From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

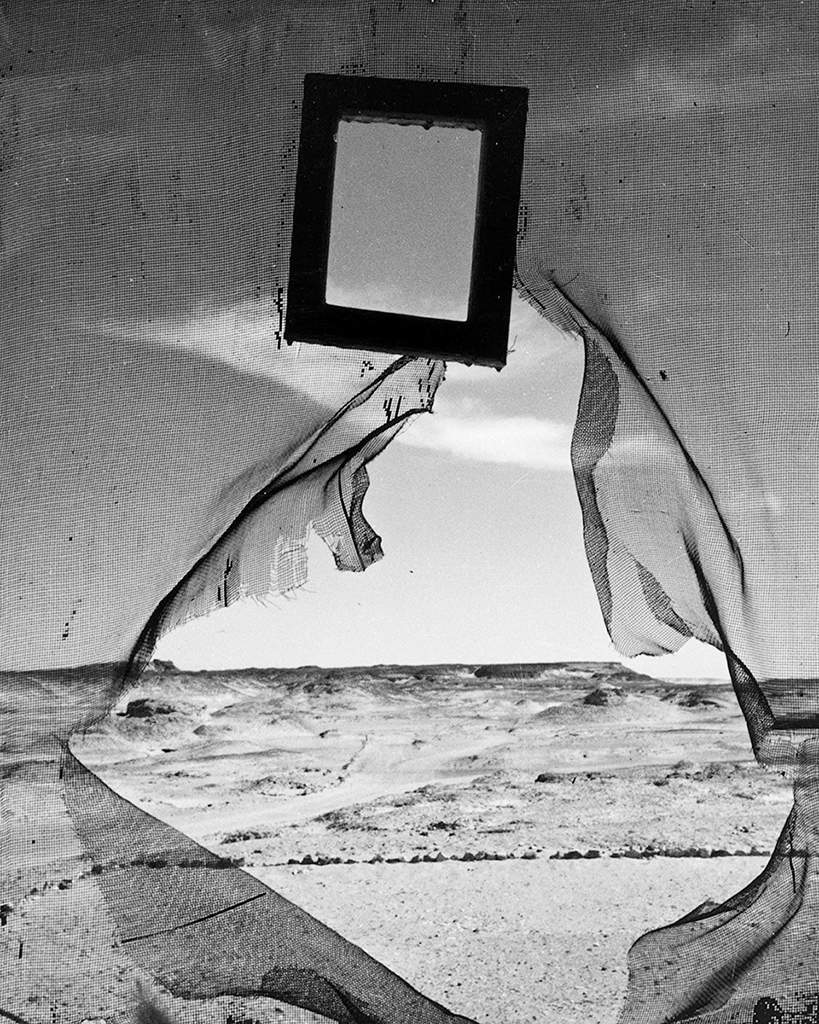

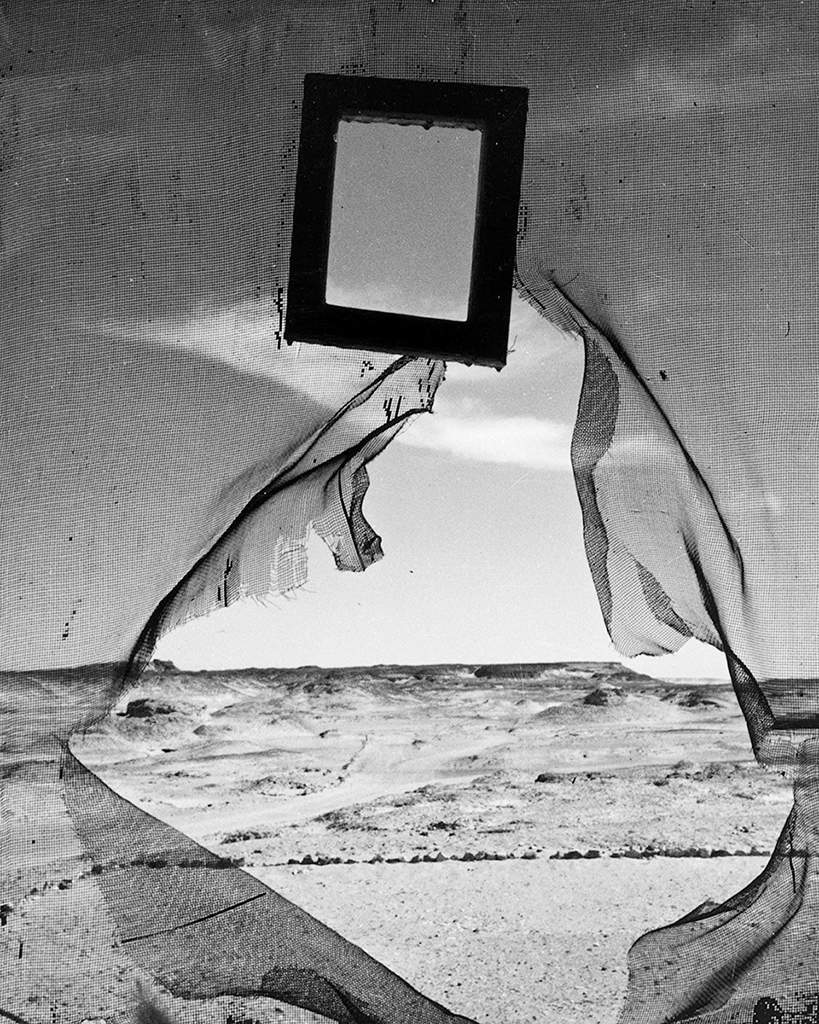

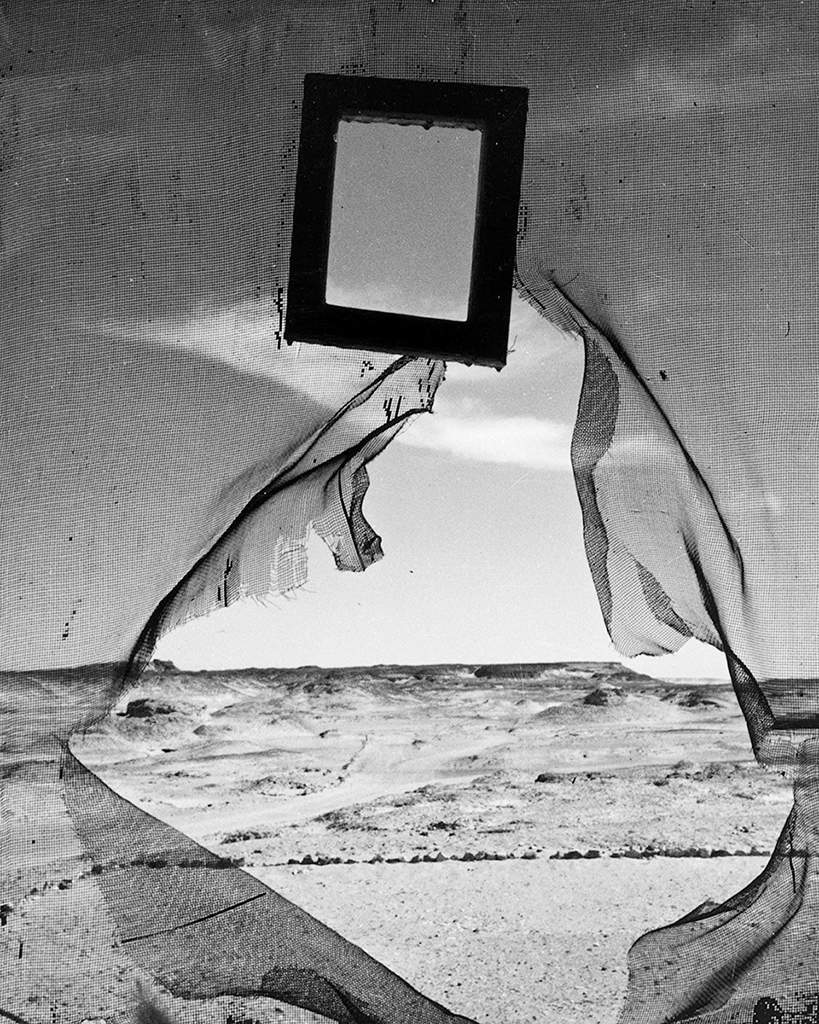

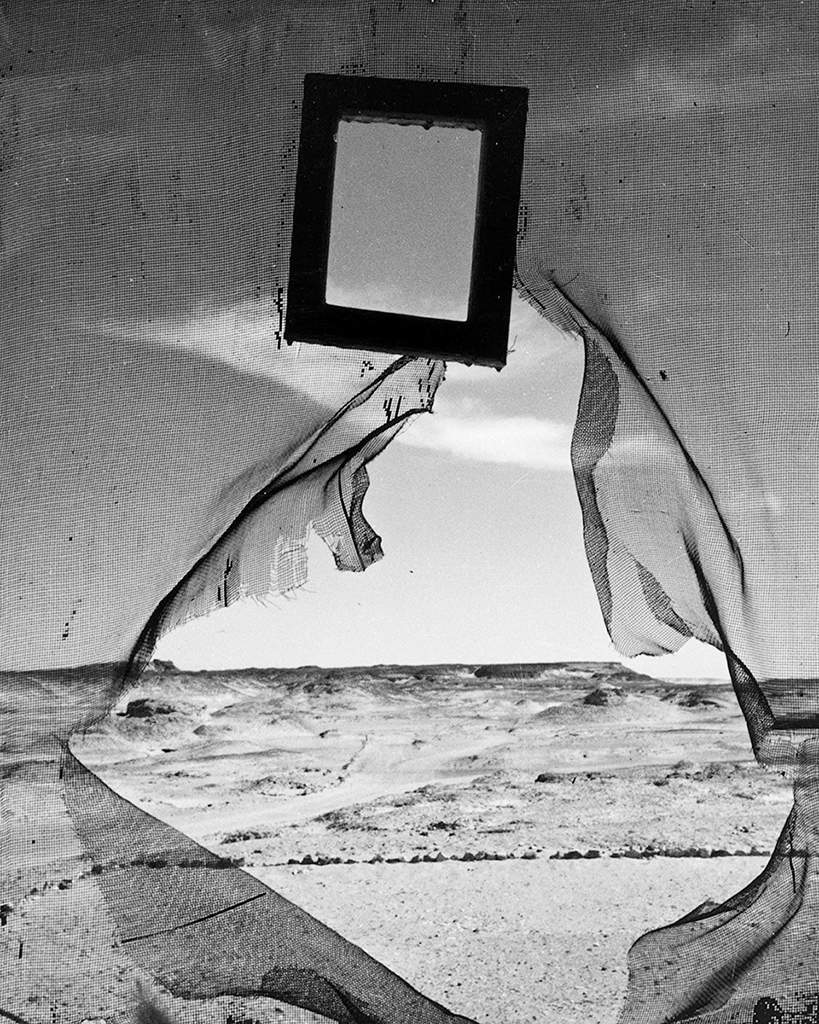

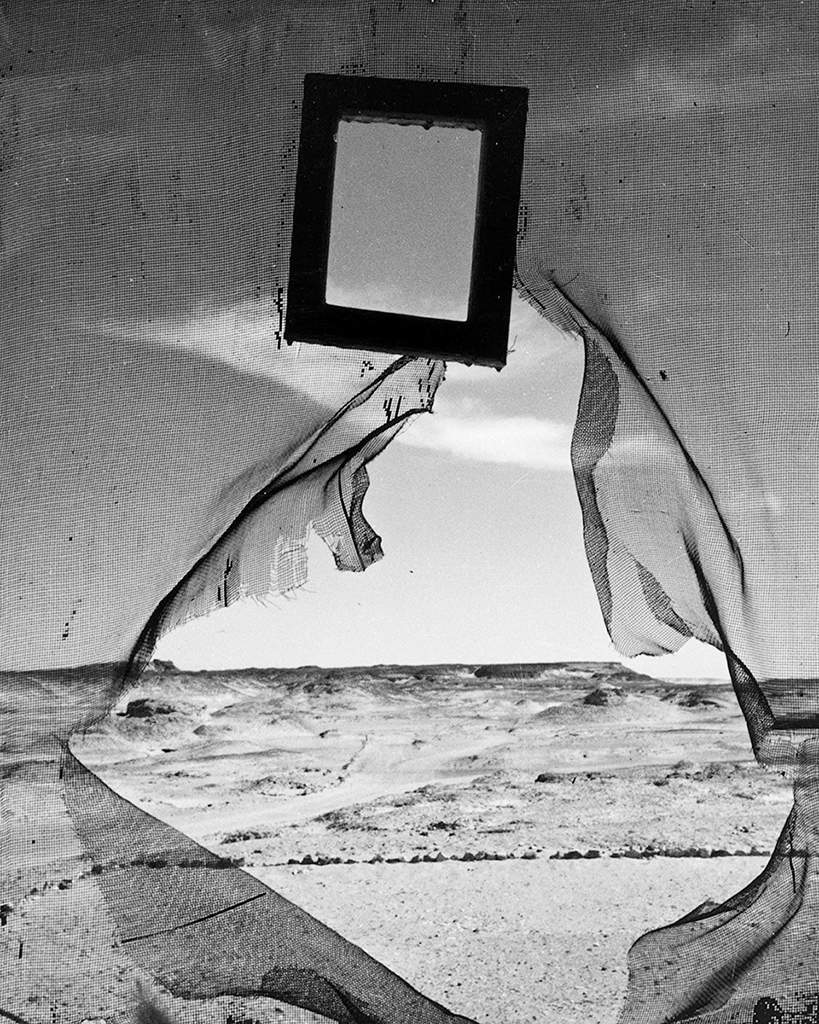

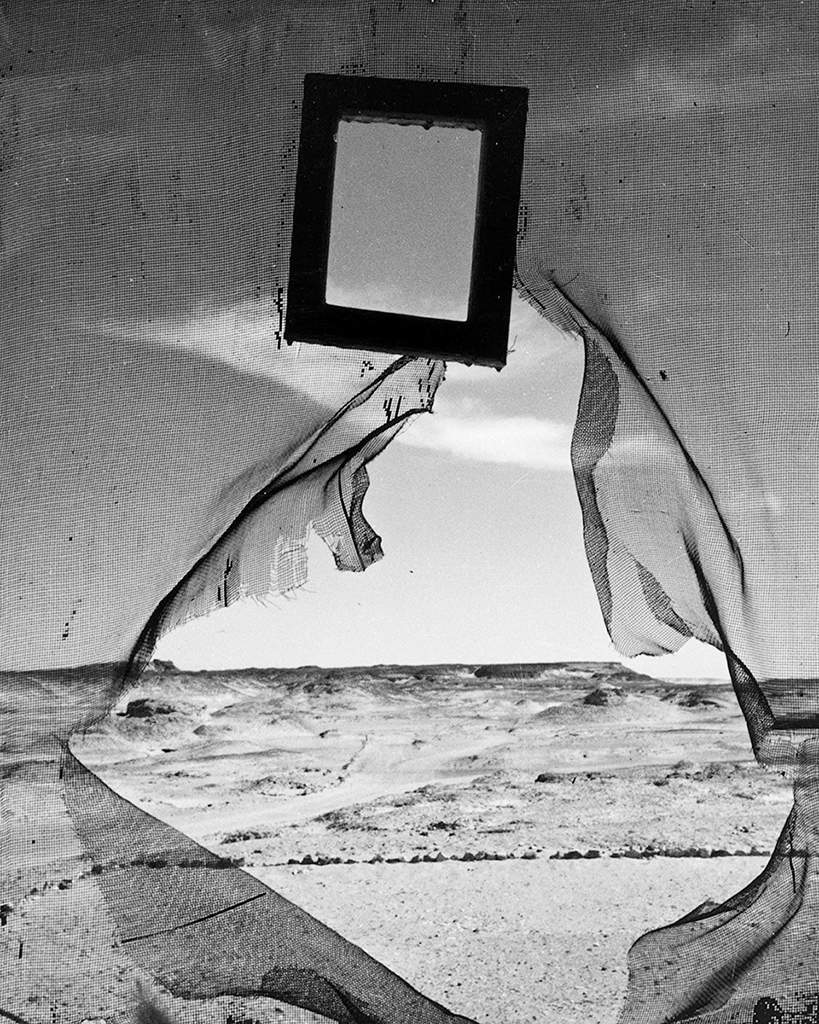

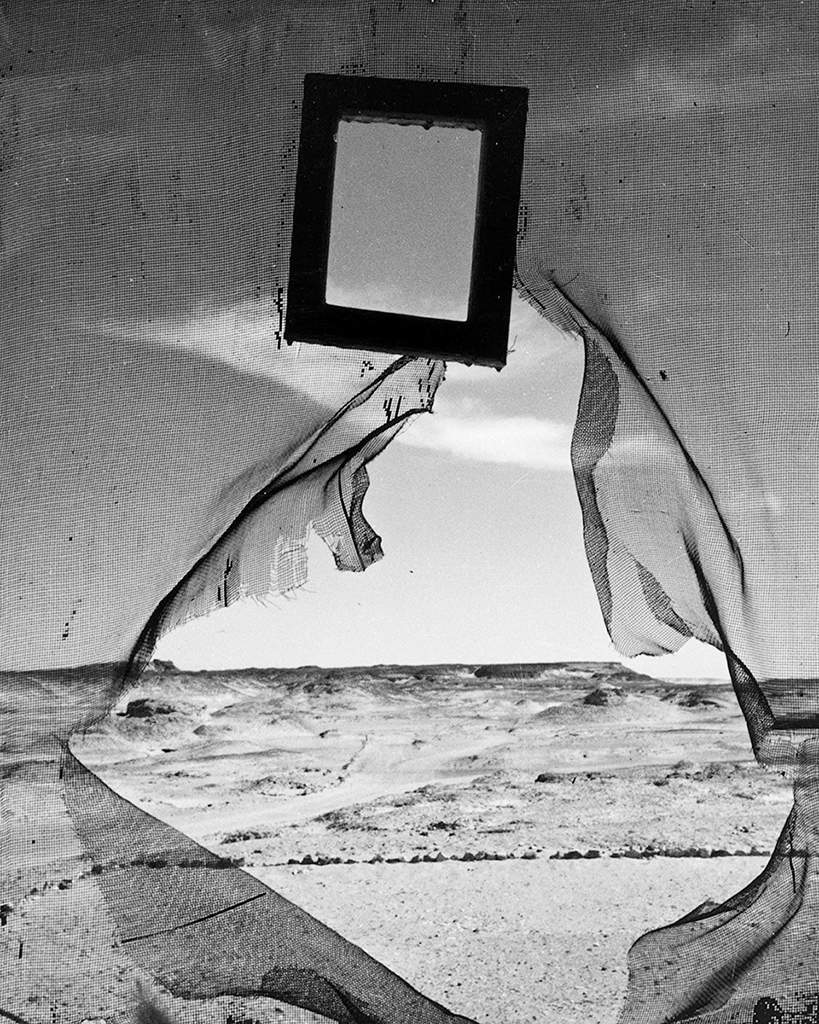

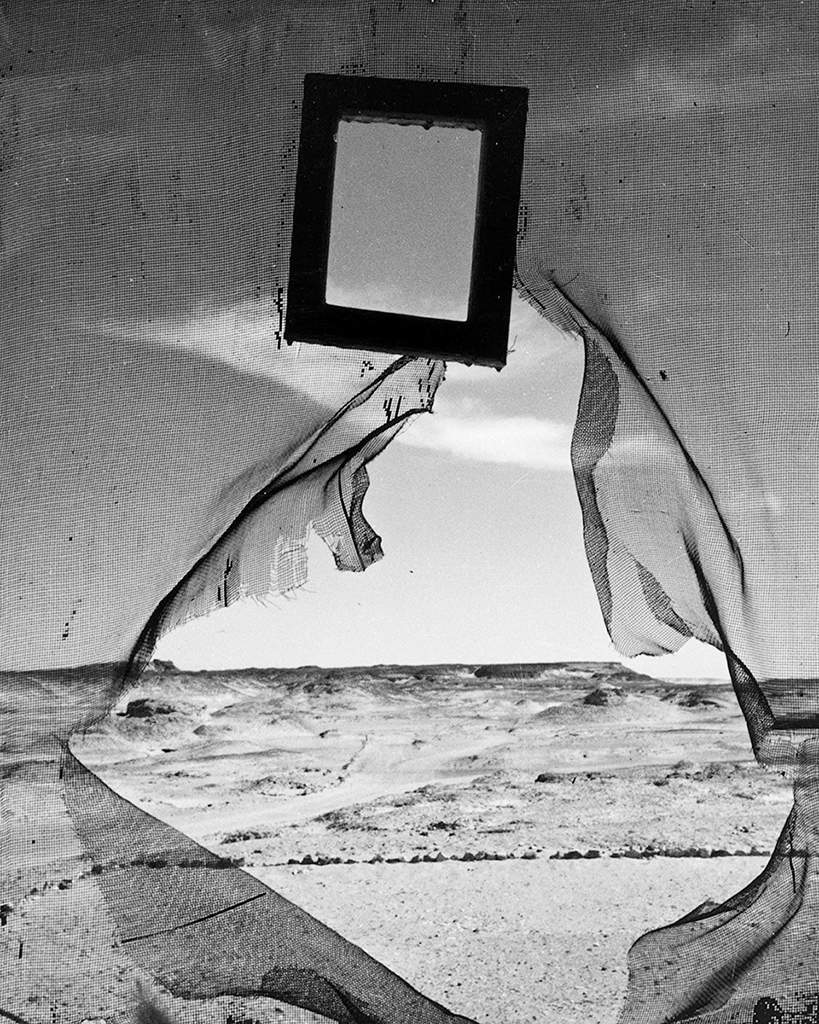

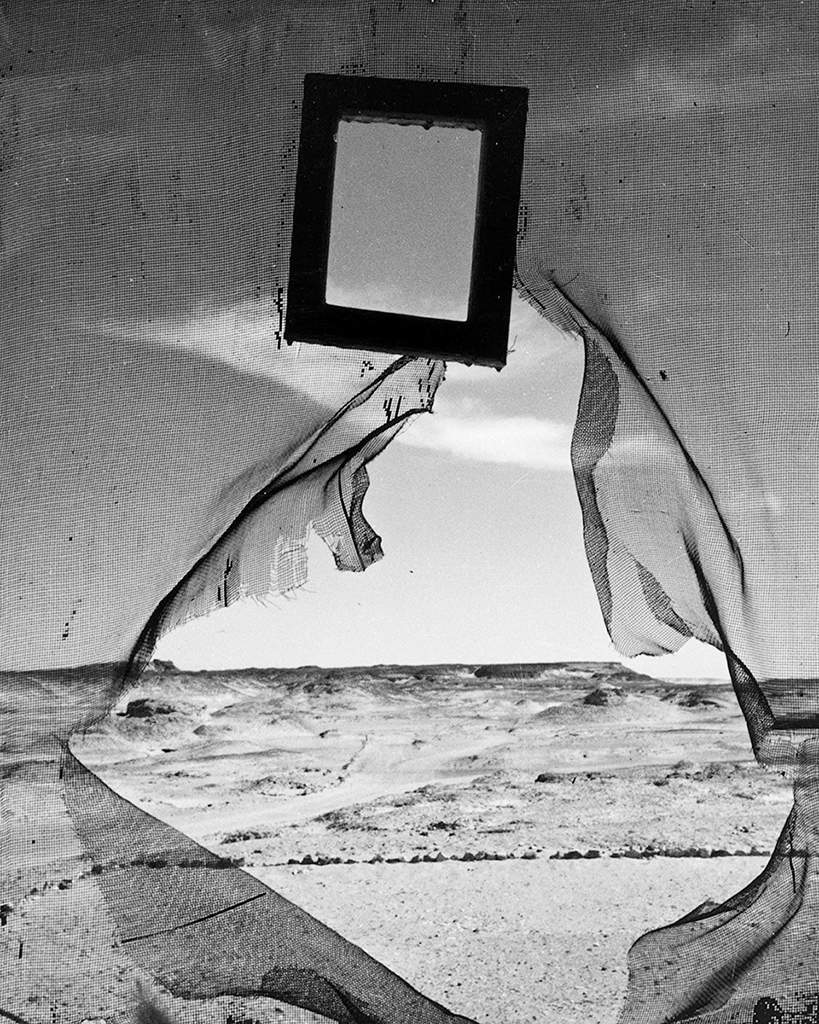

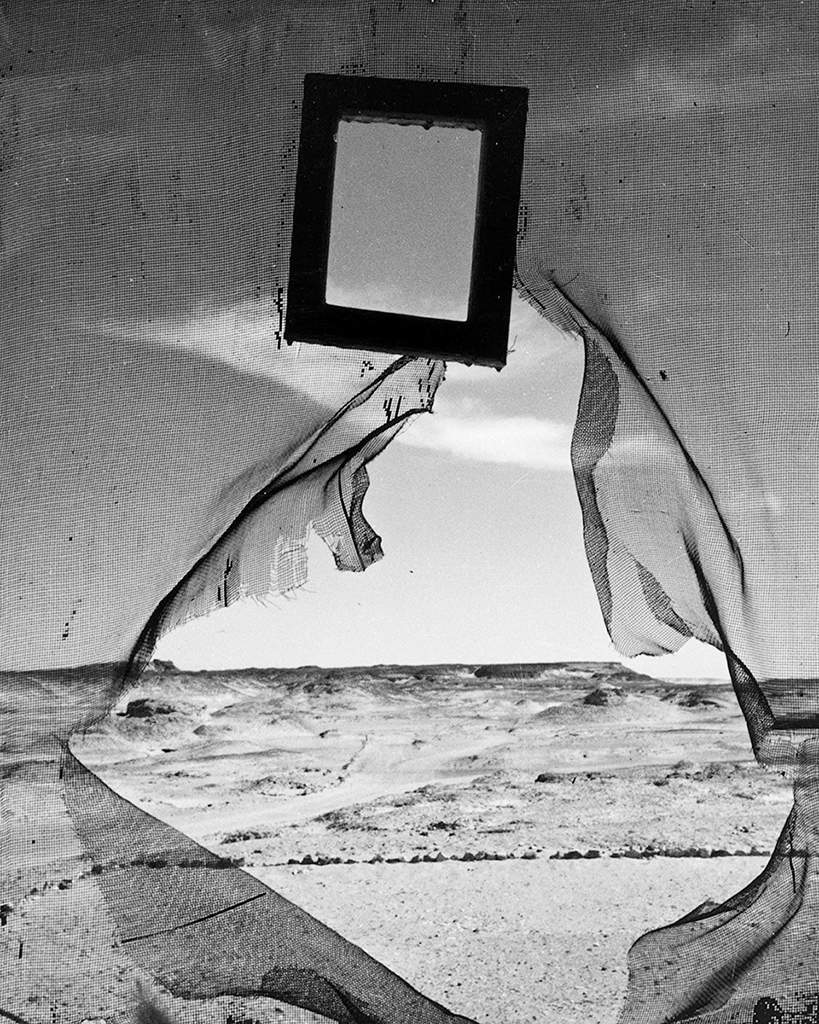

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

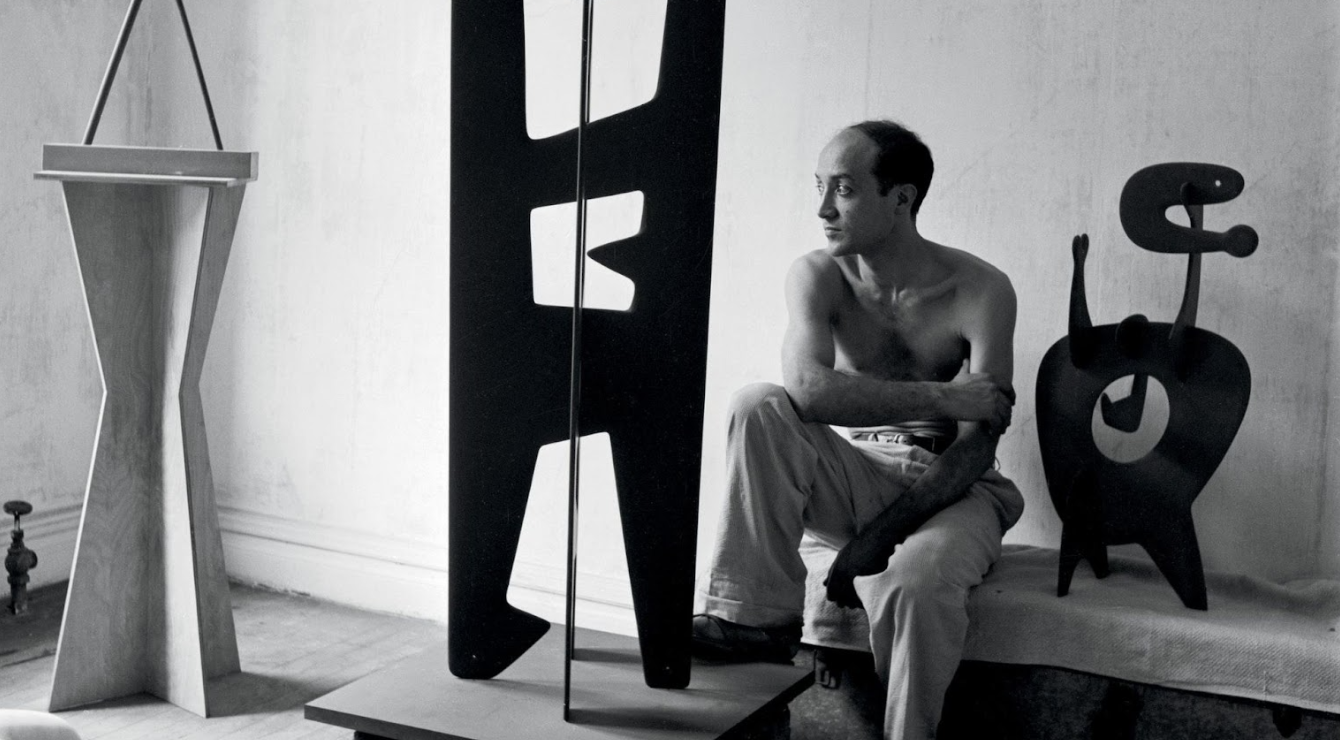

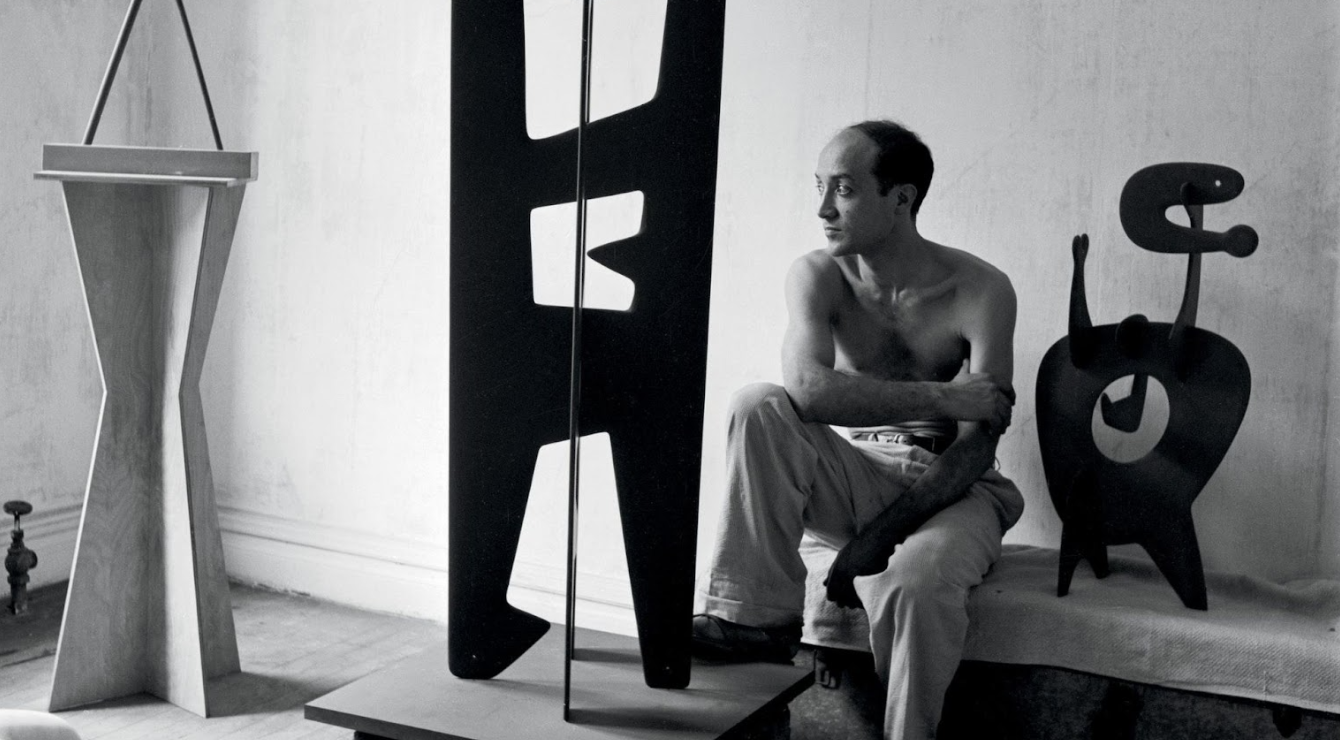

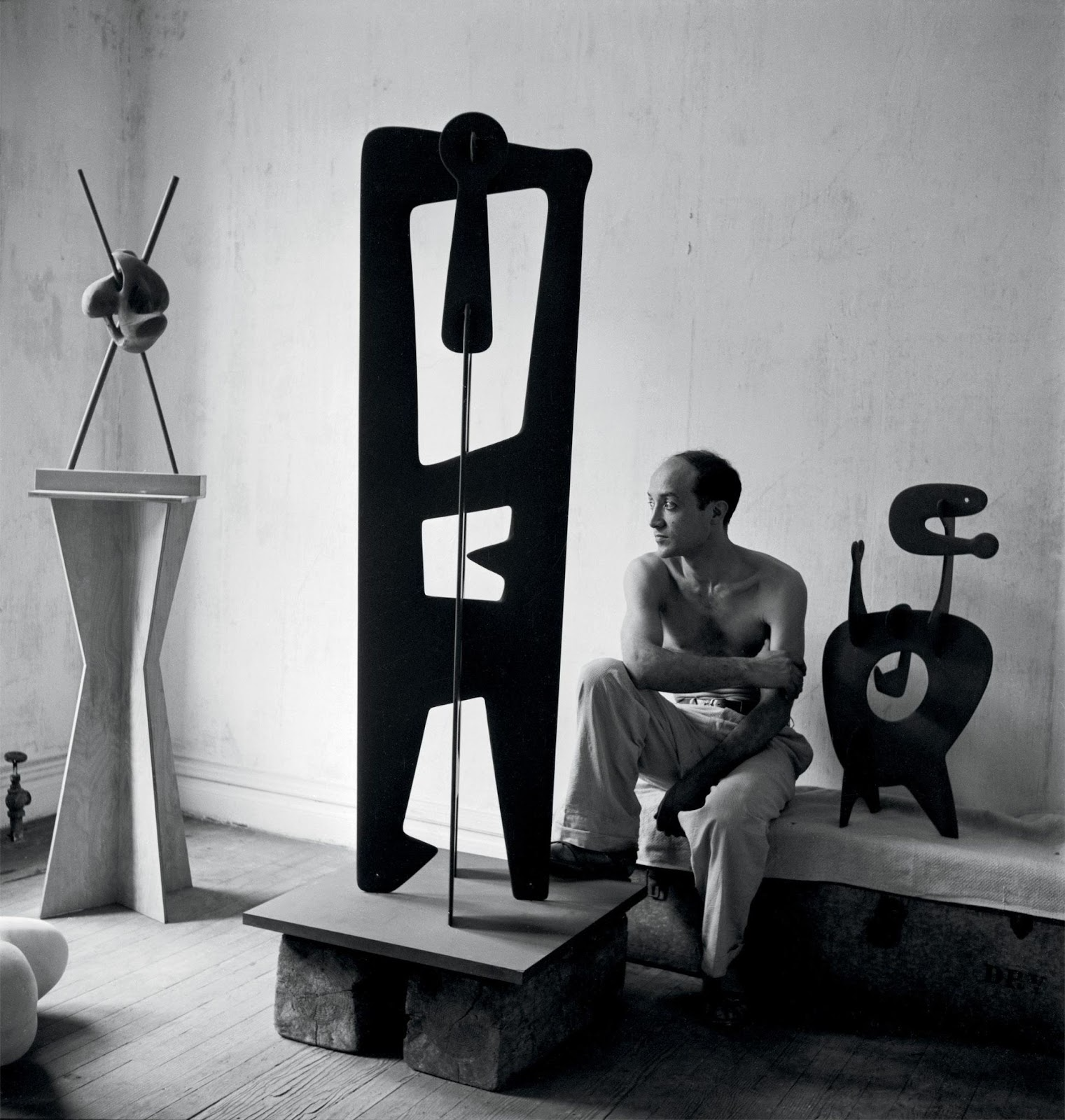

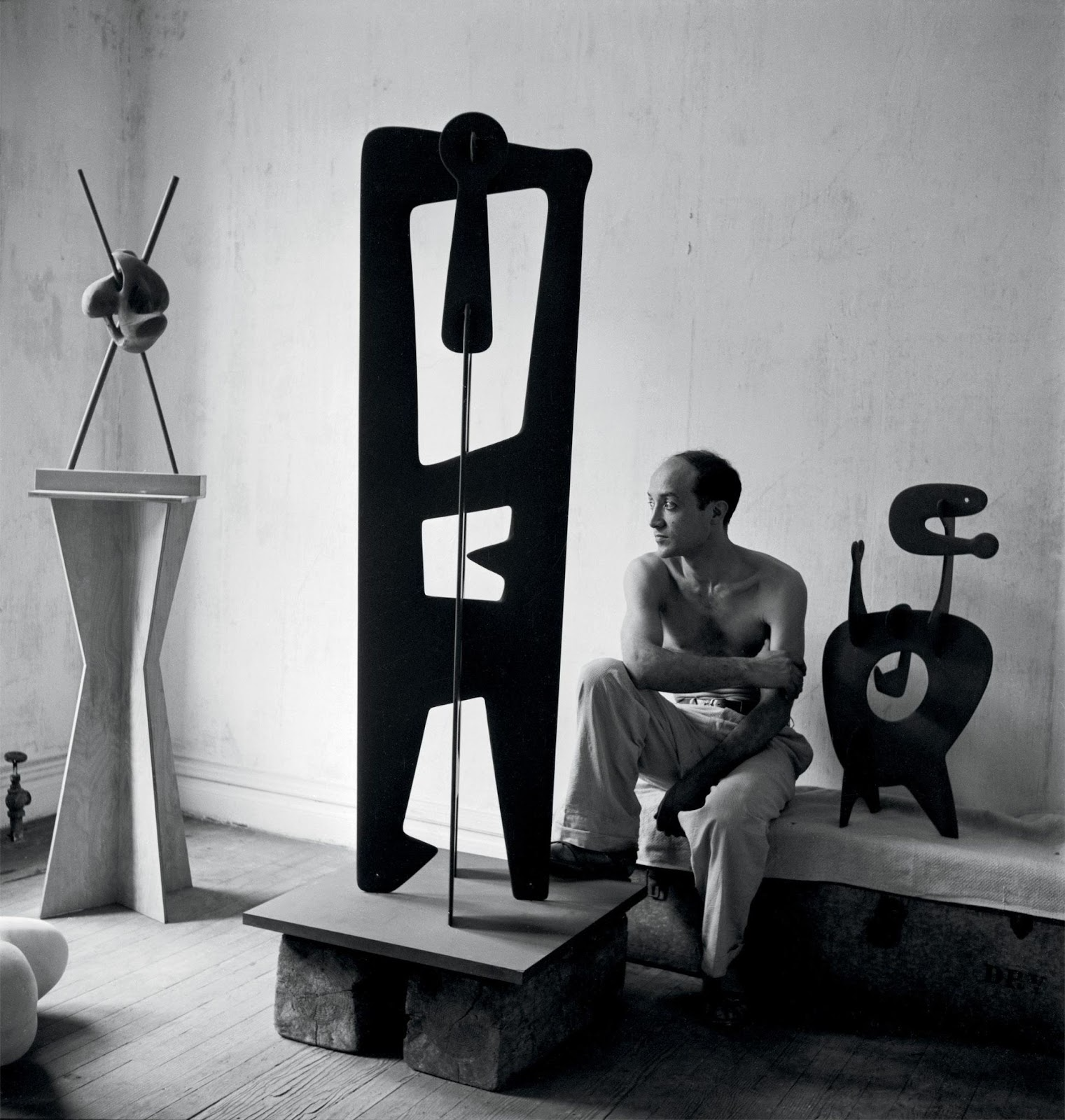

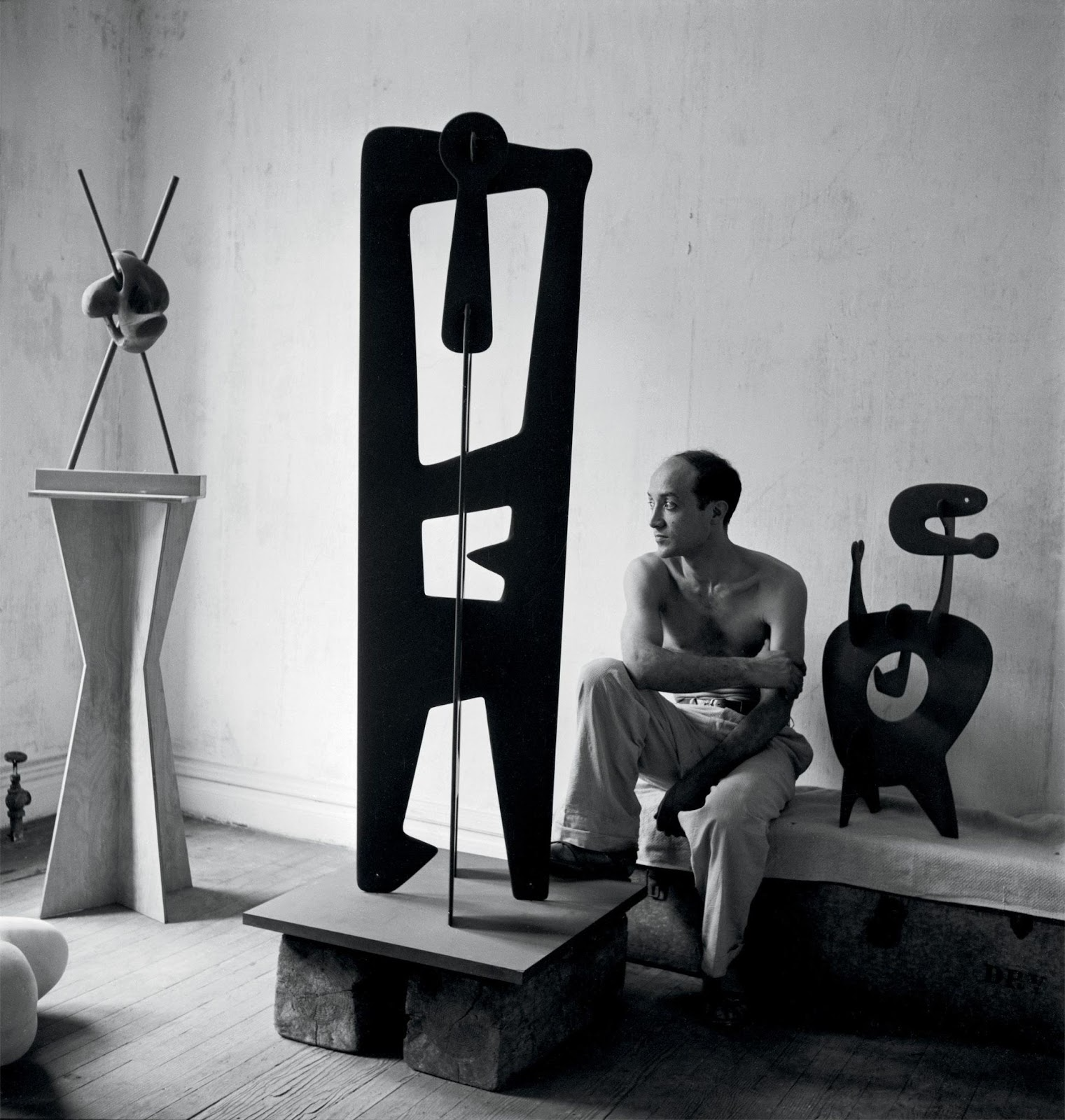

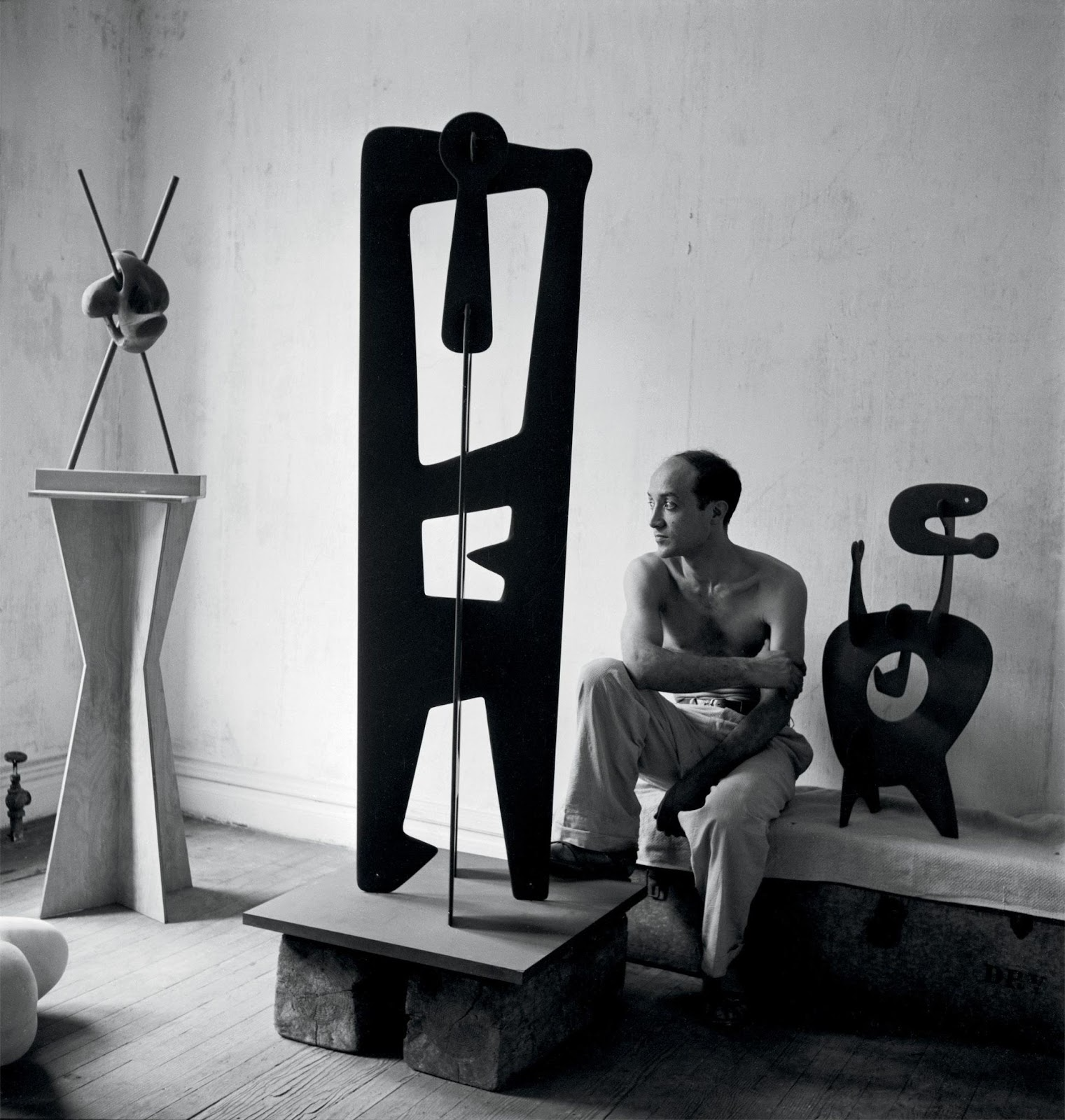

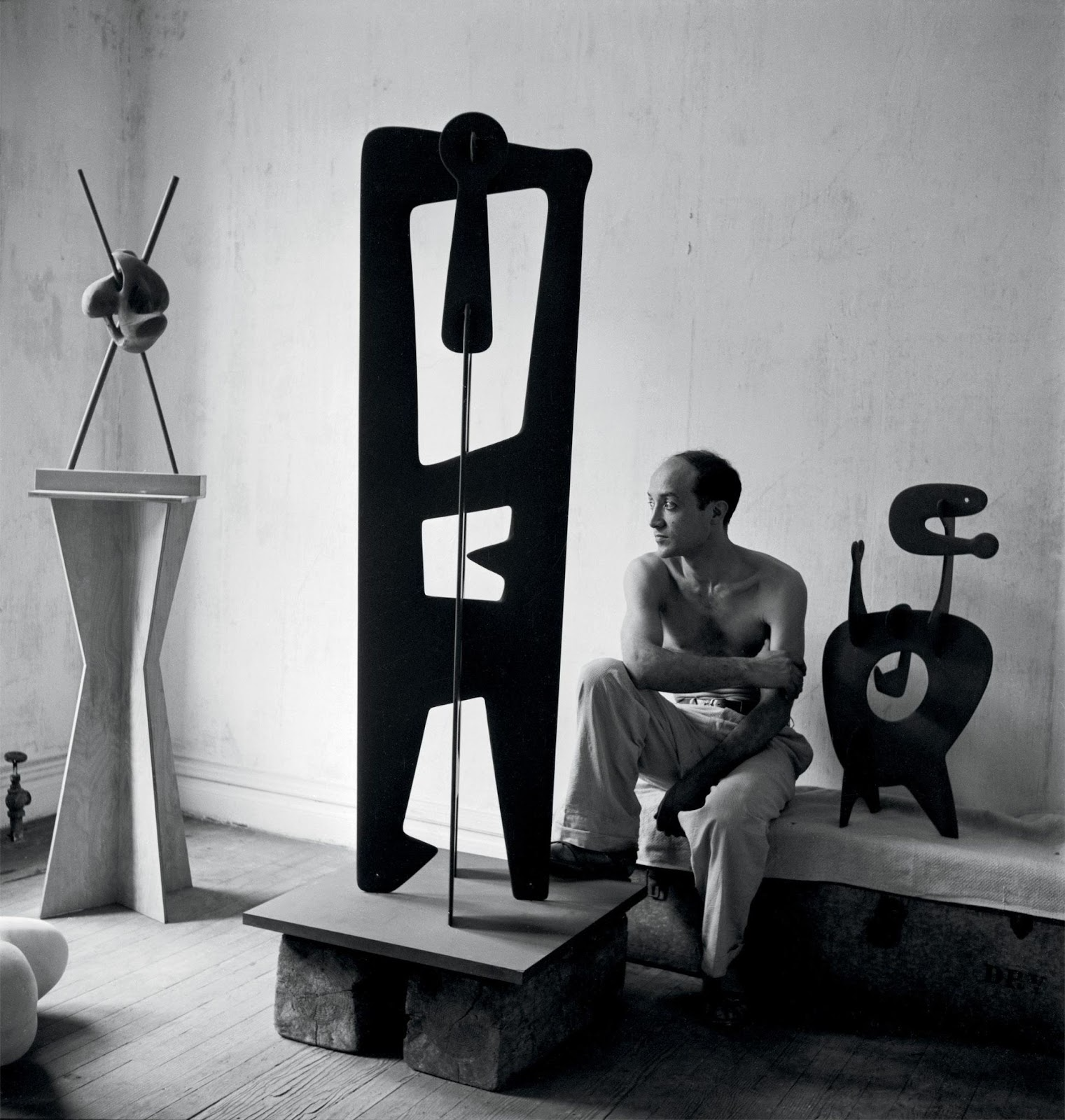

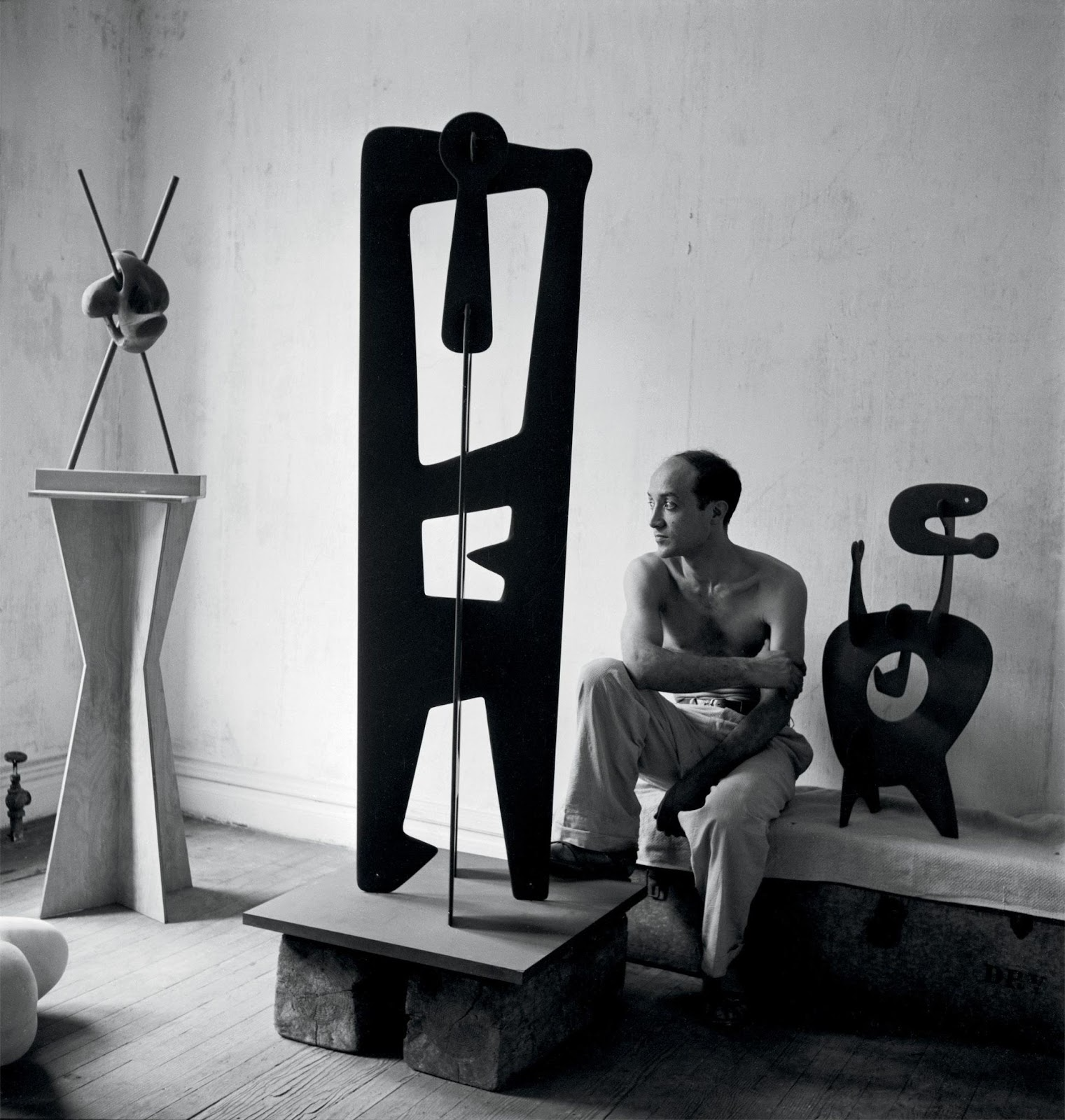

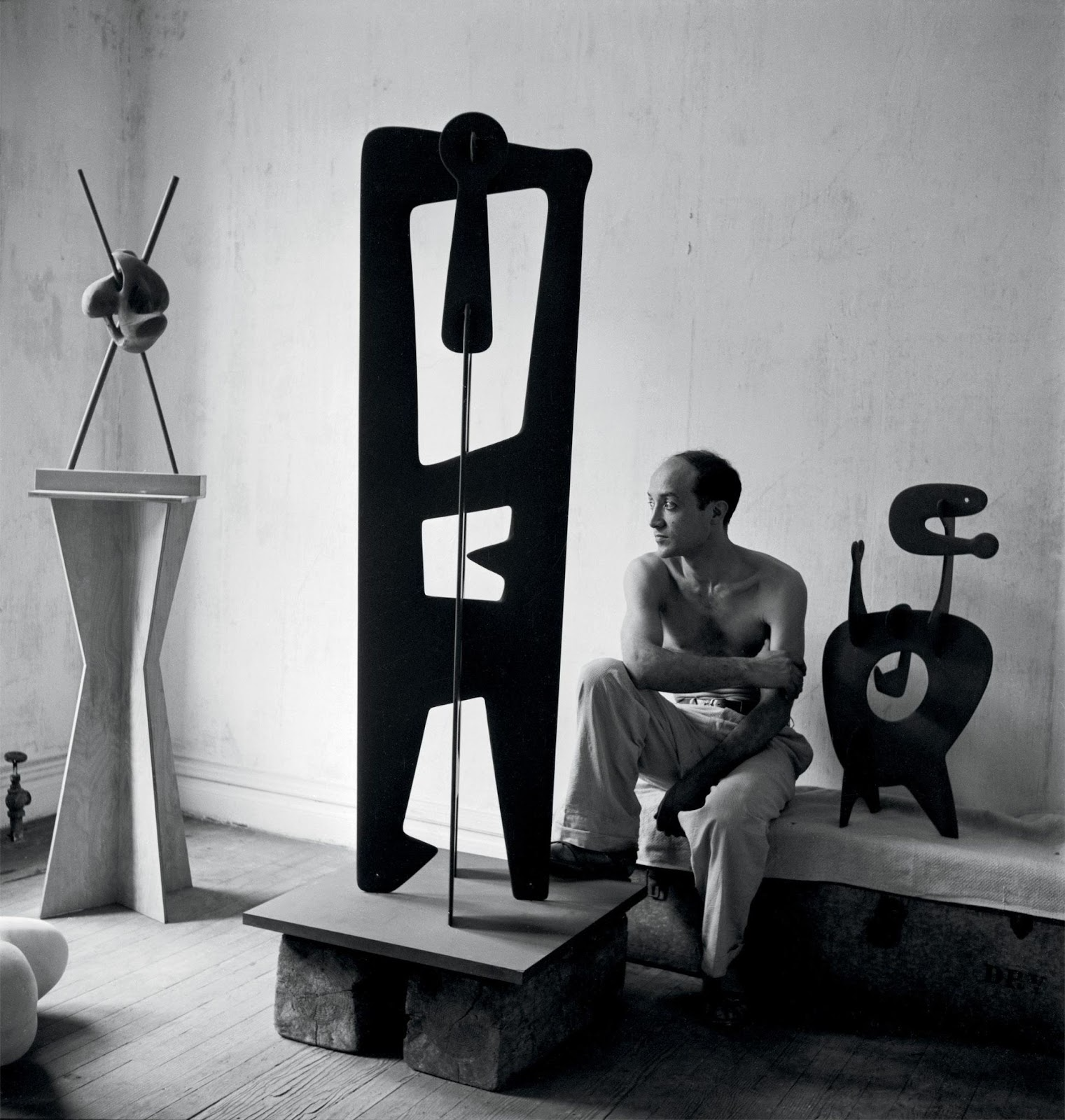

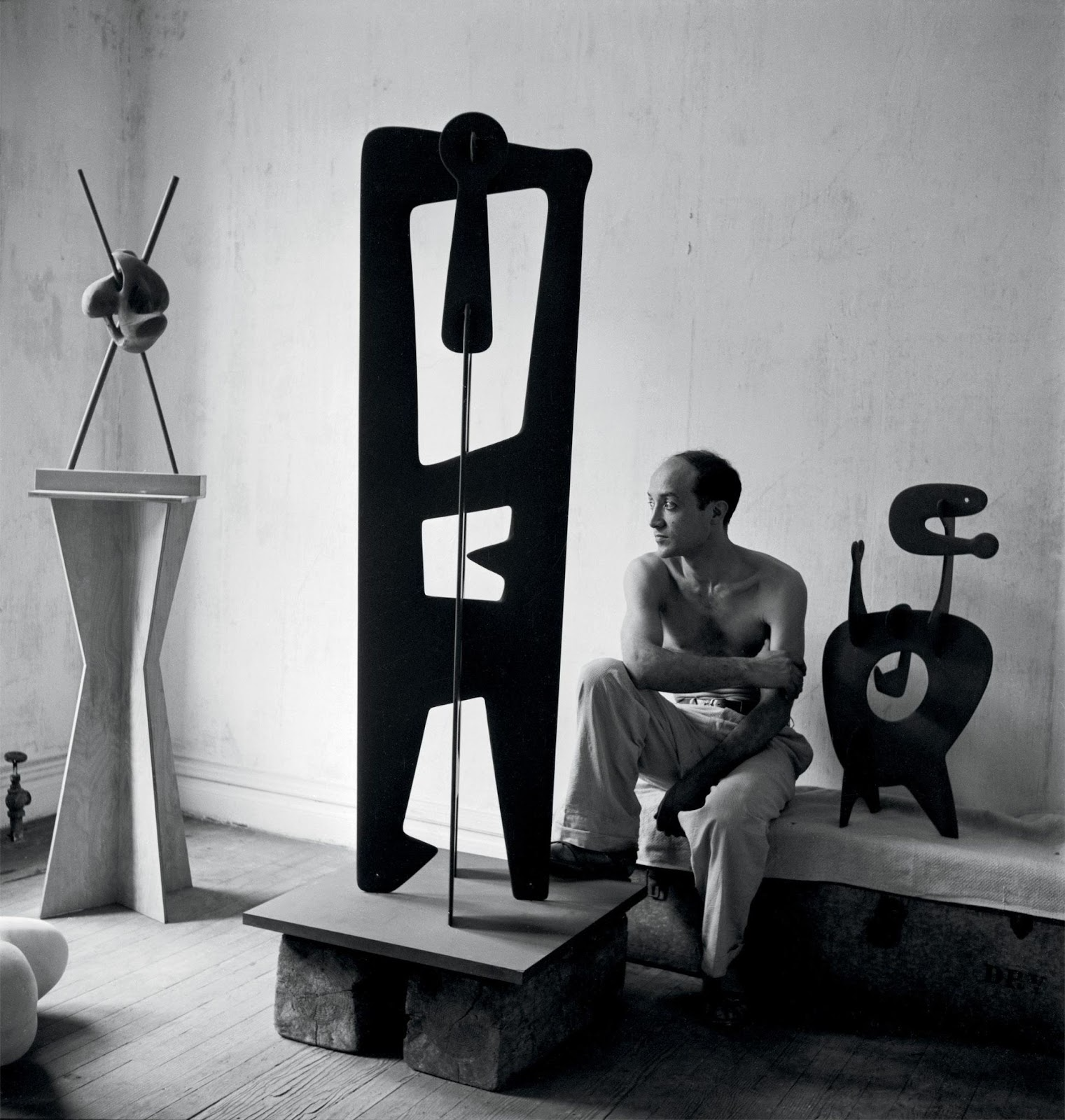

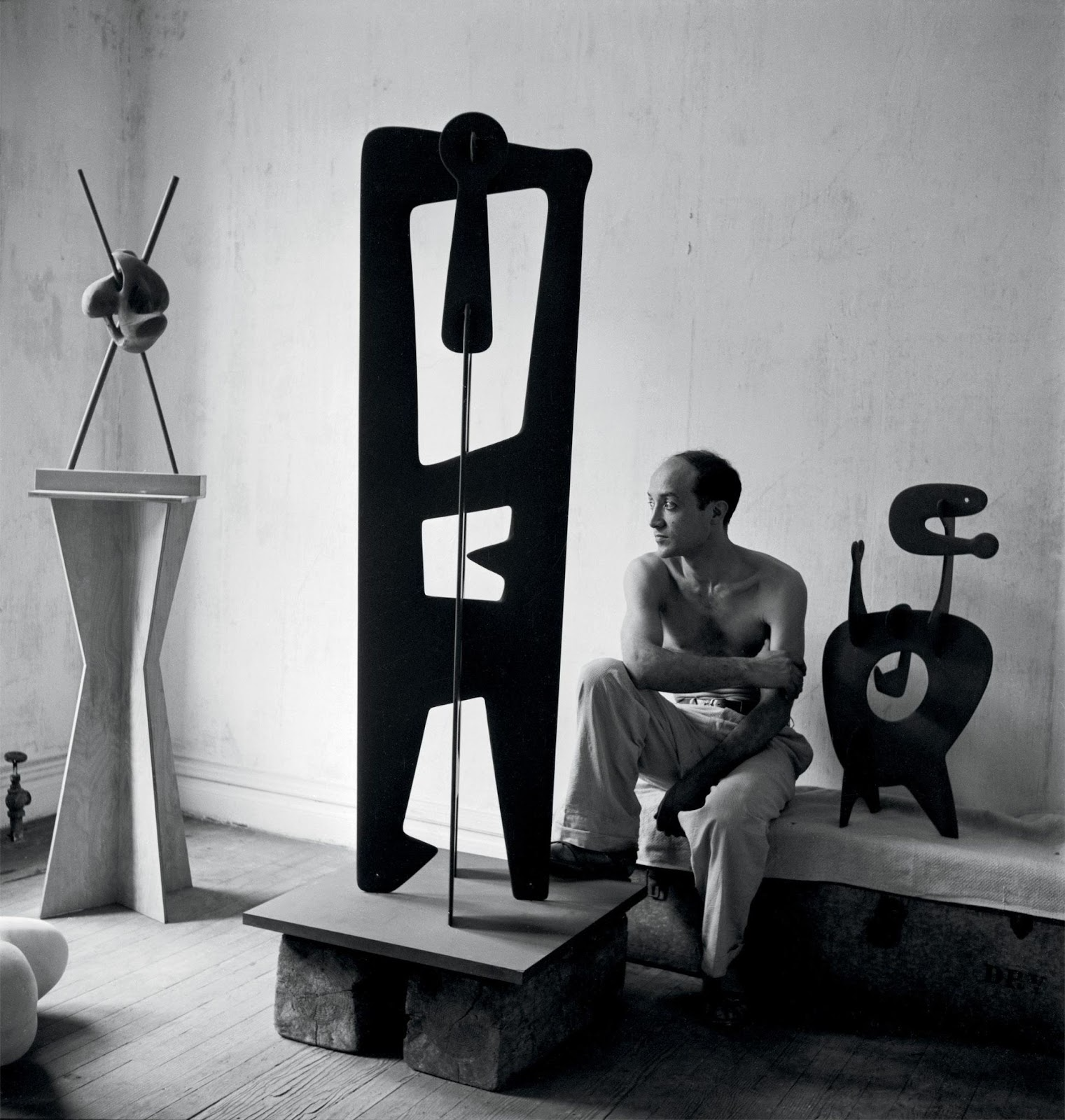

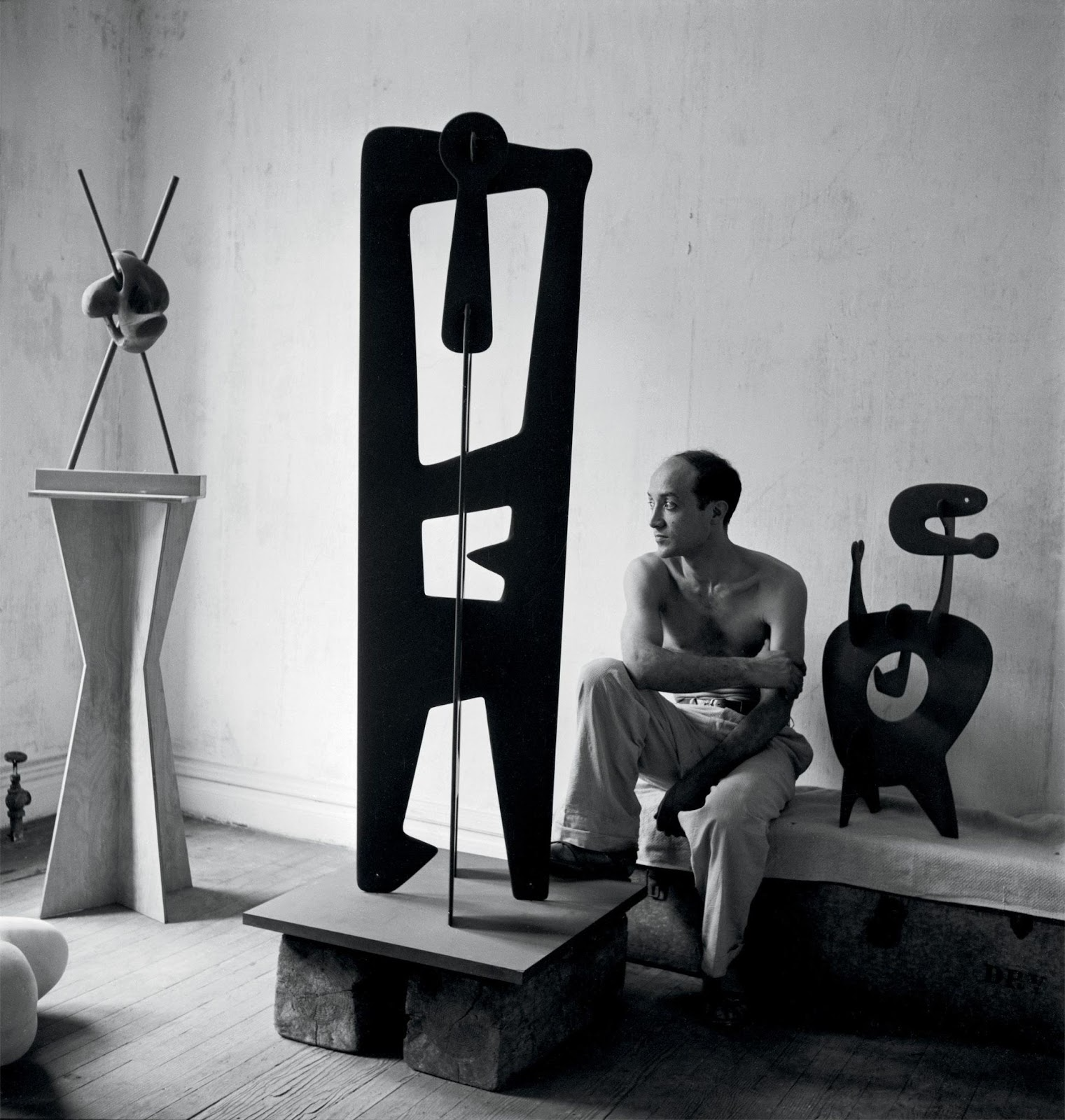

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

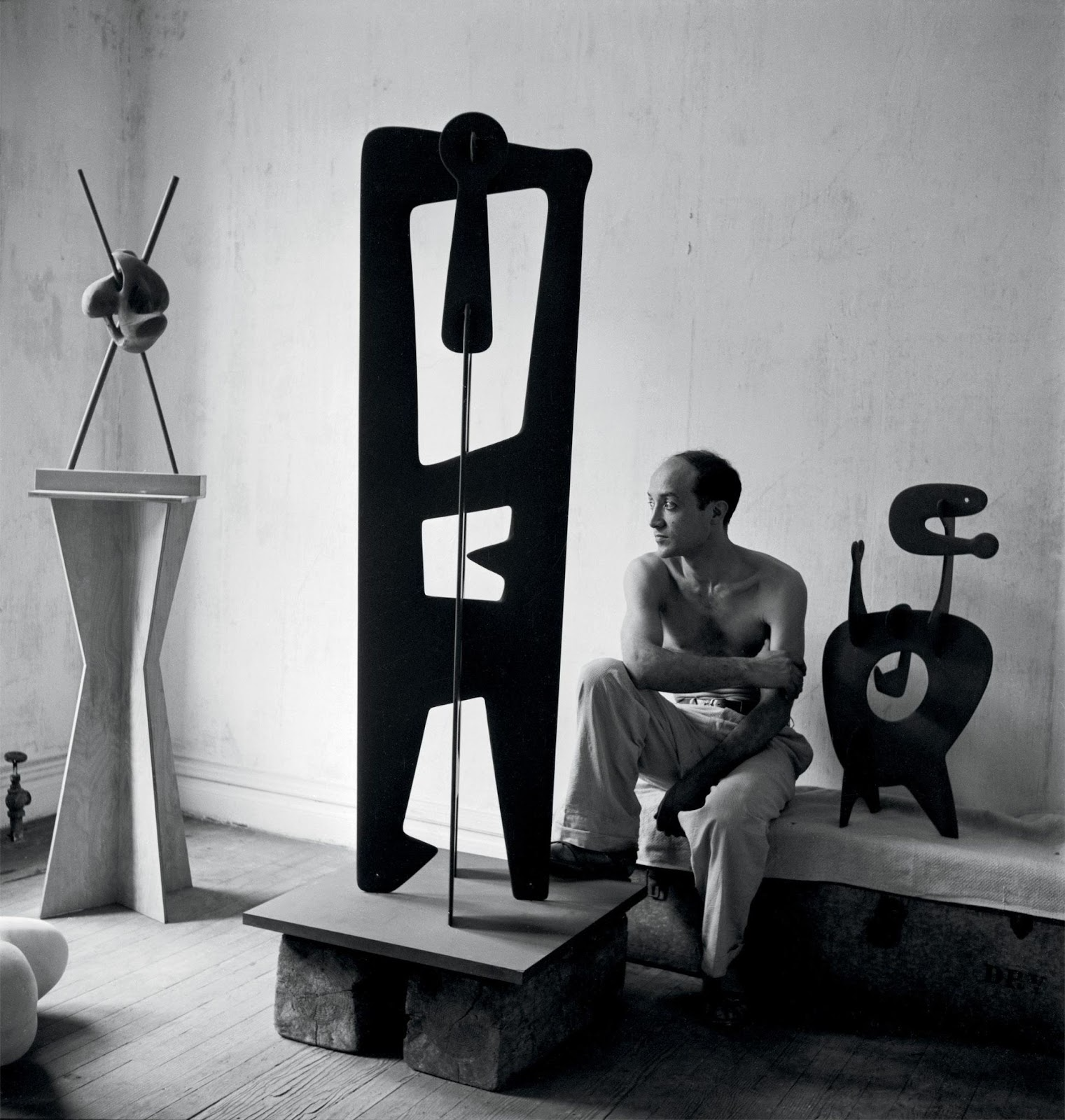

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?

I hope that people who know Lee Miller’s work will be delighted to discover new facets, and that those who have never heard of her will be surprised by how many different lives she lived… But I hope the main takeaway is her connection to other people, and how that impacted the images she made, along with her commitment to truth and sincerity through her image-making. I think the tenderness with which she photographed the women and children who were so devastatingly impacted by the Second World War really underscores the acute sensitivity and perceptiveness of Lee Miller, and underscores how powerful and relevant they are today.

Lee Miller is showing at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

From modelling to surrealism, fashion photography to war photojournalism, the entire breadth of Lee Miller’s creative life is brought together at Tate Britain for the largest retrospective of her work ever staged. We sat down with co-curator Saskia Flower to discuss the development of the show…

With such an expansive and varied body of work, was it daunting to put together a retrospective on Lee Miller’s whole career?

Oh my god, absolutely! I think the Lee Miller archives have over sixty thousand prints and negatives in their collection, and we looked through a good chunk of them - it’s almost a cliché, but Lee Miller really did live many different lives. There’s a great quote from her where she says that even if she’d lived nine simultaneous lives, she wouldn’t have had her fill; she was restless, ambitious and fearless, and always ready for the next adventure.

I think that’s really reflected in her practice as we move through the eleven sections of this show, from modelling in New York in the 1920s to her avant-garde, quite radical images in Paris, then to the heart of the surrealist artistic circles through to living in Cairo, travelling across North Africa, Europe and West Asia… Most notably, she worked as a war correspondent for Vogue in London during the Second World War, following liberation forces through Europe. However, in the final section of the exhibition, we really wanted to showcase the enduring international network of friends and artists that formed her life and were an enduring artistic subject for her. I think that where other shows have focused specifically on war, portraits, or fashion, this felt really exciting to curate because it showcases the full breadth of her work.

It was surprising to walk into the first section, which focuses on her modelling work in front of the camera rather than behind it…

Absolutely, that’s something that Hilary Floe, the senior curator on this project, really championed - modelling has historically been seen as quite a passive action, where credit is often given solely to the photographer. What we wanted to do in this show was position Miller’s modelling career as a real collaboration with her photographers; she was trained in dance and lighting before she was a photographer, and really knew how to perform for the camera. I think her unique position, both in front of and behind the camera, allowed her to create very tender, humane portraits of her friends, as well as victims of the Second World War and its impact on citizens. I think her comfort on both sides of that artistic process really allowed for very powerful and poetic images.

And it really reinforces her later photographic portraits of other artists as collaborations…

Exactly, yeah - by including that first section of her modelling, and two sections in this ‘Artists and Friends’ series, these build a portrait of a sprawling international network. It becomes a story about collaboration, about the fluidity of authorship and bringing a sense of the artists’ personalities to the fore. You’ve got these images of Joseph Cornell posing with some of his assemblages as if they’re part of his own head, and these Noguchi portraits, which are real favourites of mine… They were both at New York’s Art Students League in the 1920s; then, twenty years later, she returned and was reunited with Noguchi to create these wonderful portraits of him with his sculptures. They really draw out the corporeal quality of his abstract sculptures by posing him bare-chested beside them, and there’s a real intimacy there, a comfort not just from her experience as a model but also from her immense gift of friendship.

So it’s not just contextualising her, but also keeping the focus on her work?

Definitely - the key driver of this was positioning Lee Miller as an artist and making sure that this was an image-led project. With so many images to choose from, Hilary and I asked ourselves, at every stage, whether it serves her as an artist.

And that extends to the inclusion of extracts from her post-war essays, which are on the wall throughout - how important was it to portray Miller in her own words as well as through her art?

Oh, so important! Lee Miller was not the only woman photojournalist, but she was quite unusual in being both a photojournalist and a journalist, making photos and writing essays at the same time. In fact, she wasn’t trained as a writer, but when she arrived in Europe as a war correspondent for Vogue, she found herself quite gifted. These essays that she wrote were extraordinary, and we had an amazing time going through the manuscripts, which were eventually chopped up by her editors in London and New York and made into these articles… Bringing her voice to marry text and image felt really important, to really put her voice at the centre and champion her as an amazing journalist, as well as an artist and photographer.

It’s also such a unique creative path to move from Surrealism to war photography, which is largely defined by its realism… Do you see a continuity between these disparate periods of her work?

Yeah, this is a great question, and one we kept coming back to, because we do need to consider what it means to have war photography in an art exhibition… By the time Miller was working as a war correspondent, she had two decades of experience as a photographer and had honed her craft. So, by the time she arrived in Europe to document the war, she was already naturally very skilled as a composer and as an image-maker, which allowed her to create these really enduring, powerful images. It’s also important to consider what it meant to see these images in a fashion magazine; Vogue was a monthly magazine, so it’s not like these images were going into the newspaper the next day. I think her many years of working as a fine art photographer, as a fashion photographer, and as a portraitist gave her an amazing platform from which to create these images, which really resonated with Condé Nast’s audiences.

Experimentation in photography is such a hallmark of Miller’s early work, for instance, the solarisation effect she worked on with Man Ray. How do you see the legacy of Lee Miller in the development of photography?

It’s certainly true that Miller was always interested in new technologies and was really inspired by advancements in engineering and technology. She was the child of an engineer, raised with the idea of taking things apart and putting them back together again, and she was a very technically proficient printmaker. But I think it’s hard to say what her legacy is, because that’s for the many generations of artists who have followed her and been inspired by her to say. From my perspective, her legacy is one of fearlessness, of resistance to being defined by other people’s expectations or definitions of how to live. I think she was extraordinarily open and free to live the way that she wanted to, on her own terms, and that played out both in the technical developments of photography as a medium and also in the different kinds of images she was making.

The disillusionment she felt after the war forms a major part of the exhibition. Is there anything you hope visitors can take away from these works?