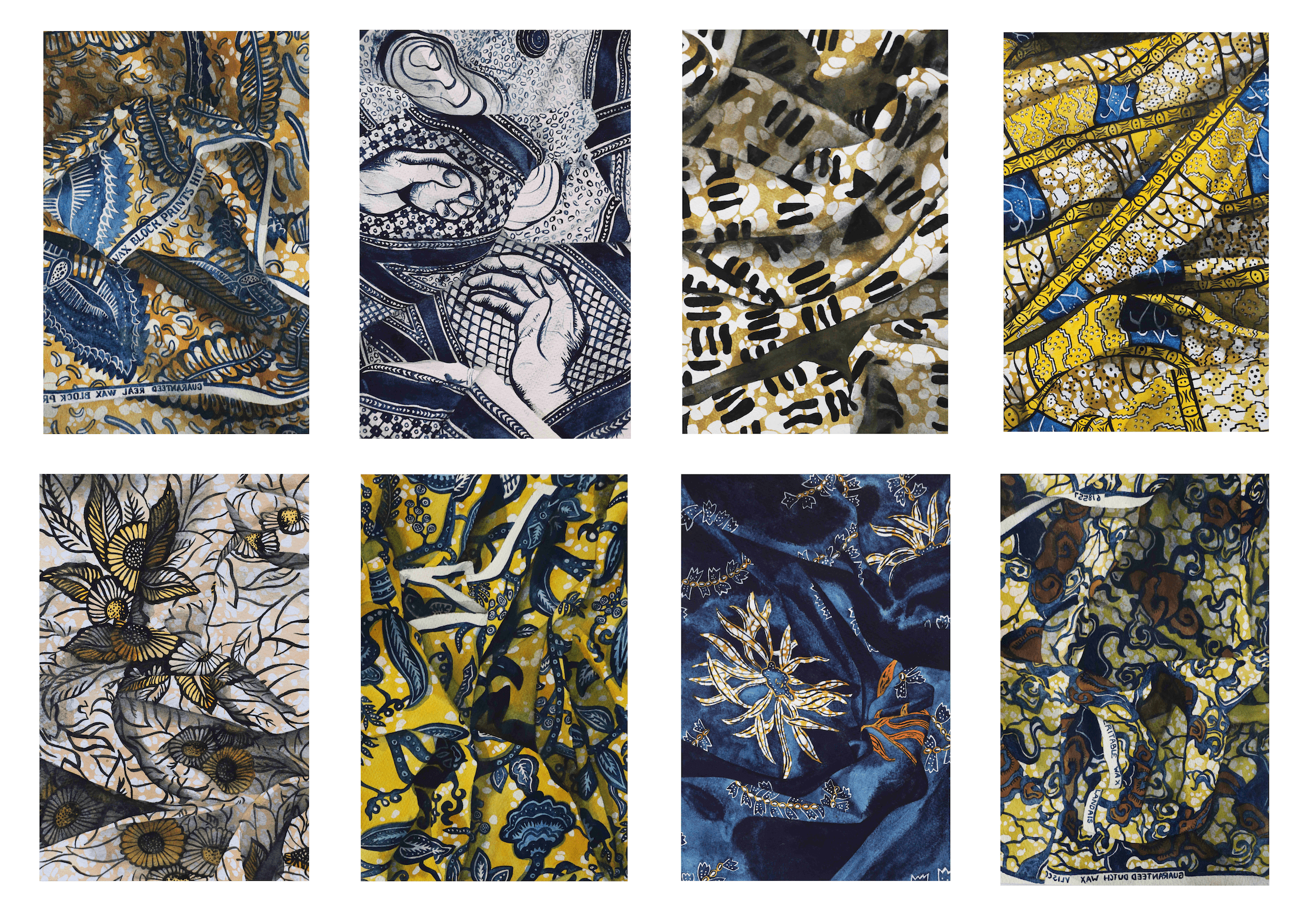

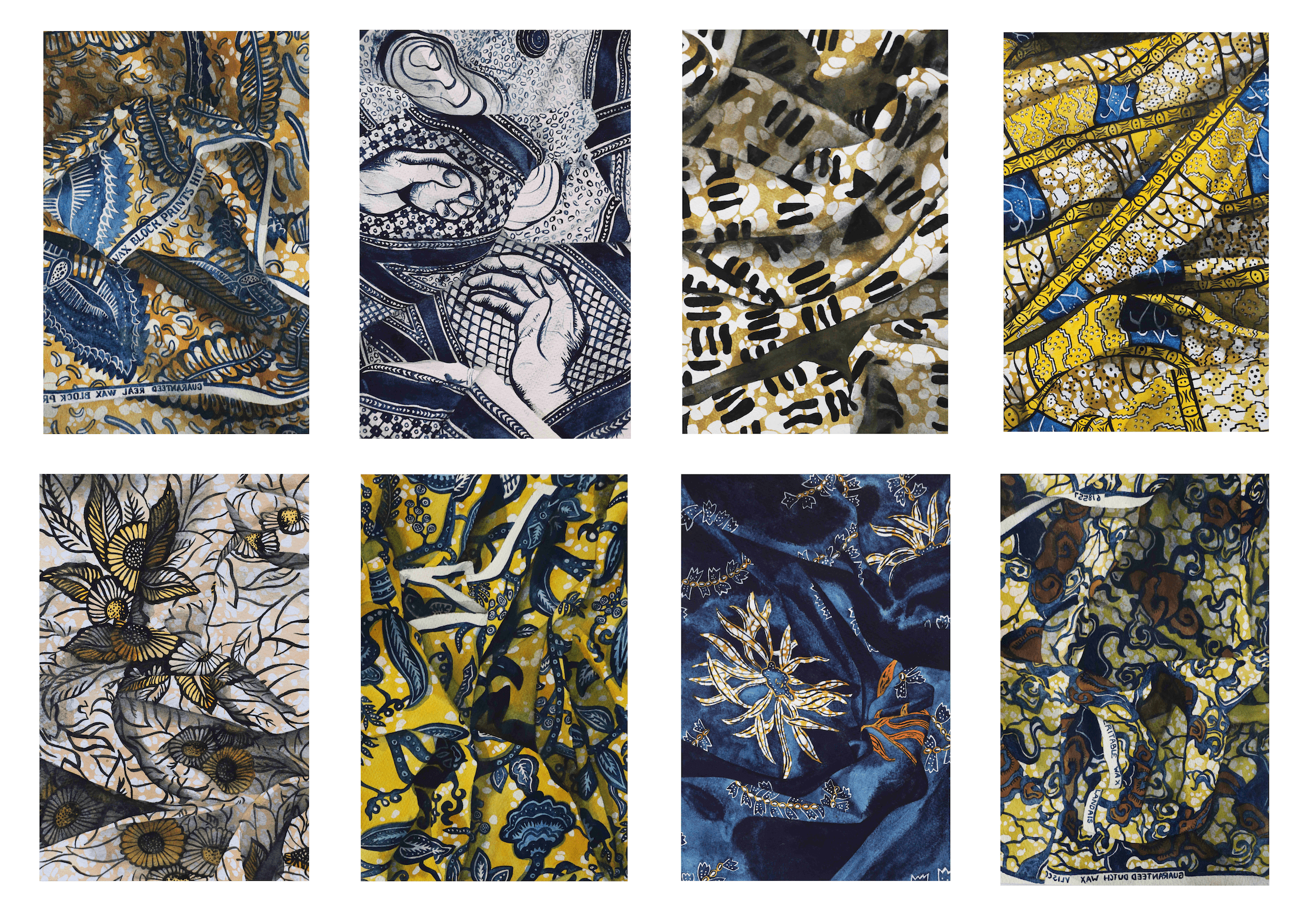

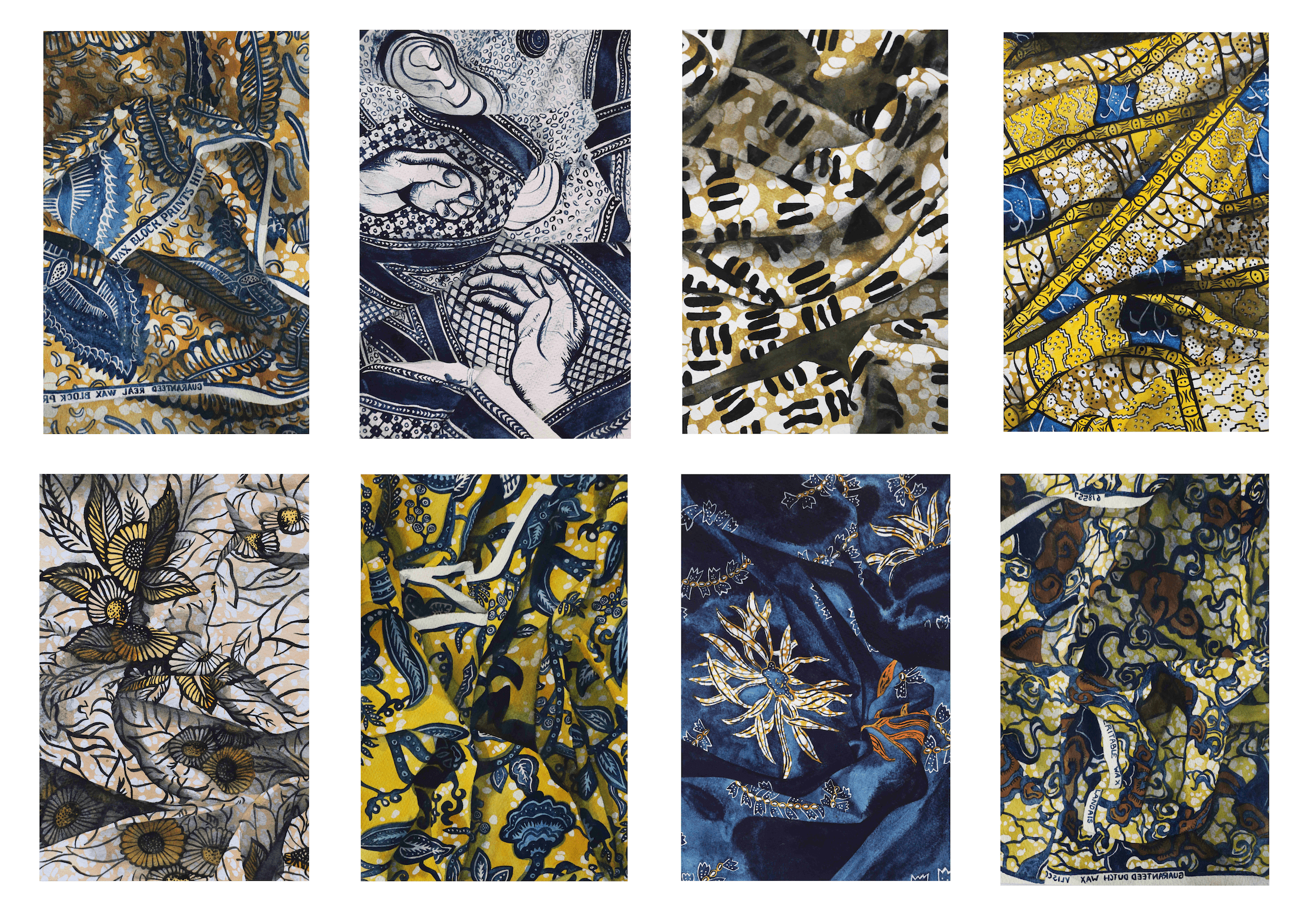

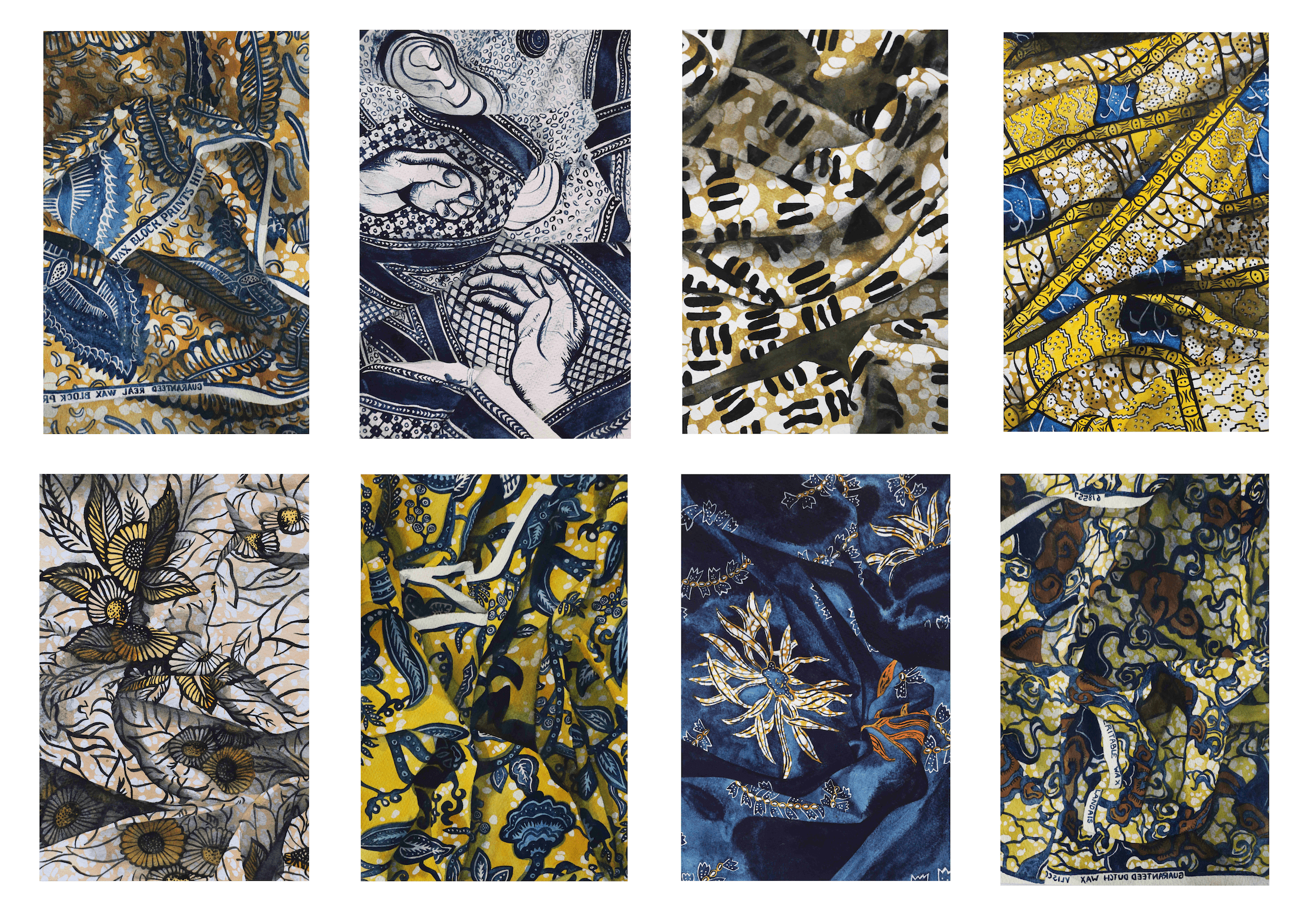

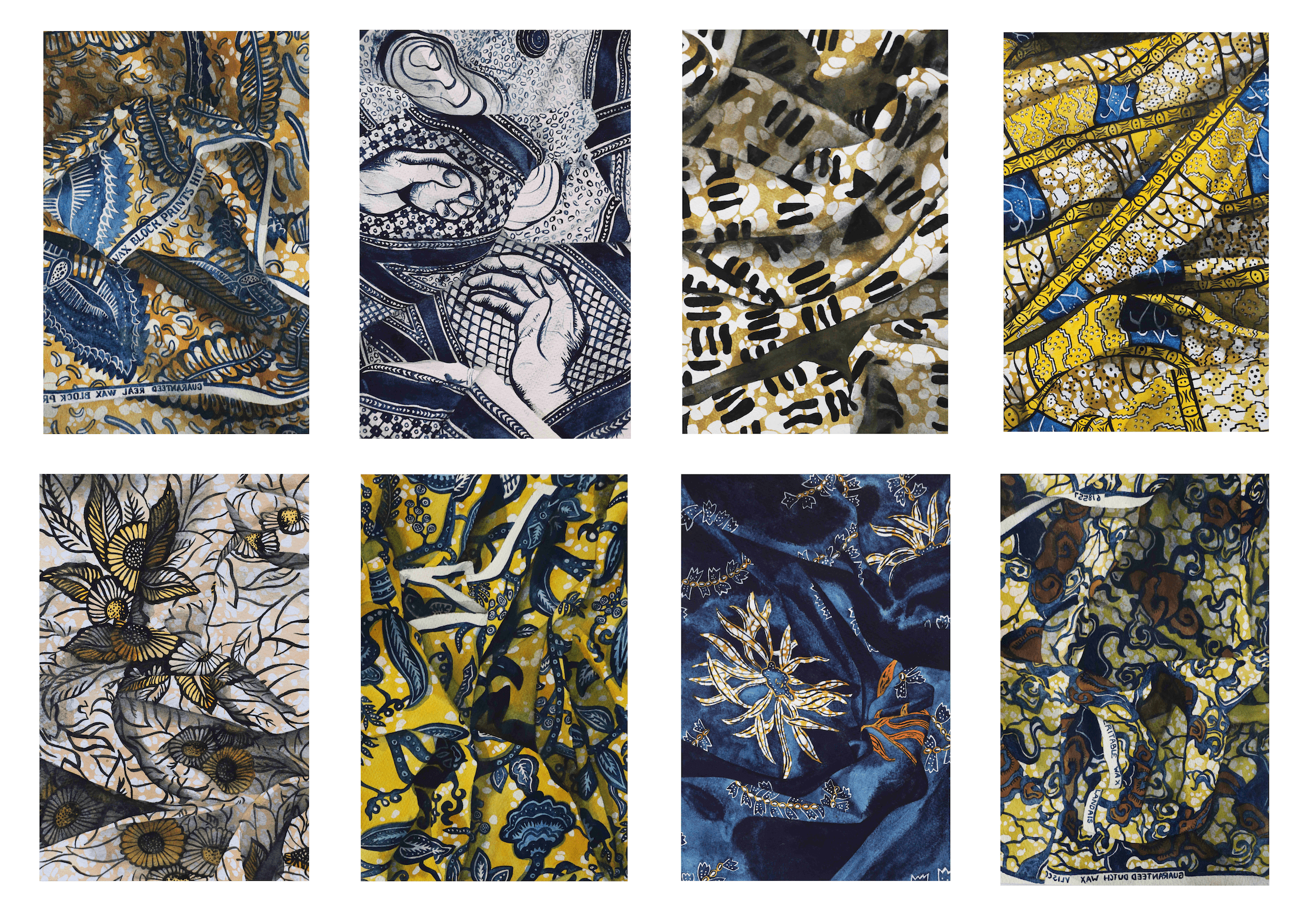

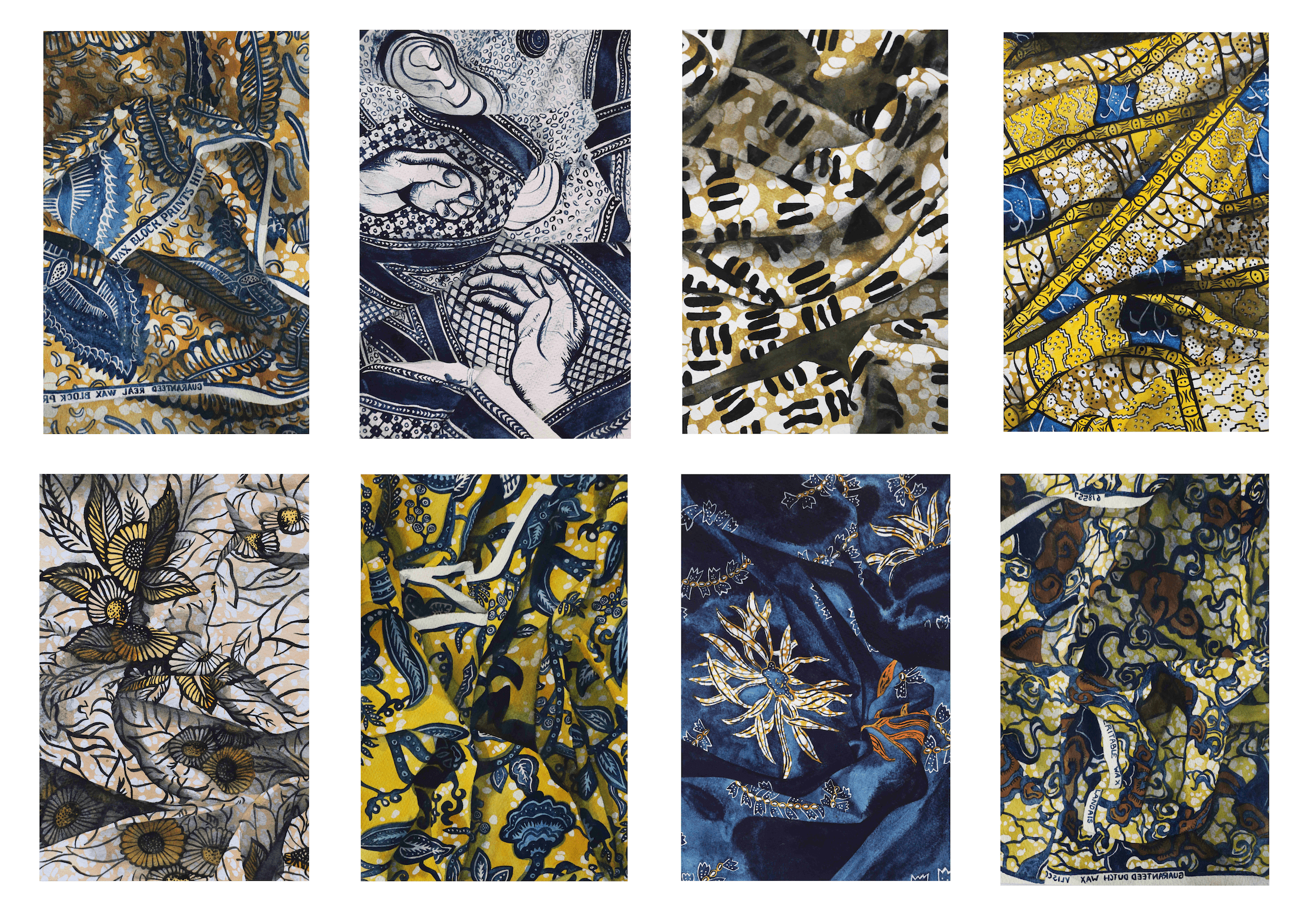

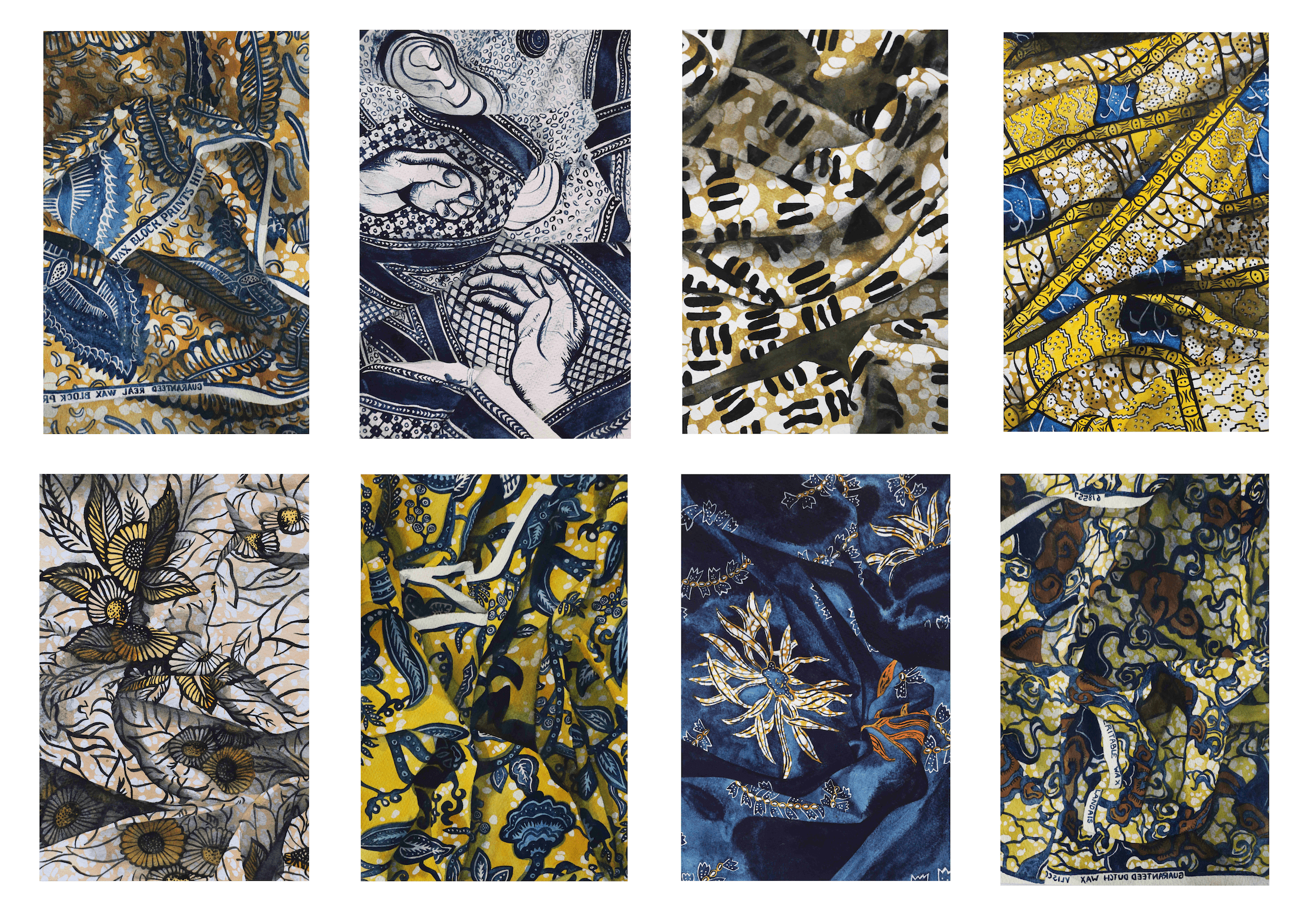

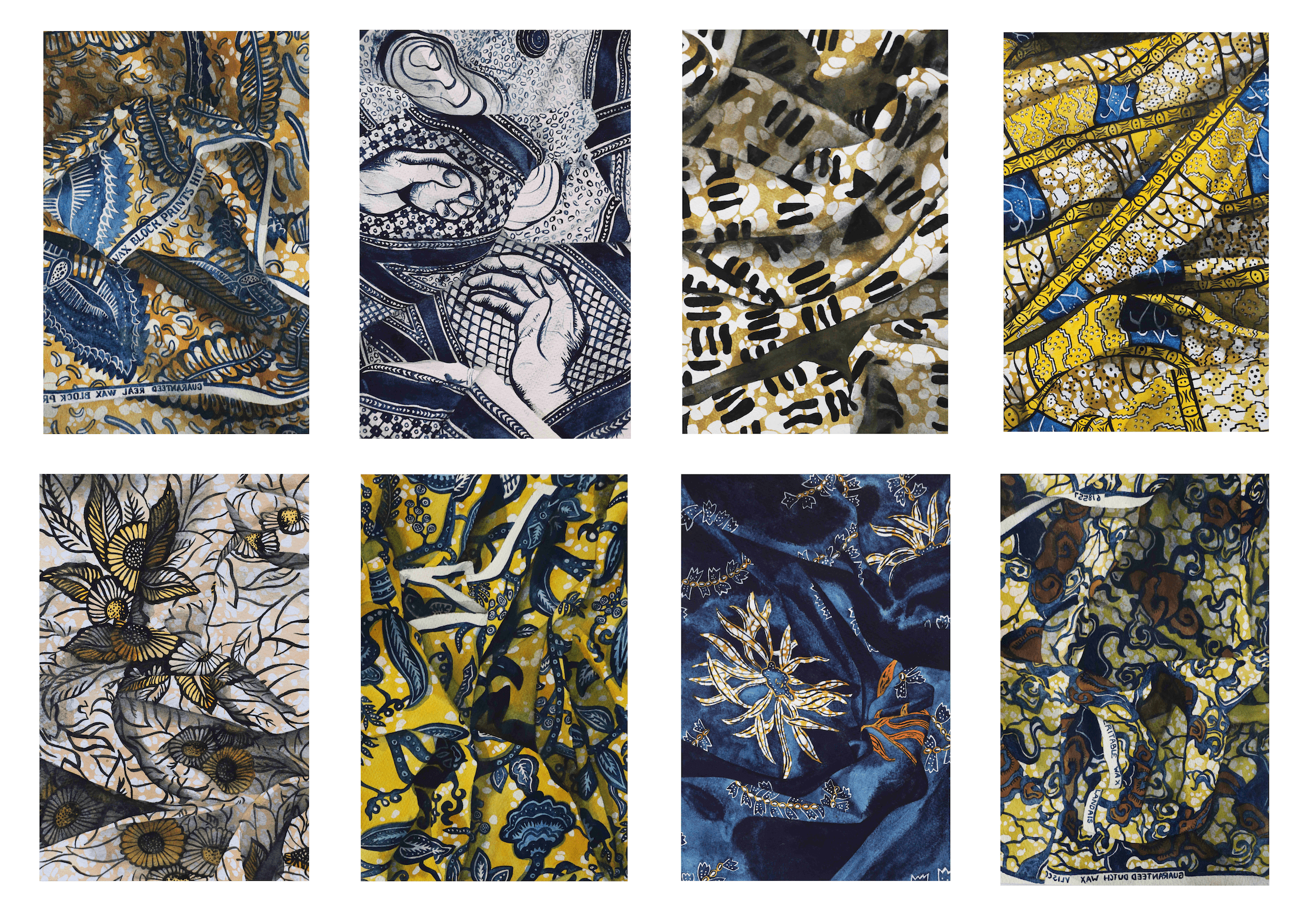

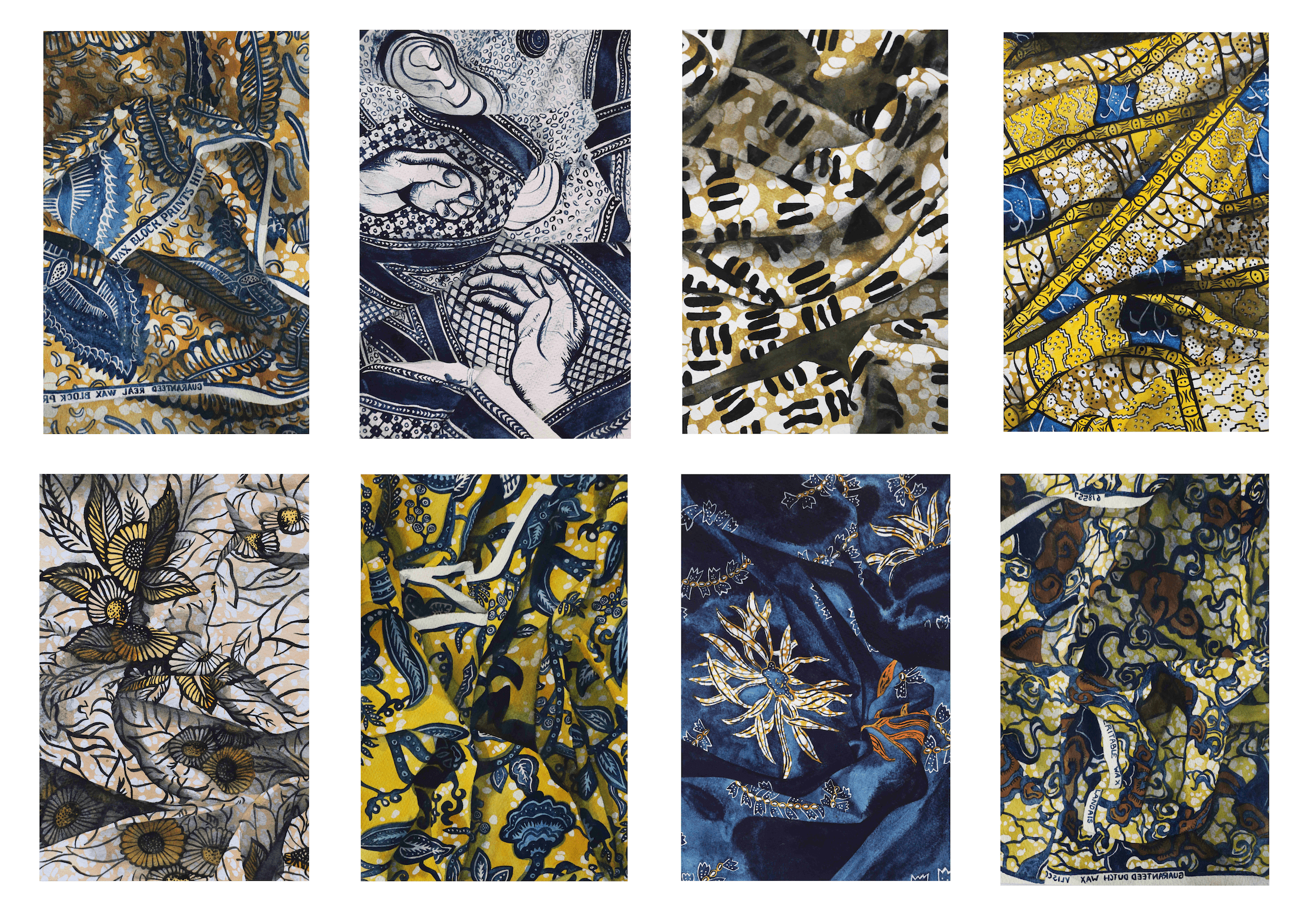

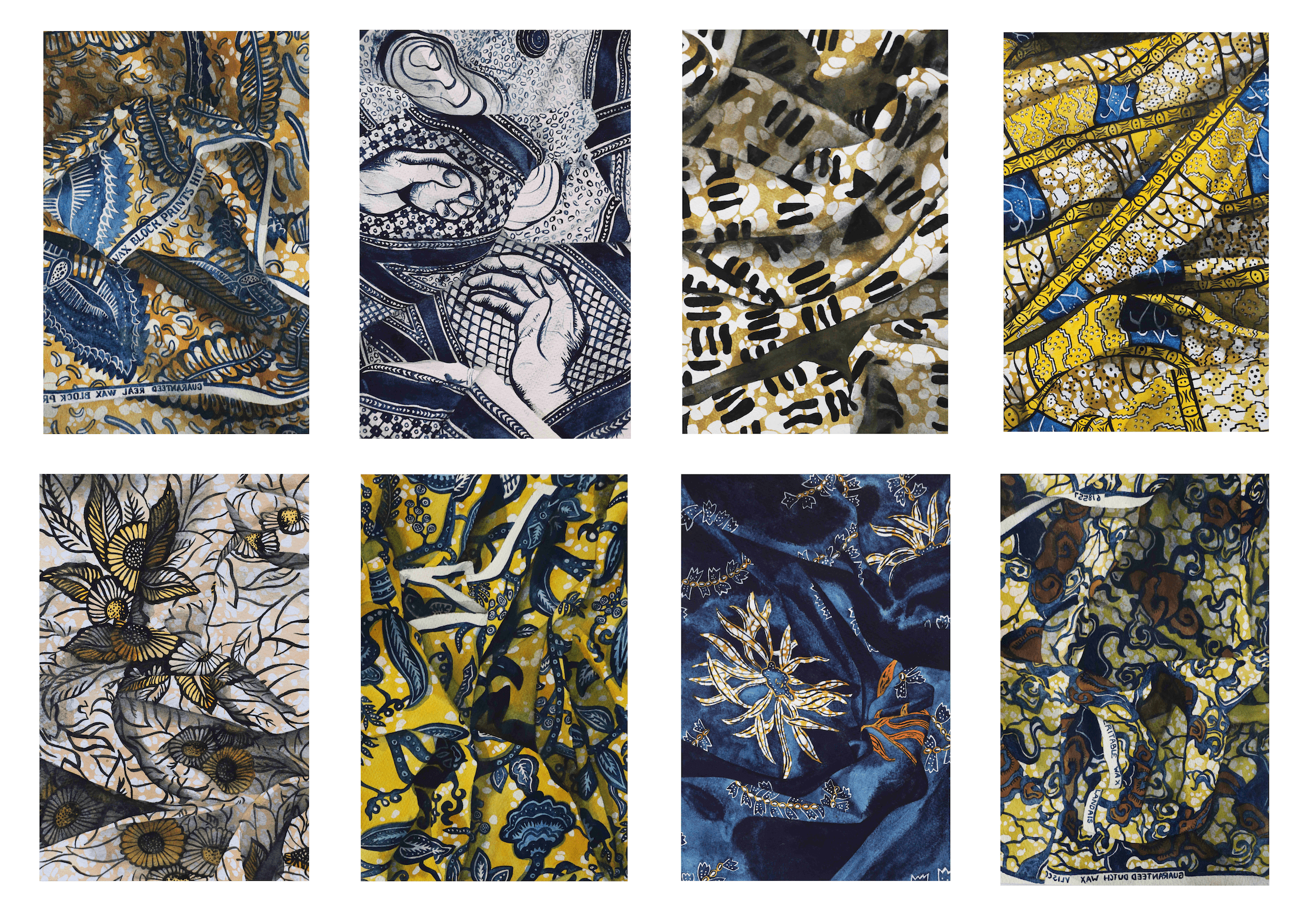

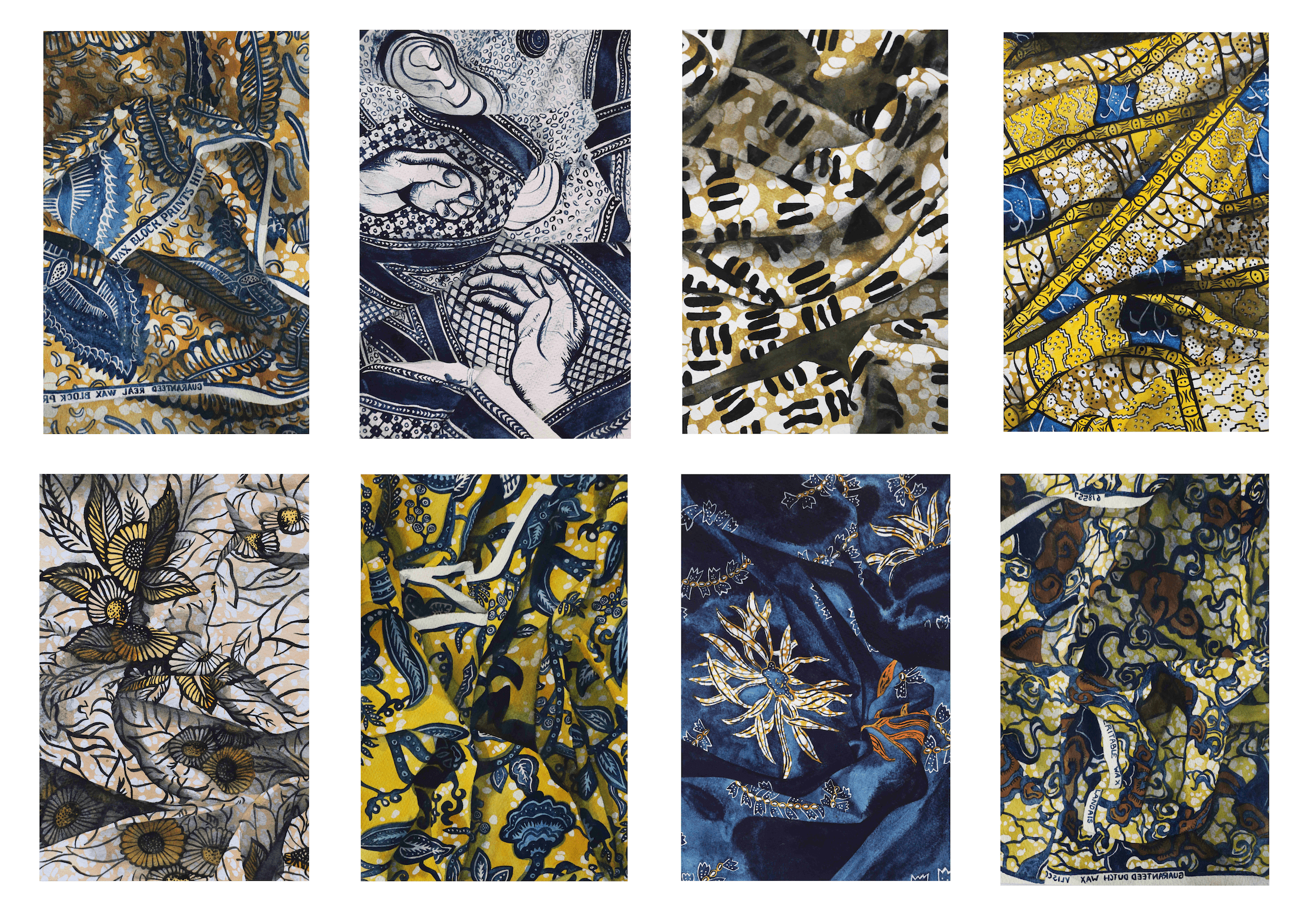

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.

The other people in the room with me were obviously there for various reasons. Some were precisely photographing and measuring garments, while others were drawing a piece of jewellery or creating 3D scans of a wooden sculpture on their iPad. There were parents with their children; kids were encouraged to pursue their interests from a young age and develop a sense of agency, openness, and curiosity early on. Everyone is free to customise their experience as they wish and to nurture their own niche interests and needs. However, I soon discovered that some objects are definitely more popular than others because when I visited, out of six separate groups of people in the room, two were there to see Diana’s iconic white pearl dress and jacket from 1989.

This sense of ease and accessibility that prevailed at the V&A East Storehouse isn’t always the norm in museum contexts. Most museums ‘belong to the public’ because they are funded by the public, but this is the first time I have felt this to be true. Here you can hold items, turn them around, fold them, photograph them, 3D scan them – do whatever as long as you don't damage them or take them home. This felt very different from the usual museum experience, where you can look but can’t touch. Usually, access to the museum collections in storage is obscured and barred from the general public. Here, visitors are truly made to feel like they can get involved.

East London is now home to the V&A Storehouse, a new facility offering a unique 'Order an Object' service. This new, free service is open to all and can serve many functions for creatives and art lovers alike. I used it as a research tool for a project I am currently working on, entitled ‘Origins’ – a series of paintings reflecting on the global stories and histories behind batik textiles – and used this experience as the basis for this account.

In my still life compositions, I tell the stories behind objects. I draw from the decorative to seek out the narratives contained in objects' patterns, forms and materials. So far, I have mostly done this by making drawings, paintings and prints based on my own collection of objects, but this has its limits, of course. It can quickly get costly having to purchase everything you want to depict, and only certain objects are available to purchase in the first place. So, for a few years now, I have been looking to collaborate with various private collectors and public institutions to access their collections and draw from them, which helps to expand my field of visual research greatly. As such, you can imagine my delight about a year ago, when I first heard that the V&A Museum was going to open up every bit of its collections to the public, through a new exhibition space at the V&A Storehouse, as well as a personalised ‘Order an Object’ service, so that you could interact with any of their objects. Since then, I've been eagerly anticipating its opening, and now that I’ve finally made it there, let me tell you, it was well worth the wait.

Firstly, how does this service work? To order an object from the V&A’s collection, you can browse their catalogue online, pick up to five objects to see and add them to your list by clicking the ‘Order an Object’ button. I personally had some technical difficulties, so it took me a few tries before I managed to book an appointment, but it’s actually very simple. Just remember to add all the objects to your list successively in a single tab on your browser, rather than making my mistake and adding them across multiple tabs. It’s also worth noting that some objects might be accessed from V&A’s South Kensington location, not necessarily at V&A East. Luckily for me, though, the textiles I wanted to see were located at the Storehouse, so I got to sneak a peek at the newly revamped museum facilities while I was at it.

From a distance, the building of V&A East Storehouse just looks like a big box – the first reminder that, as a storehouse, this place’s primary purpose is function over form. As you enter through the front doors, there’s a fairly basic reception area where everyone is asked to drop off their bags in lockers. With some time to spare before my scheduled appointment to experience the ‘Order an Object’ service, I thought I’d check out the main exhibition space. I went up a set of stairs, stepped in through a corridor lined with sculptural busts in crates, before being released into a vast, expansive space spanning multiple floors. This space is almost church-like; it’s awe-inspiring and eclectic. From there on, there isn’t a single prescribed path to take, but rather an array of options and a cornucopia of objects to look at. The treasure-hunt feeling that ensued seemed to create a lot of buzz and curiosity from the visitors. I enjoyed the slightly surreal sight of all the objects and sculptures in their crates, cradled by wooden bars and straps for safe storage and transport, but each to their own… And that’s precisely the point; there is a lot to look at, and it is up to you, the viewer, to decide what you think is worth looking at.

The aesthetic straddles the line between storage space and exhibition space. It is curated and organic at once, and it is ever-changing. Here, the museum turns an eye towards itself, and we’re constantly reminded that this is a working museum. Making what is usually invisible visible is the central function of this space. Visitors can see objects that usually stay in the dark, we can watch as museum-workers go about their daily business – the analysis, conservation and presentation of art and objects – and visibility is even part of the aesthetic of the building, as you can always see through the glass walls and metal grid floors across to different sections.

But I digress; I’m not here to fangirl about the collections on display, but to talk about my experience of the V&A’s order an object service, which is on offer here. So what’s that like? At the reception for this section of the museum – a study centre called the Clothworkers' Centre for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion – I was asked to check in and wash my hands before entering. Quite rightly, I was presented with a set of rules, which included wearing gloves to handle certain objects and asking for help when moving fragile pieces, for example. But this introduction also felt welcoming; I could ask the staff for further information about the objects if needed – and whilst I got the sense that they pull this information from the V&A’s website (which tends to be pretty generous already), it’s worth asking anyway because at best, you might find yourself in the company of an expert in the field you’re studying, and at worst, you’ve started a conversation about the objects that you’re intrigued by.

The room is made up of about five large tables with a few people at each table, dark wooden storage cupboards to the sides, bookshelves at one end and a staff desk at the other. The aesthetic is somewhere between a scientific lab and the British Museum’s ‘Enlightenment’ room, with its wooden cabinets of curiosities. Above, there’s a balcony with museum visitors watching the scene as it unfolds. The atmosphere in the room is a bit like that of a library; quiet and peaceful as everyone studies their objects. I found the staff kind, patient and helpful. While I was careful not to damage these precious objects in any way, I quickly felt at ease in the space. But there is also a sense of awe in the air, like everyone feels lucky to be there in the presence of these admired objects.

I ordered a series of batik textiles from the V&A to complement my ‘Origins’ series. Batik textiles, also known as Ankara or Dutch Wax, have a complex global history. Originally from Indonesia, these wax-resist fabrics were imitated by European colonisers who were trying to replicate them and sell them back to the Indonesian population. Still, when they failed to make a profit, European producers redirected their products towards the West African market instead, and now these textiles are closely associated with African culture. I am intrigued by this multifaceted history and the cultural dynamics it reveals. My goal is to make a large series of paintings of real batik textiles that were made at different times in different places and to place them side by side so that viewers can compare and contrast their patterns and relate this to the stories behind the textiles. As such, at the V&A, I asked to see five imitation-batik textiles that were made in Manchester in the first half of the 20th century so that I could manipulate them into shape and take photos of them, from which I would create paintings back in the studio. Happily, I was able to do just that: getting up close and personal, picking them up, moving them around, and because these particular fabrics weren’t too fragile, I wasn’t obliged to wear gloves, so I could also feel the texture of the fabric, how pliable it was and so on.