Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

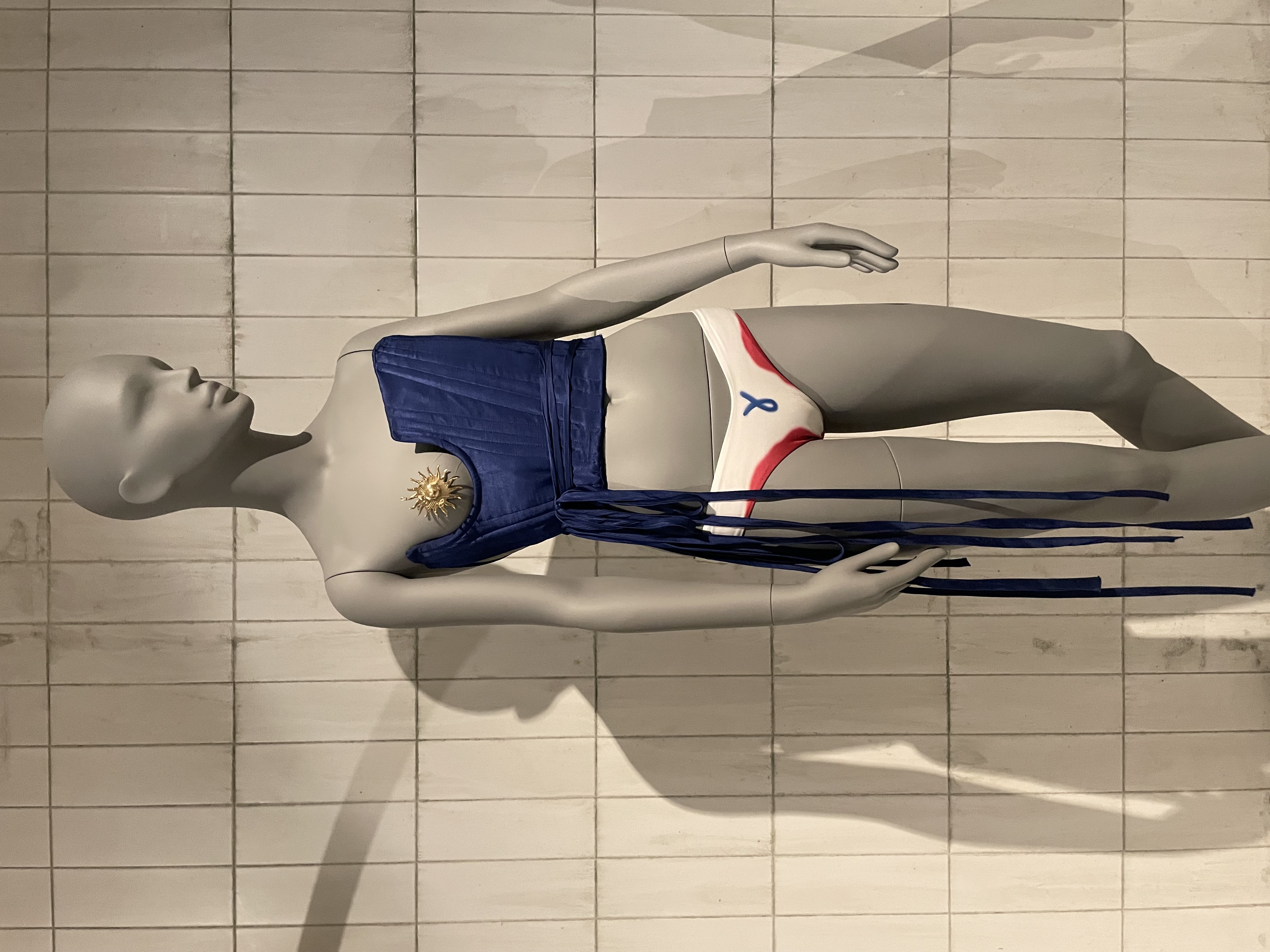

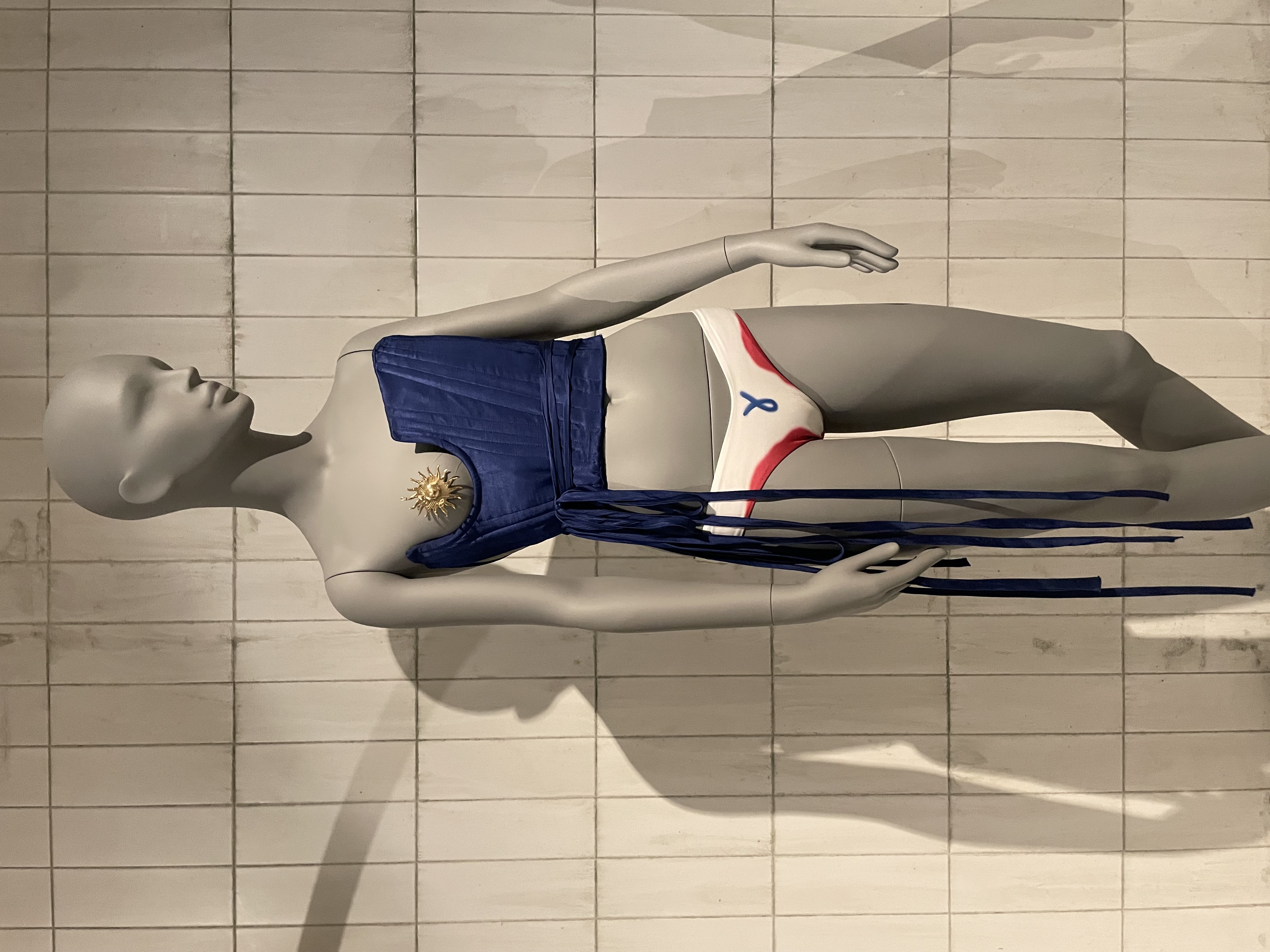

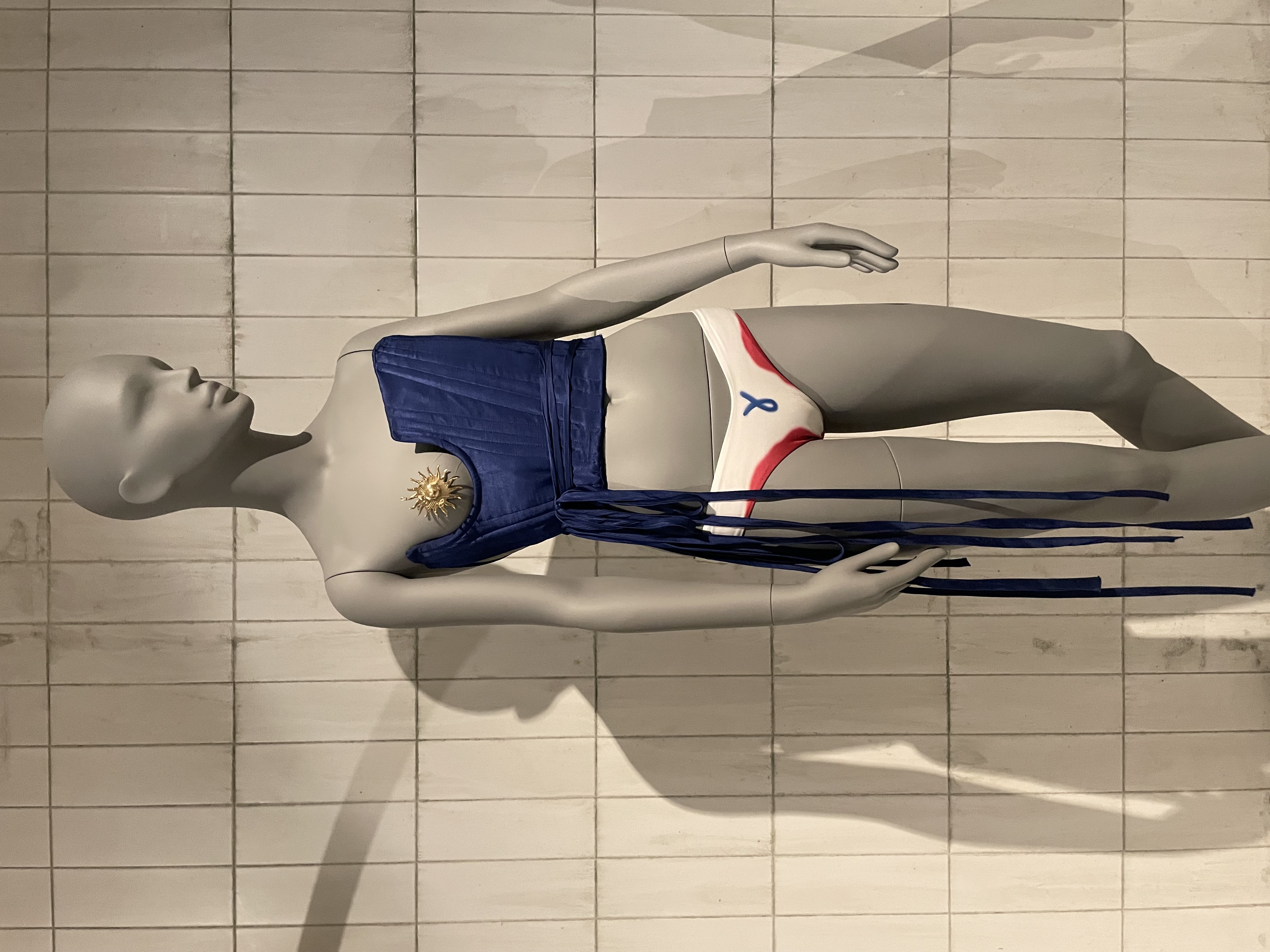

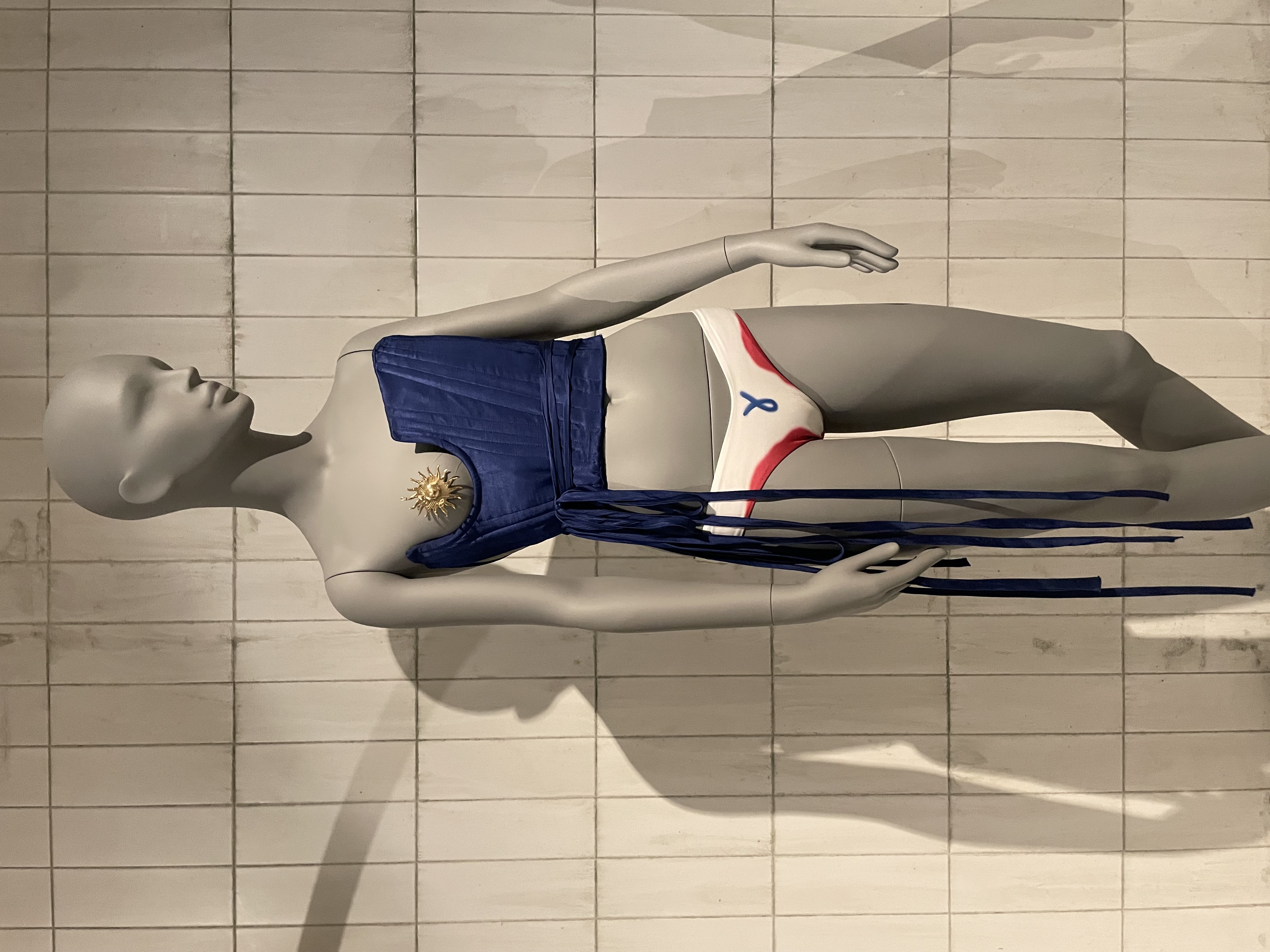

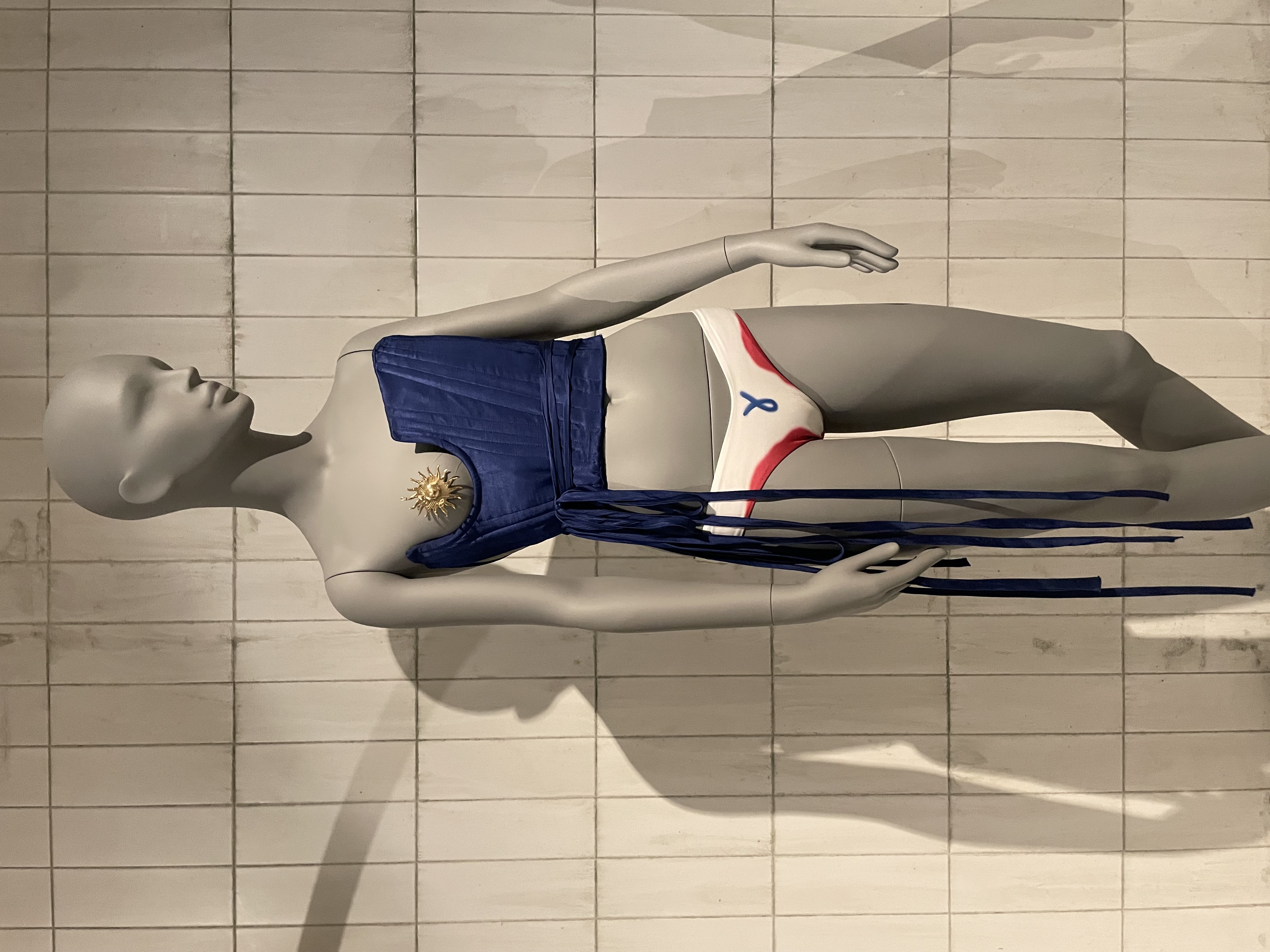

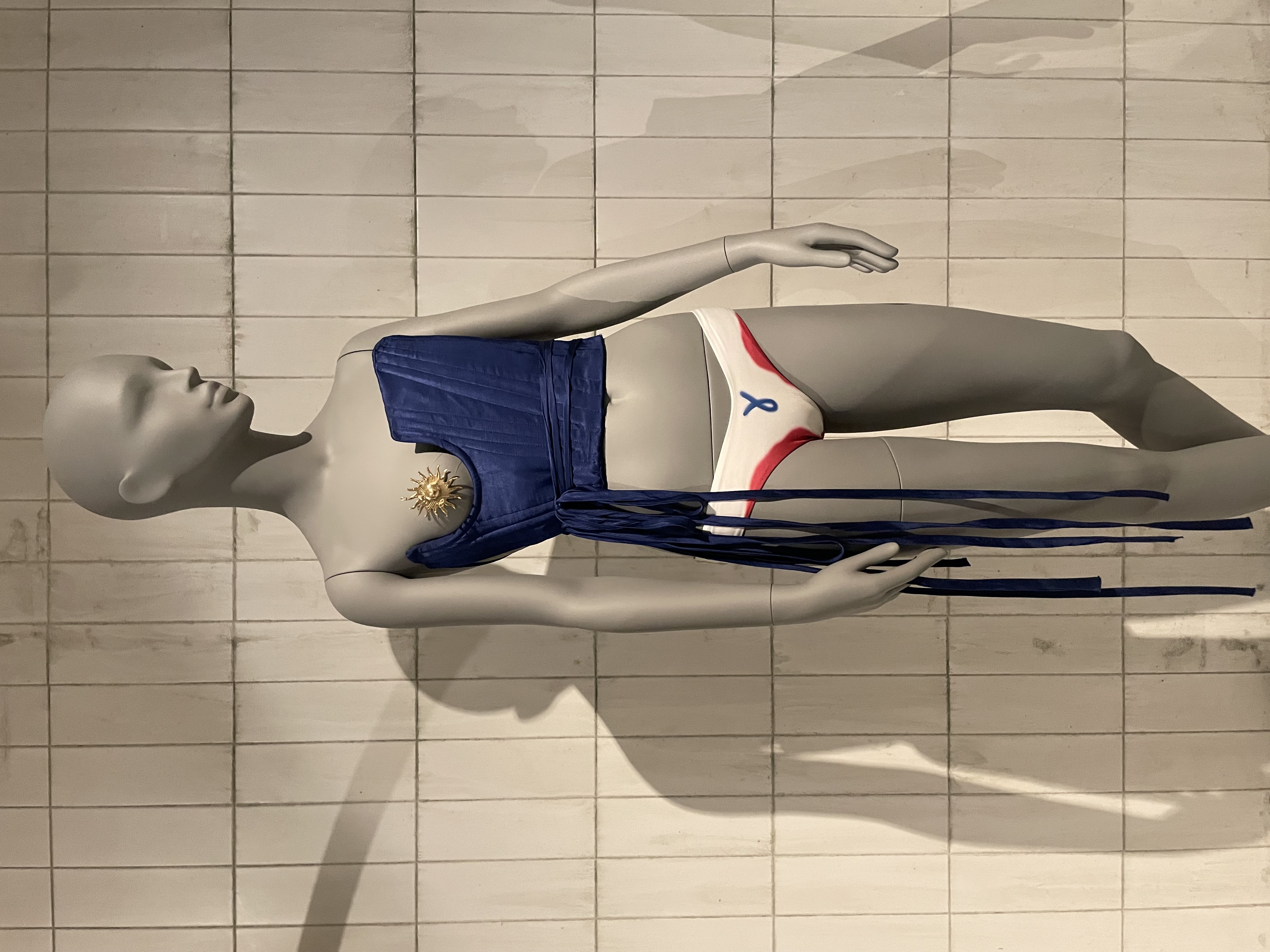

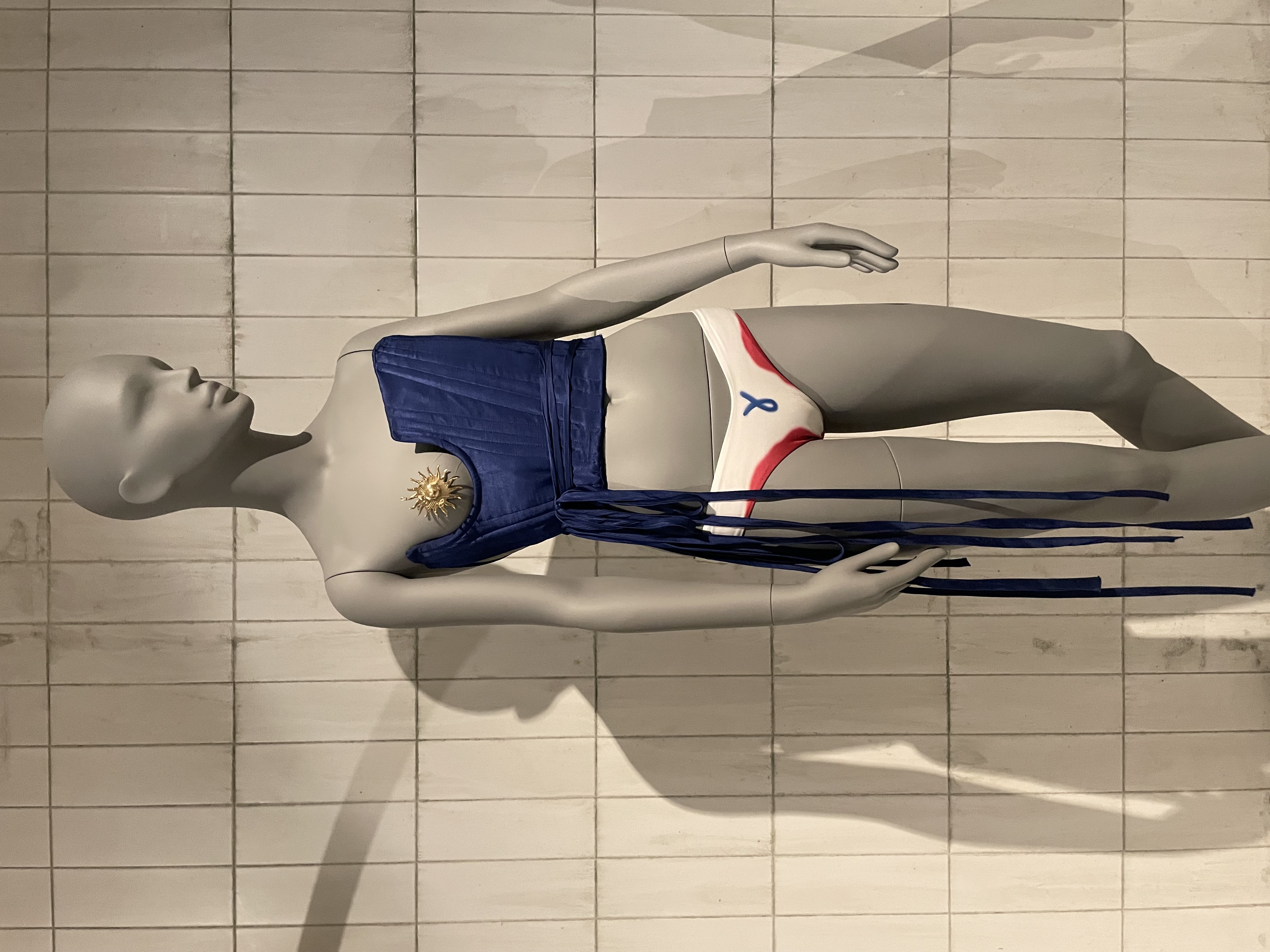

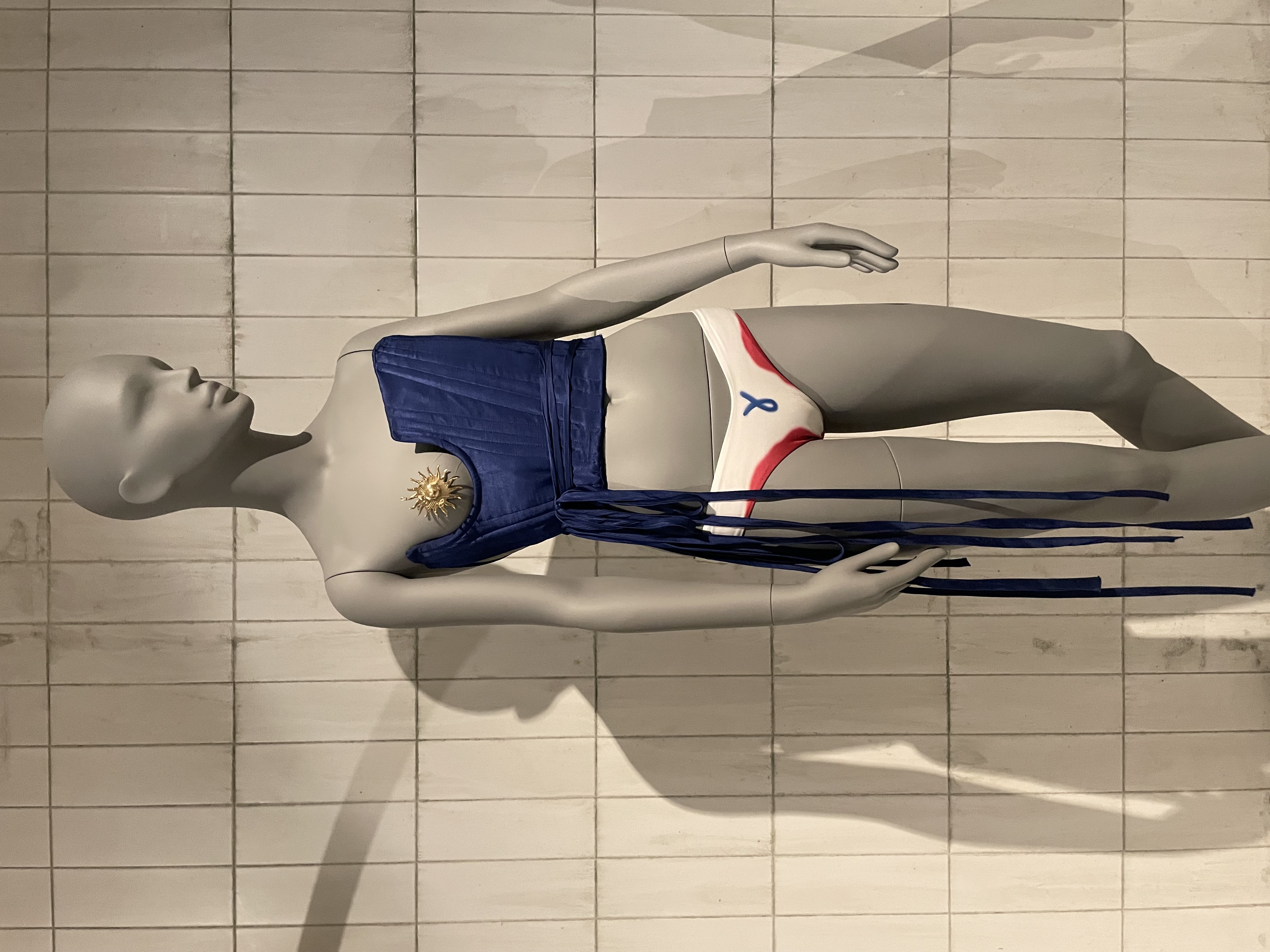

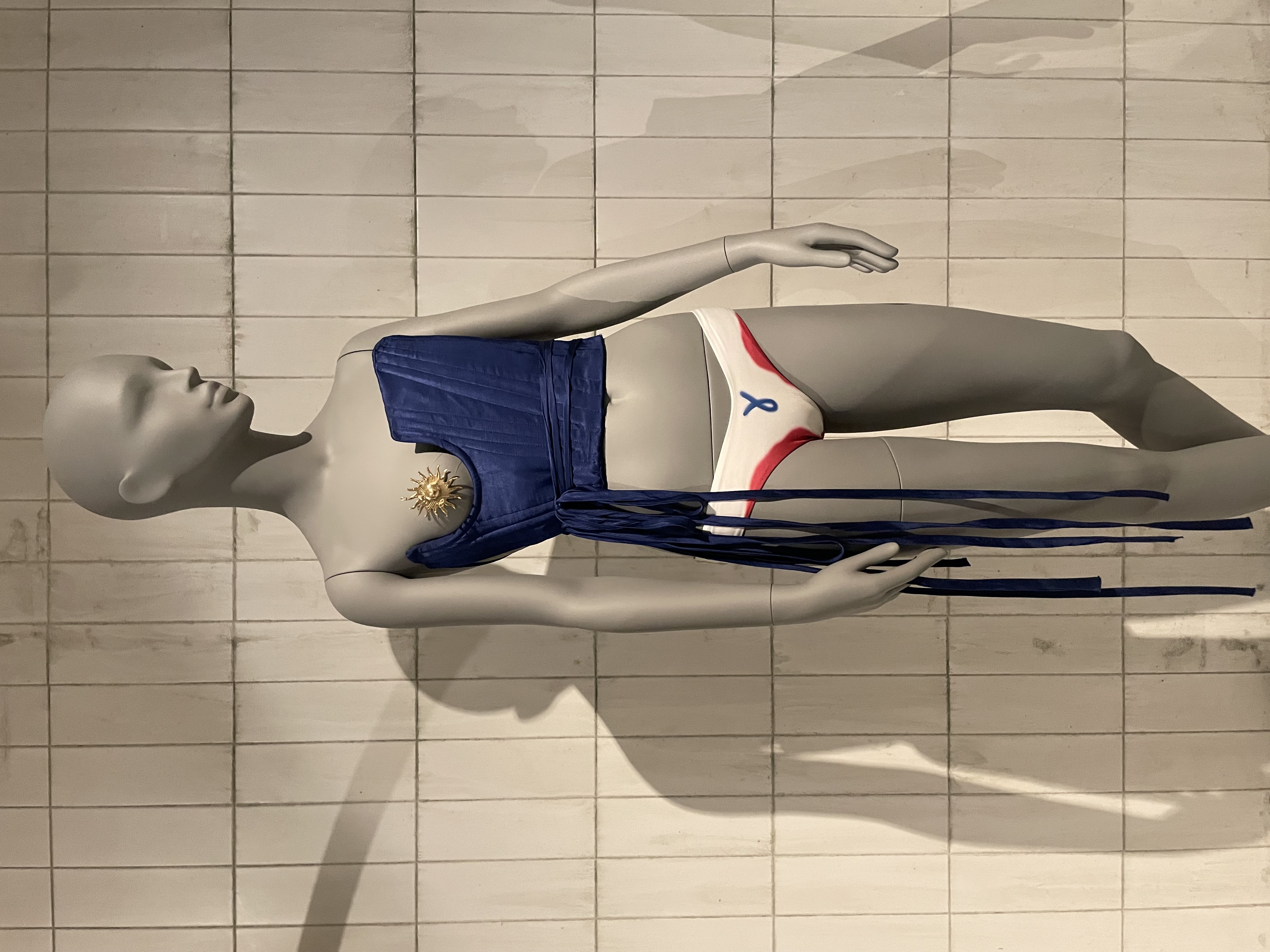

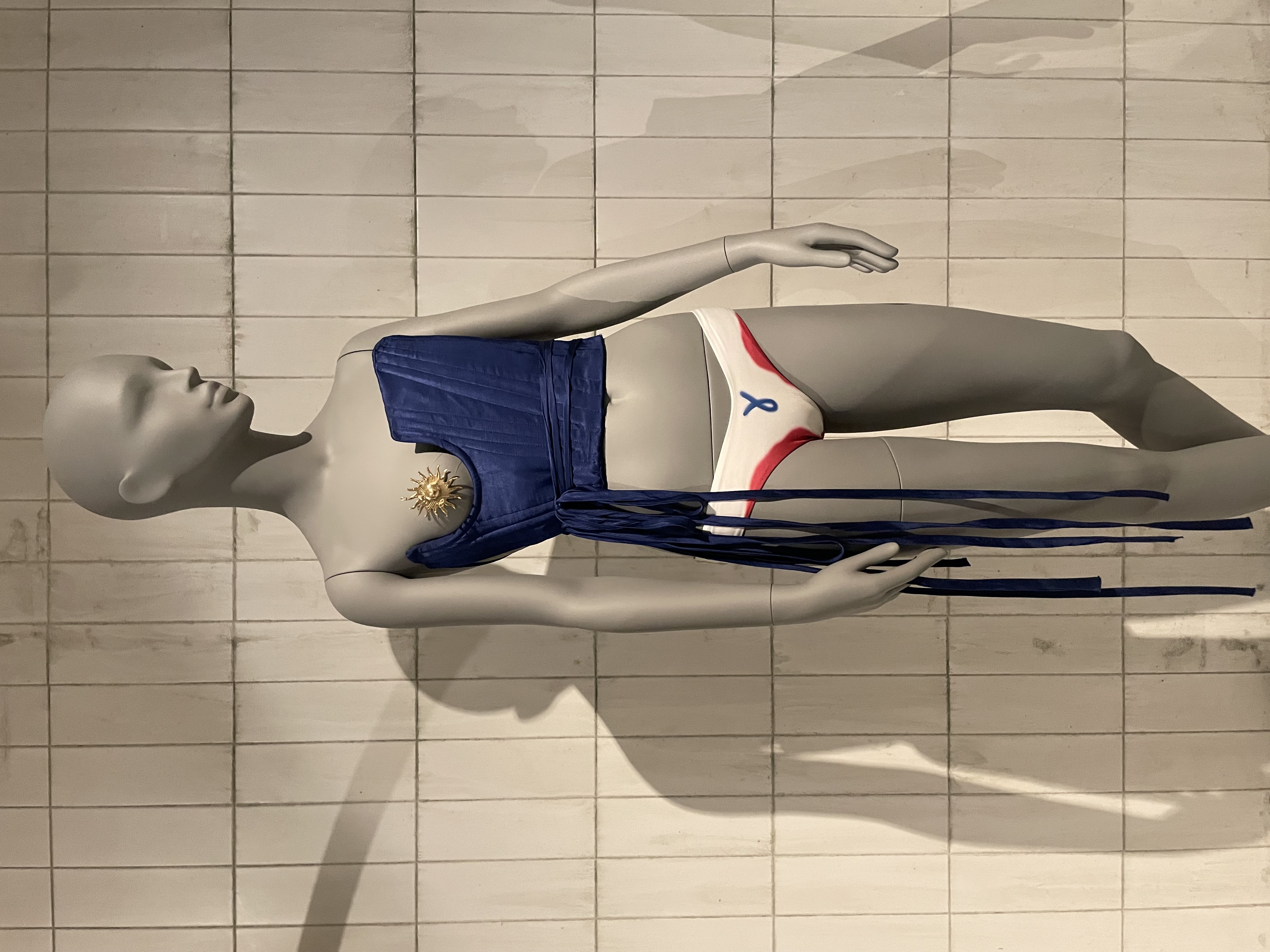

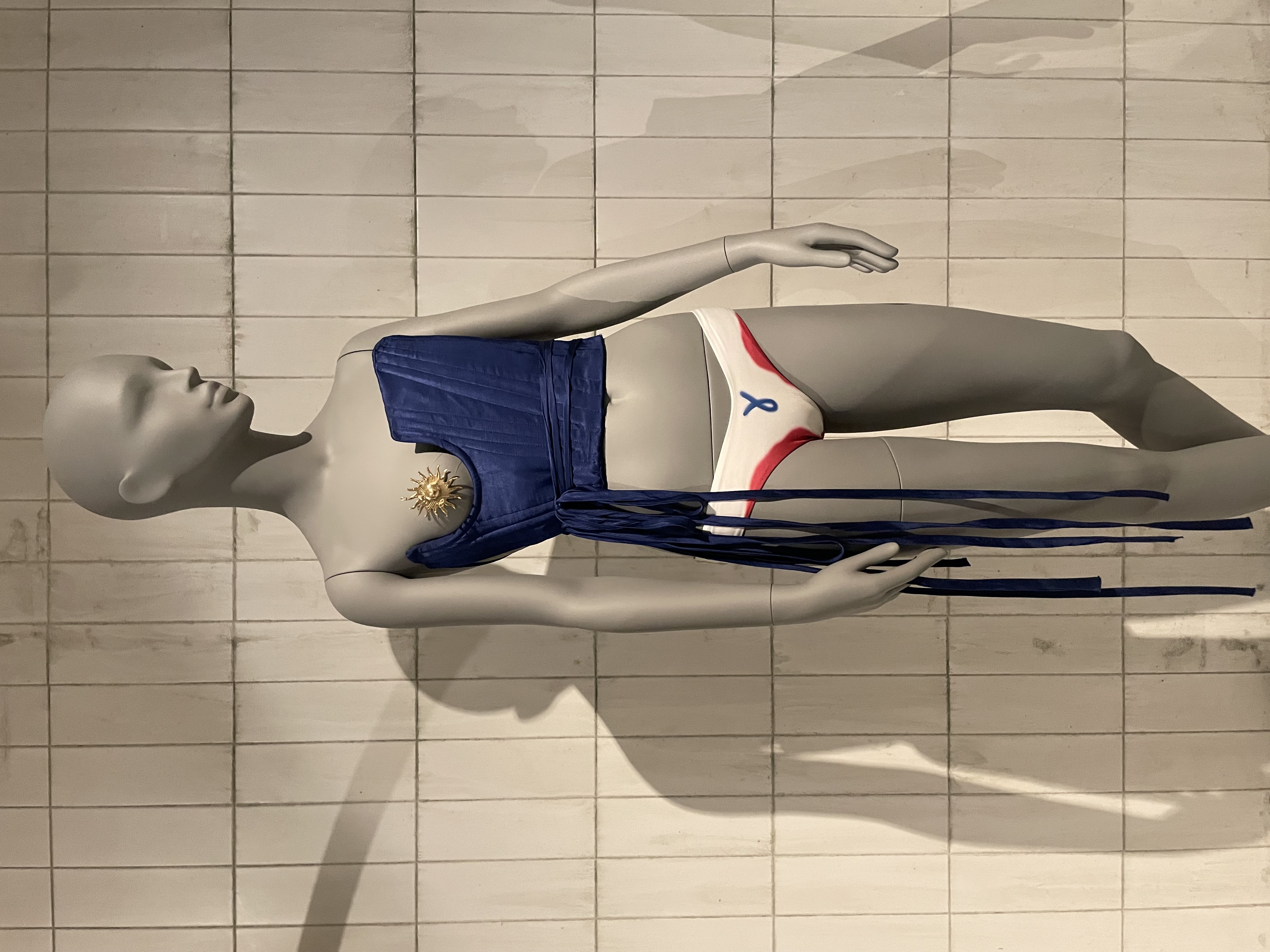

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.

Truthfully, I was first drawn to this exhibition because I can’t resist a clever pun for a title. Dirty Looks successfully delivers on this front, as it plays with the idea of looking dirty and the dirty looks that might attract from others. Beyond the wordplay, I was also keen to get stuck in with some of the ideas this complex subject might address.

When you enter the show, two pairs of wellies set the scene; the late Queen Elizabeth and Kate Moss’s wellies to be precise. These muddy boots are undoubtedly symbols of Britishness – whether it’s old money scruffiness or festival grunge, both attitudes embrace the fact that getting a little dirty is simply part of the deal here.

The exhibition curators then go on to address a range of different themes. The Barbican’s main exhibition space is divided into lots of little boxes, with a vast space in the centre. This layout is quite restrictive and I find it can sometimes feel bitty – a recurring challenge for the curators at the Barbican –, but on the bright side, it allows them to broach subjects from lots of different angles. And it turns out the subject of dirt and fashion is fertile soil.

Keeping to the wordplay, this show takes the ‘dirt’ part of ‘dirty’ as its starting point; that’s dirt as in earth, soil, mud. The clothes on display are rough, ripped, and organic-looking; in harmony with romantic notions of nature and in sharp aesthetic contrast with the sterile, structured constraints of modern society and the built environment.

The curators then look at the use of staining in fashion; how designers embrace the aesthetic of a life well lived – such as drink and food stains, paint marks, rips and so on – and find beauty and intrigue in what might otherwise be considered to be messy and shameful.

They explore the aesthetic of ‘leaky bodies’ as they call them, once again turning what is often designated as a source of shame on its head. Here, the designers use fashion to argue that bodily fluids (blood, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, semen and tears) are only natural, that they are part and parcel of living in a body and therefore should be embraced and celebrated.

And finally, the curators address the dirty side of the fashion industry itself and the environmental damage it causes. Making new clothes is incredibly resource-intensive and has many difficult ethical implications. Fashion is also the third most polluting industry in the world, and massive ‘sacrificial zones’ – where piles and piles of clothes are discarded – are emerging in countries like Ghana, Kenya and Chile. In a couple of different spaces within the exhibition, we see how designers address this issue by using waste material to create new clothes, thus giving a new lease of life to excess material which has previously been discarded and deemed to be impure. Here, as designers make use of excess fabrics and found objects in high fashion, trash is once again turned into treasure.

My only disappointment with this exhibition was the lack of clothing from outside of the high fashion sphere on display. I believe the exhibition would have benefited from showing examples of different textile traditions around the world which incorporate notions of dirt, repair and labour in their remit – such as ‘shoddy’ blankets, Japanese Boro, the quilts of Gee’s Bend and so on. There are nods to these practices amongst the clothing in the show, like when Junya Watanabe’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection referenced Boro and when Acne Studios made a replica of artists’ clothes with their ‘1981 jeans with trompe l’œil paint’, however, it sometimes feels like there’s a dissonance between the intent and the reality. In some ways, creating fake and constructed ‘worn out’ effects rather than real wear and tear is the antithesis of wabi-sabi. Creating artificially aged clothes like ripped jeans can be harmful for the environment, whereas a pair of jeans that has been worn, torn and mended again and again is something worth celebrating.

That being said, Dirty Looks is an enjoyable show for anyone who loves a bit of haute couture and looking at a well-cut garment, particularly if you subscribe to a grunge aesthetic. There are clothes by iconic designers like Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, but the show is also tail-ended with displays spotlighting contemporary designers and brands that are perhaps less known to the general public, rising stars in this (muddy) field, like Ma Ke, Alice Potts, Yuima Nakazato and IAMISIGO (founded by Bubu Ogisi).

Dirty Looks also raises a lot of interesting questions. Whilst it doesn’t show historical examples of textile traditions, it does show the influence of this heritage on contemporary fashion designers. In this sense, high fashion takes on the same function as fine art here, whereby exquisite skills and visual means are used to grapple with contemporary societal issues on the catwalk. It is not life itself (ie, the clothes that people wear in everyday life), but a parallel space once removed from real life, where one can discuss these issues by displaying creative takes on these themes and inviting open conversation.