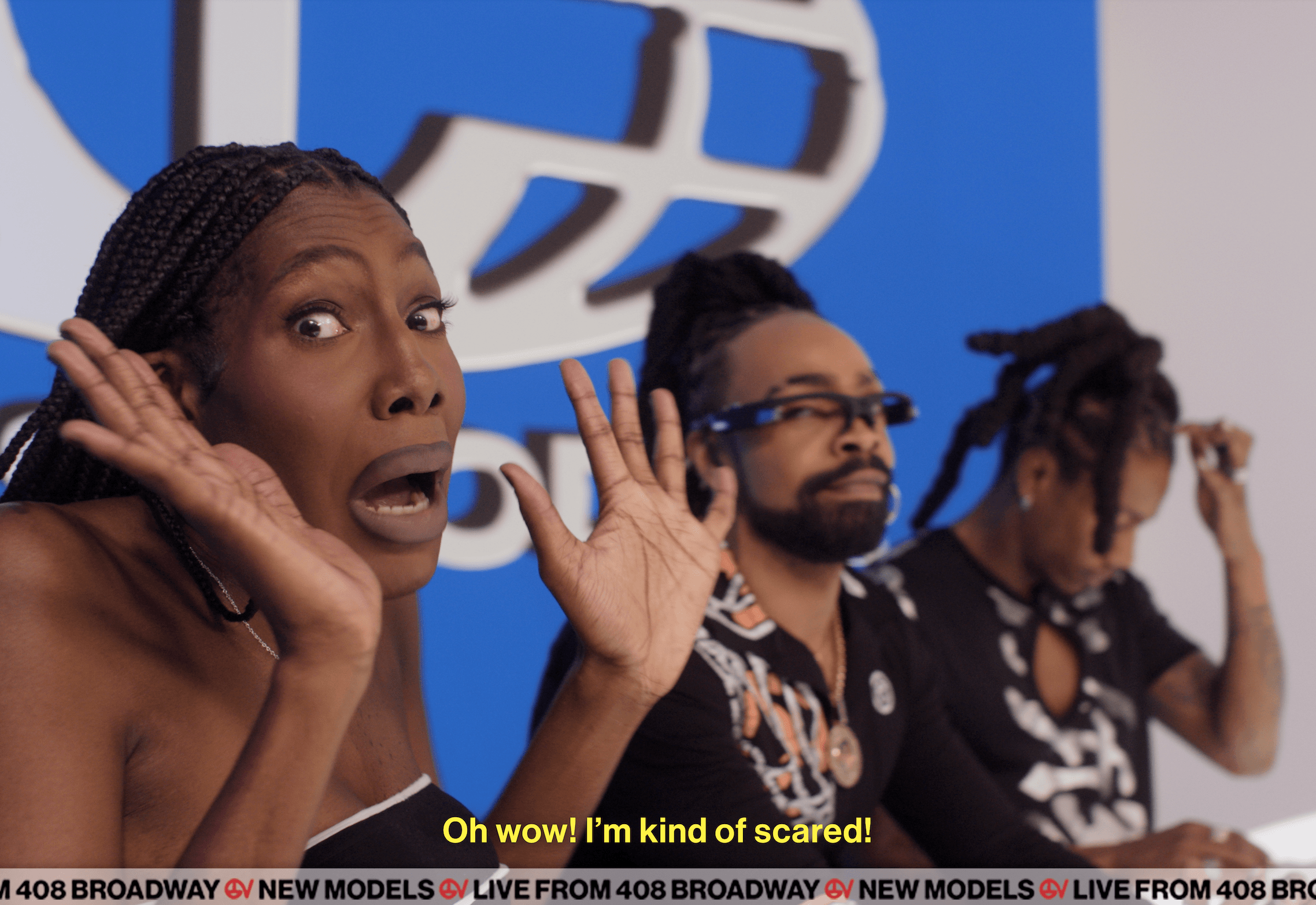

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.

Just off Surrey Street, a new exhibition titled Paradigm Shift unfolds in the subterranean spaces beneath 180 The Strand. 180 Studios, in partnership with Ray-Ban Meta, presents an ambitious moving image show curated by Jefferson Hack and Mark Wadhwa, with a thoughtful catalogue written by associate curator Susanna Davies-Crook. Featuring both newly commissioned and sourced works from the 1970s to today, the films span a range of genres and industries, including gaming, fashion, music and avant-garde cinema.

Over the past five decades, our relationship with screens has changed dramatically. Our consumption of moving images is at an all-time high, from the unprecedented access provided by streaming platforms to the Instagram reels we binge during brain-rot sessions. These shifts mirror changes in our attention spans. Nowadays, not even the cinema offers deliverance from the glow of a smartphone screen in the dark. Paradigm Shift pulls us away from binge-watching and doomscrolling (which often occur simultaneously), and instead requires active engagement rather than passive absorption.

The exhibition space itself demands full attention. With no phone signal or windows, the underground maze-like setting shuts out external distractions. In a dimly lit concrete room, Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1991) plays above a tower of speakers. The montage of archival footage charts British subcultures and dance scenes from the 1970s to the 1990s. Twenty-somethings dance freely, neckties fastened around their foreheads like homemade crowns—self-appointed rave royalty. The editing, paired with the booming techno and strobe lighting, makes the room feel like an extension of the film itself.

On the other side of a dark corridor, Pipilotti Rist’s iconic Ever Is Over All (1997) is projected across two adjacent walls. The audiovisual installation contrasts a woman joyfully smashing car windows with a red flower as she frolics down a pavement, with dreamy close-ups of flowers in a field. The two scenes bleed into one another, femininity and rage coincide in the corner of the room. The highly saturated primary colours mirror the red-splattered rug and blue foam seating where visitors are sprawled across, watching in awe.

Gillian Wearing’s 25-minute film Dancing in Peckham (1994) captures the mixed reactions of bystanders as she records herself dancing in the middle of a shopping arcade without any music. The social contract has since changed, and now, in 2025, it is hard to walk through London without becoming an extra in someone’s TikTok. Echoes of viral audio clips drift through the candy-coloured streets of Notting Hill.

I manage around 15 minutes of Ryan Trecartin’s 108-minute fever dream of a film, I-Be Area (2007), before I start to feel a bit lopsided. It defies interpretation and doesn’t seem to care. In the next space, a mirrored room hosts Telfar TV, New Models 3 (2025), an experimental reality show commissioned by 180 Studios from the cult fashion label. Blending mockumentary with parody news channel, the piece documents the Telfar New Models casting event and expands into a sharp critique of representation and racial capitalism.

The exhibition does not progress in chronological order, and there is a lot to take in, both in volume and substance. Arthur Jafa’s powerful APEX (2013), a rapid-fire slideshow of 841 still and moving images set to an anxiety-inducing beat, is overwhelming and sobering. Four screens playing various films from Derek Jarman’s Super 8 Shorts (1973-1976) series face each other around an X-shaped sofa. The scenes are varied. Some hypnotic, others more difficult to watch. One is a voyeuristic black-and-white time-lapse of Jarman’s loft, I feel as if I am peering through the glass of a zoo enclosure.

By the time I reach Sophia Al Maria’s Tiger Strike Red (2022), a biting exploration of colonial legacies in Western museums, my mind feels overclocked. Paradigm Shift concludes with Andy Warhol’s television series Fashion TV (1979–1980). A collage of catwalk shows and interviews with nightlife moguls creates a dazzling portrait of New York’s fashion scene at the turn of the decade.

Paradigm Shift offers a wonderful overview of the twists and turns that moving image art has taken over the last few decades, and makes some guesses as to where it might be heading. I feel inundated with visuals and ideas to sift through as I walk back up the stairs to ground level. As I push open the door onto Surrey Street, it takes a moment for my eyes to adjust to the daylight. I’m hit with the realisation that, in the grand scheme of art, moving image is relatively new—our advancements mere baby steps compared to what lies ahead, especially at the rate at which technology is developing. You know what they say: we’re always just one epiphany away from a paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift presented by 180 Studios is on from 14 October until 31 December 2025.