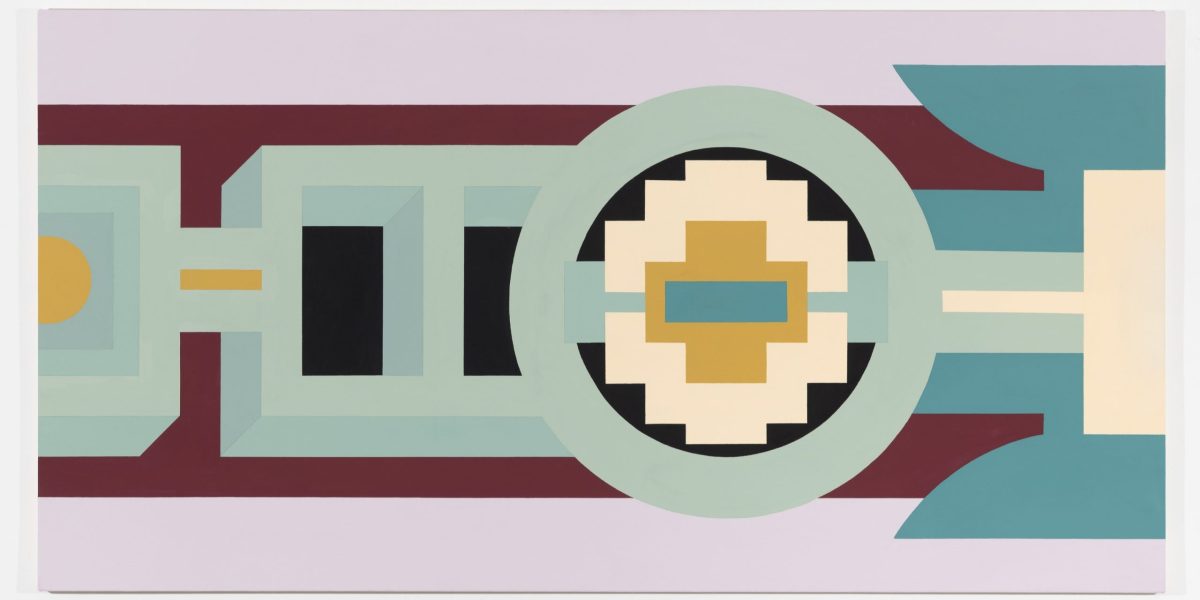

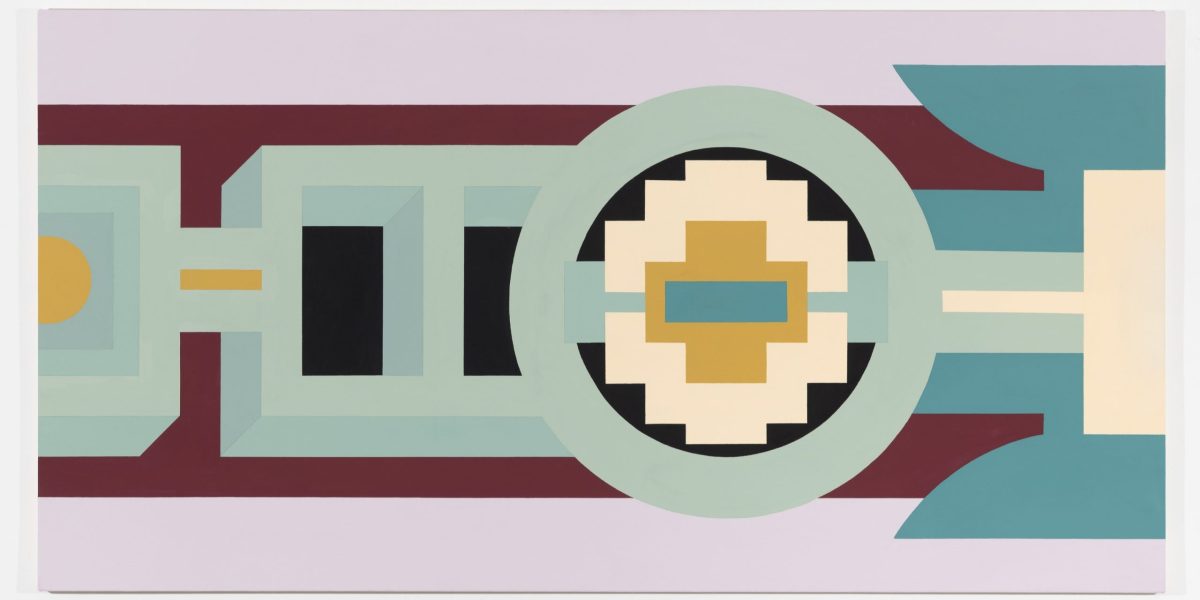

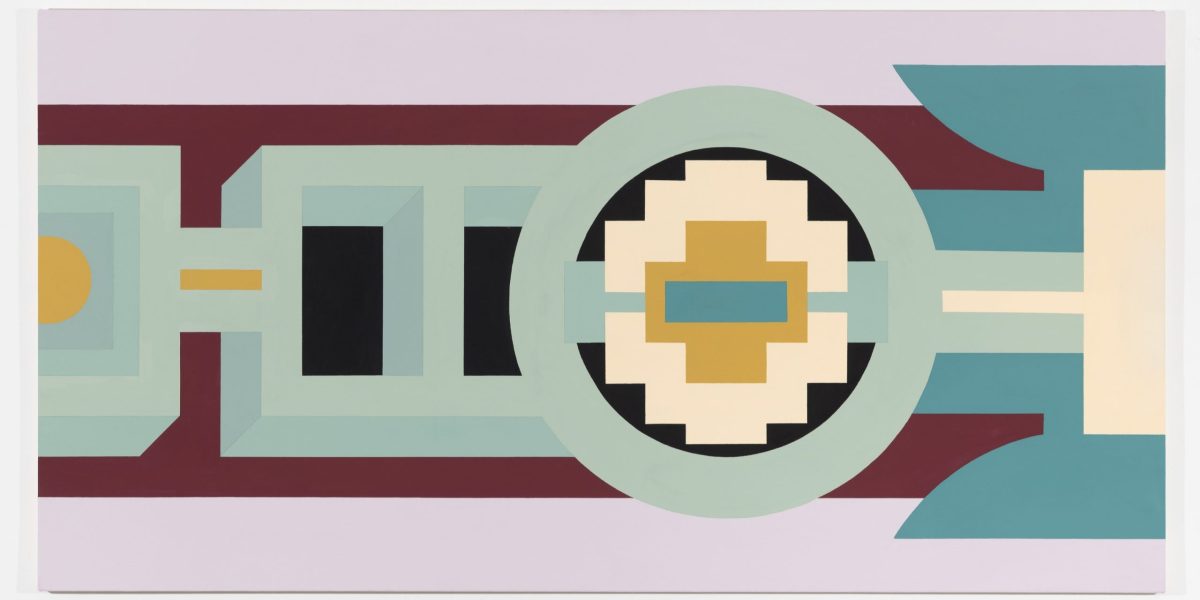

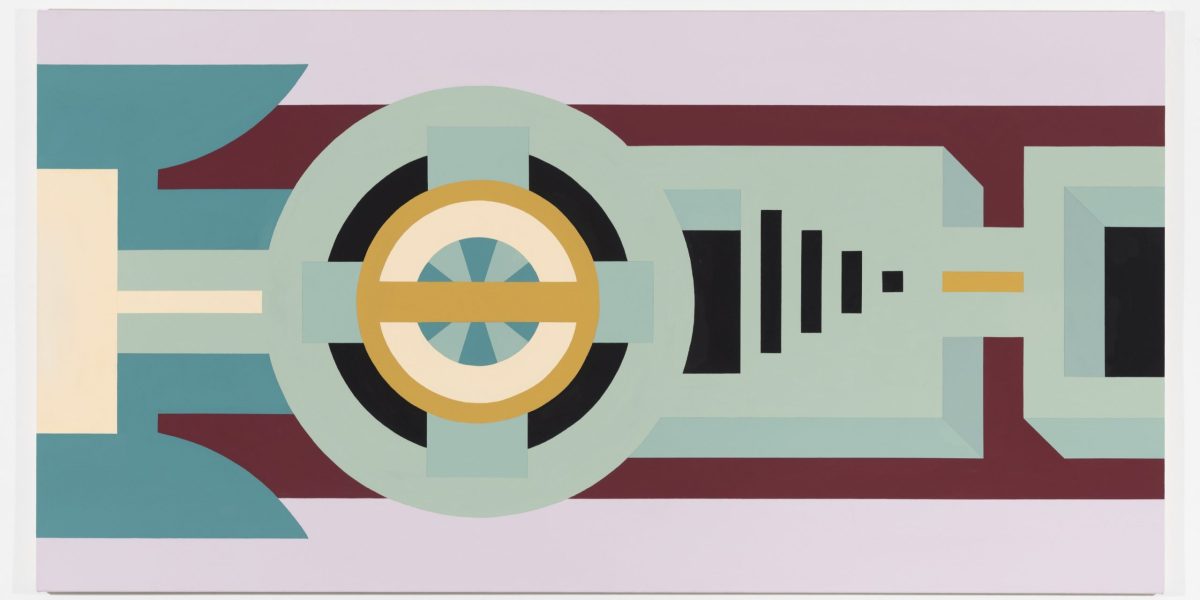

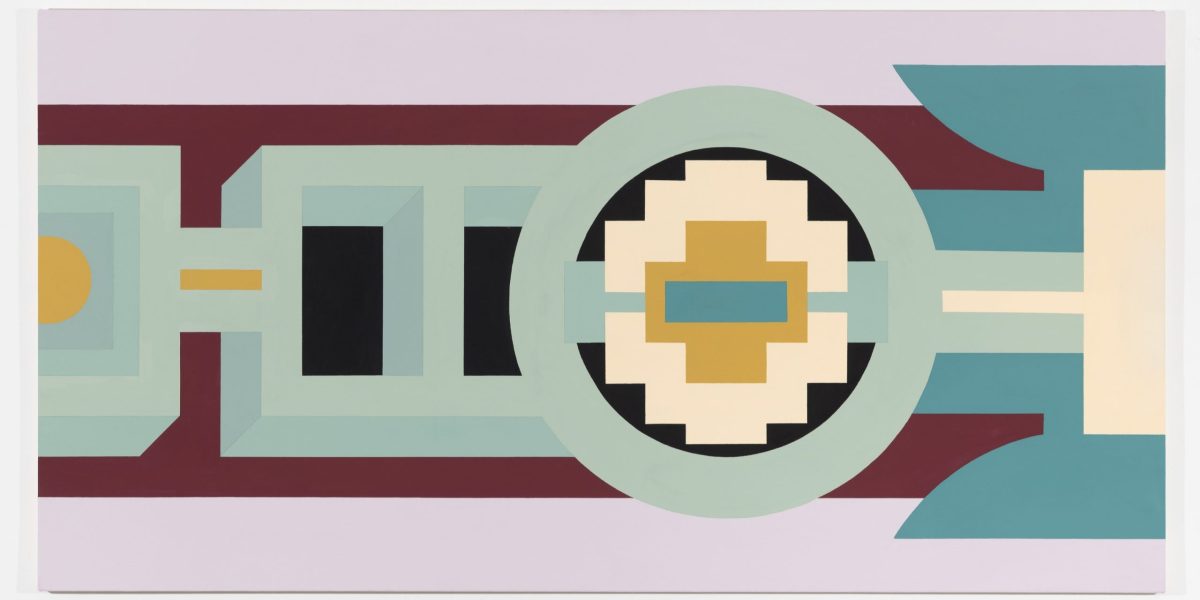

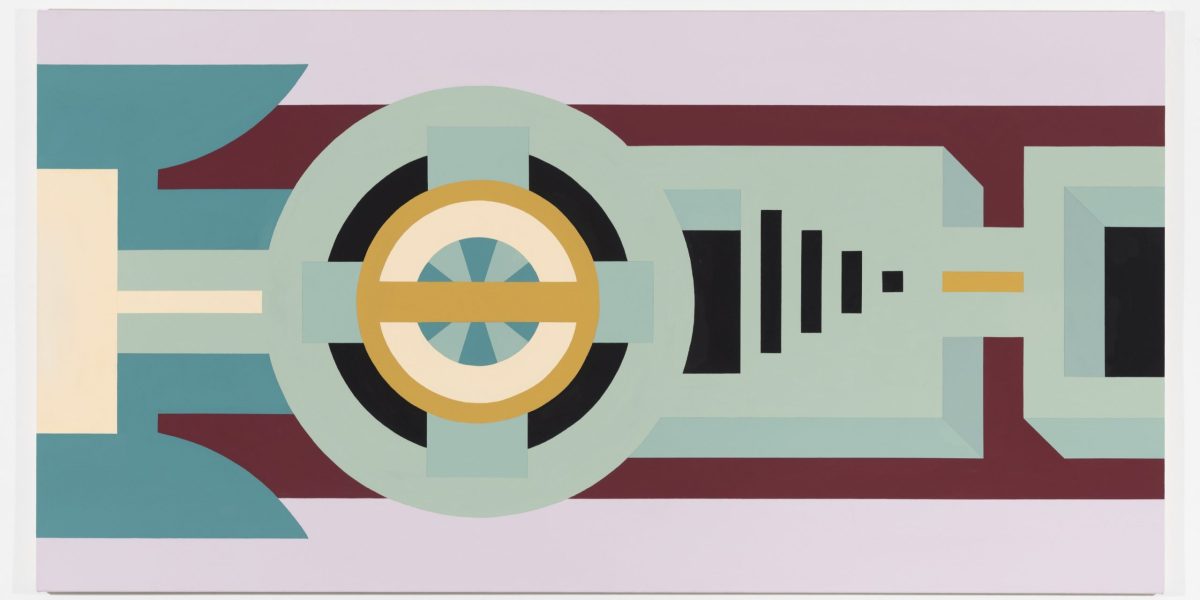

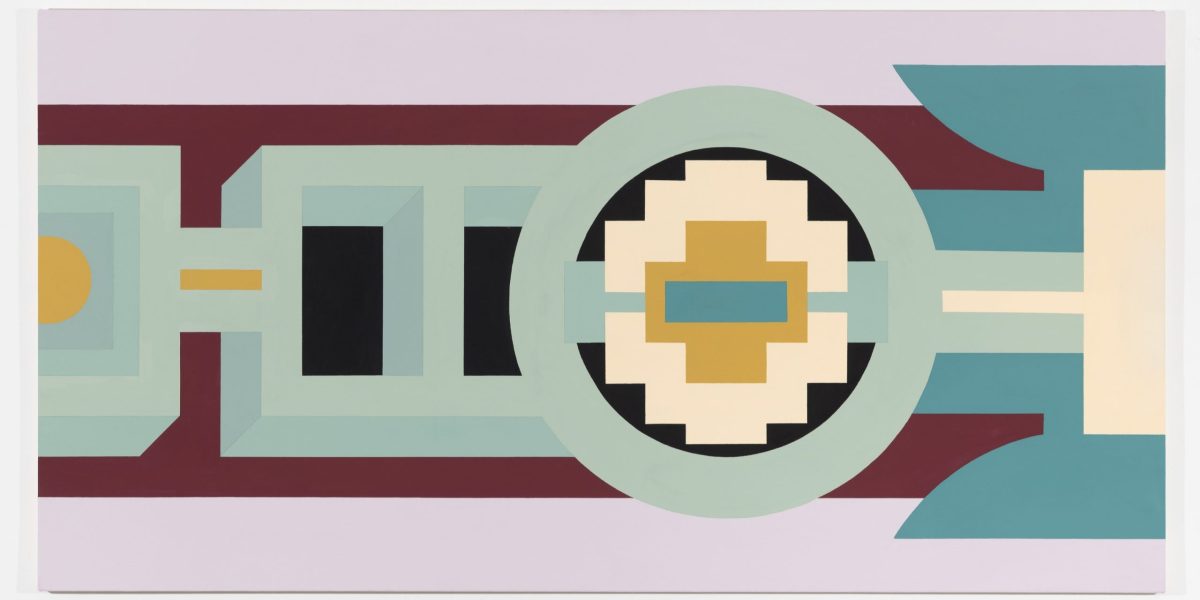

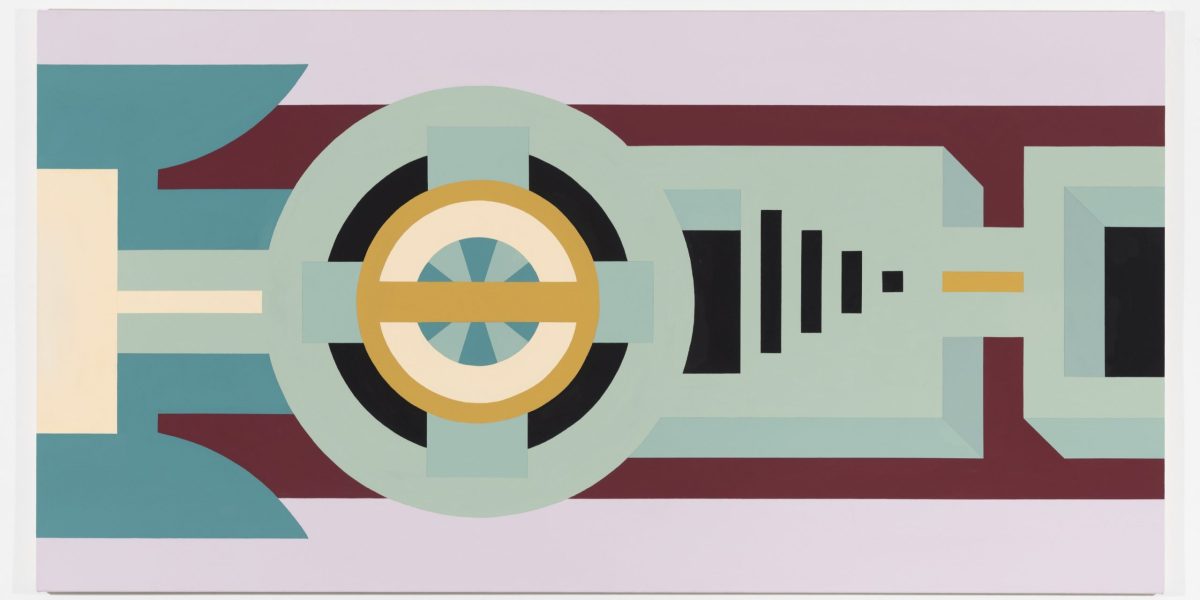

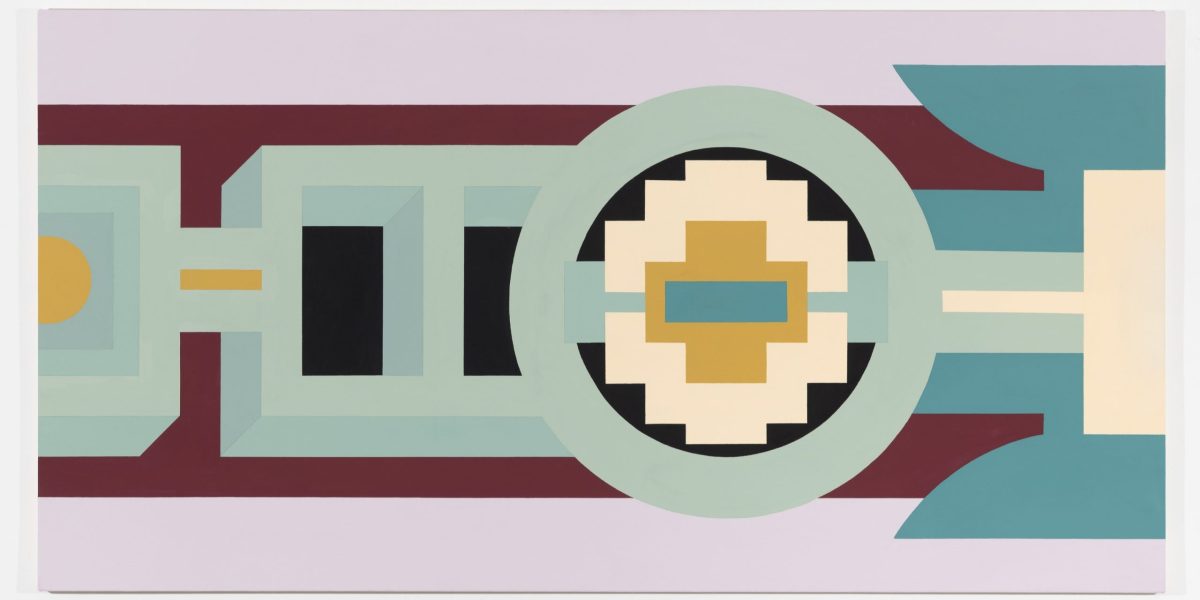

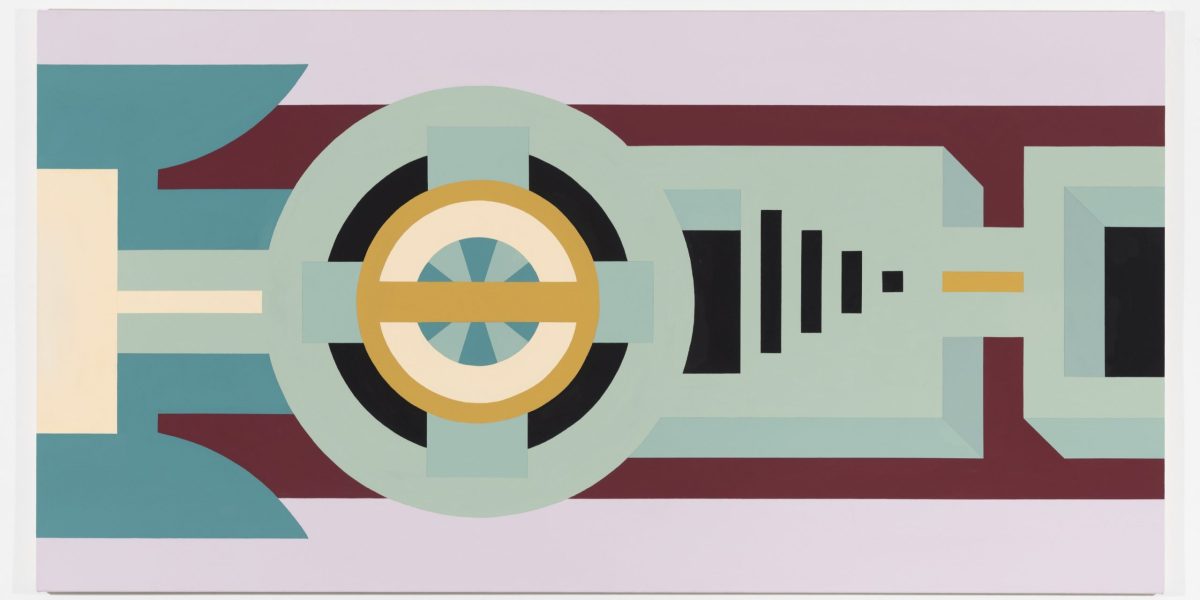

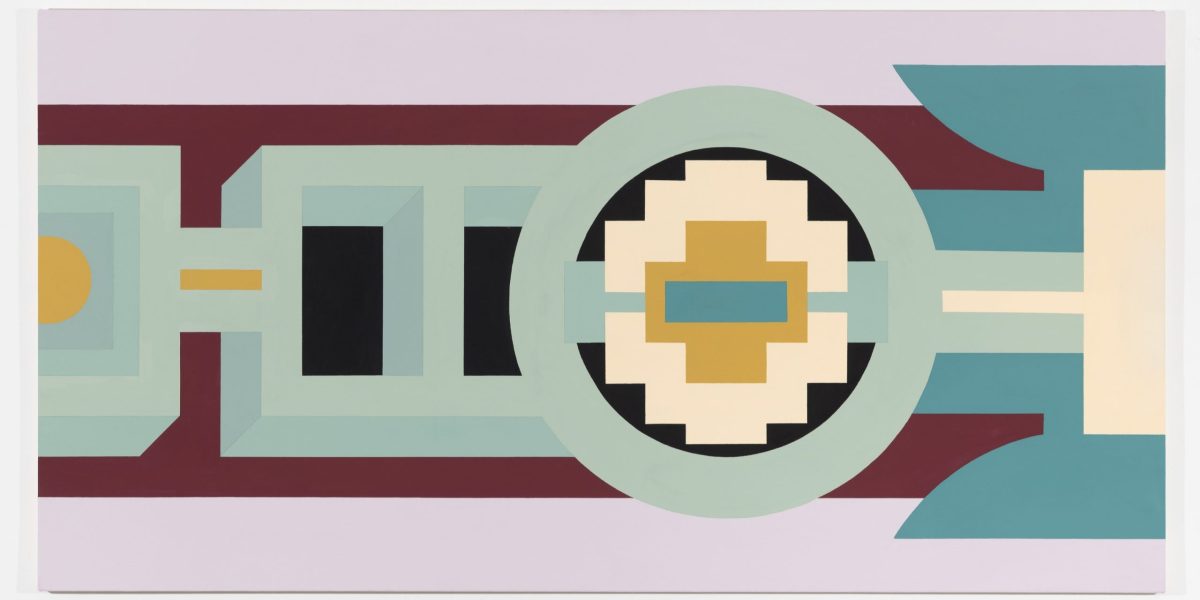

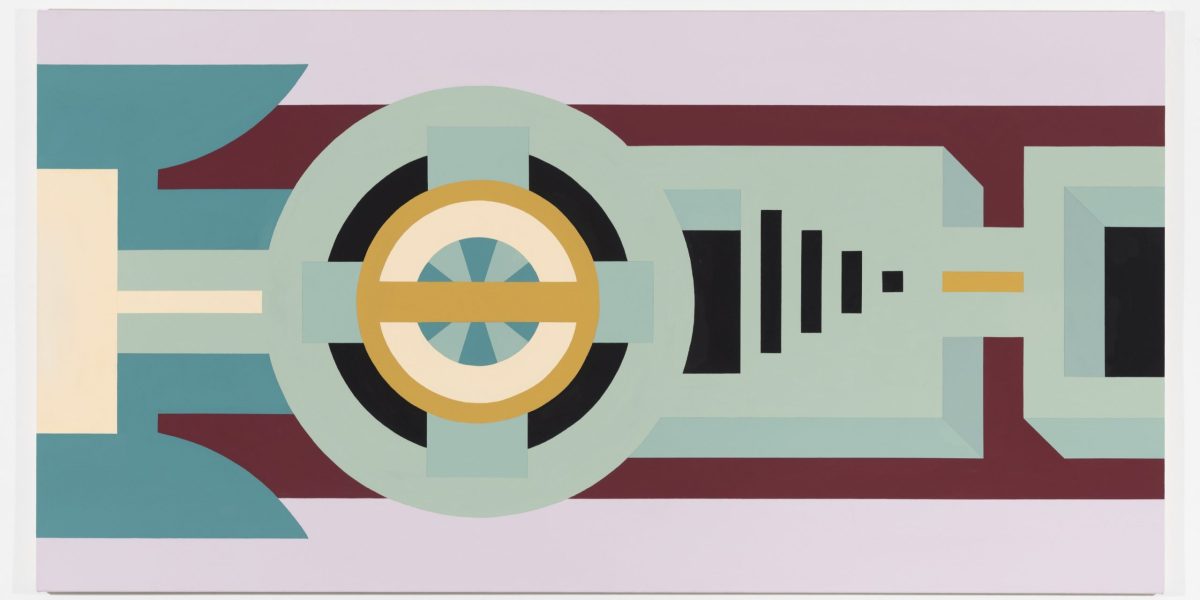

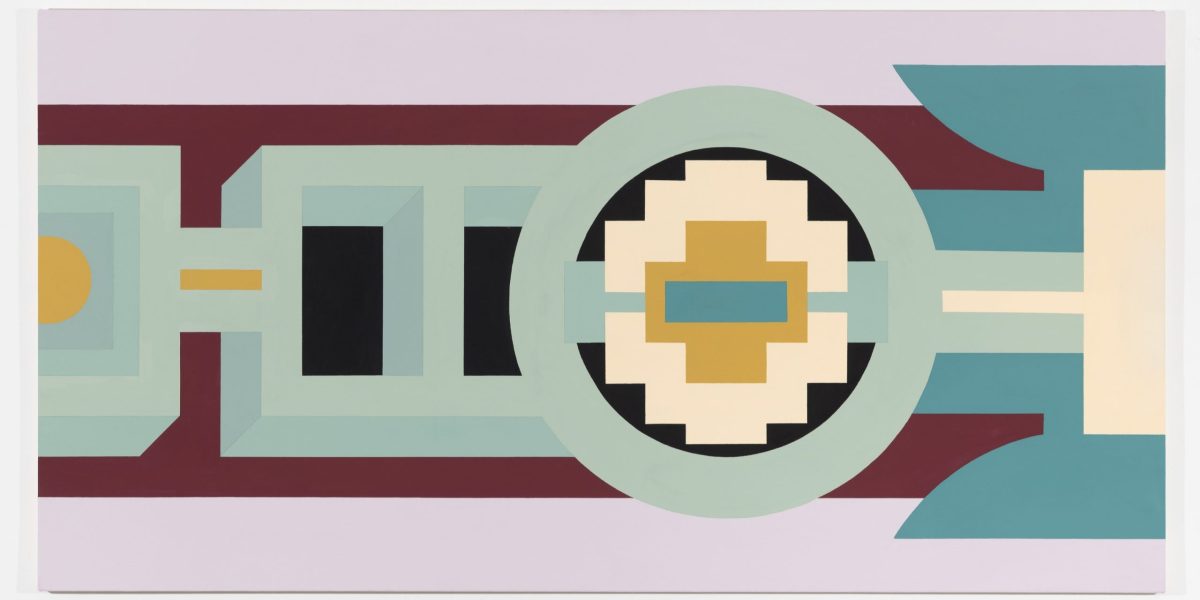

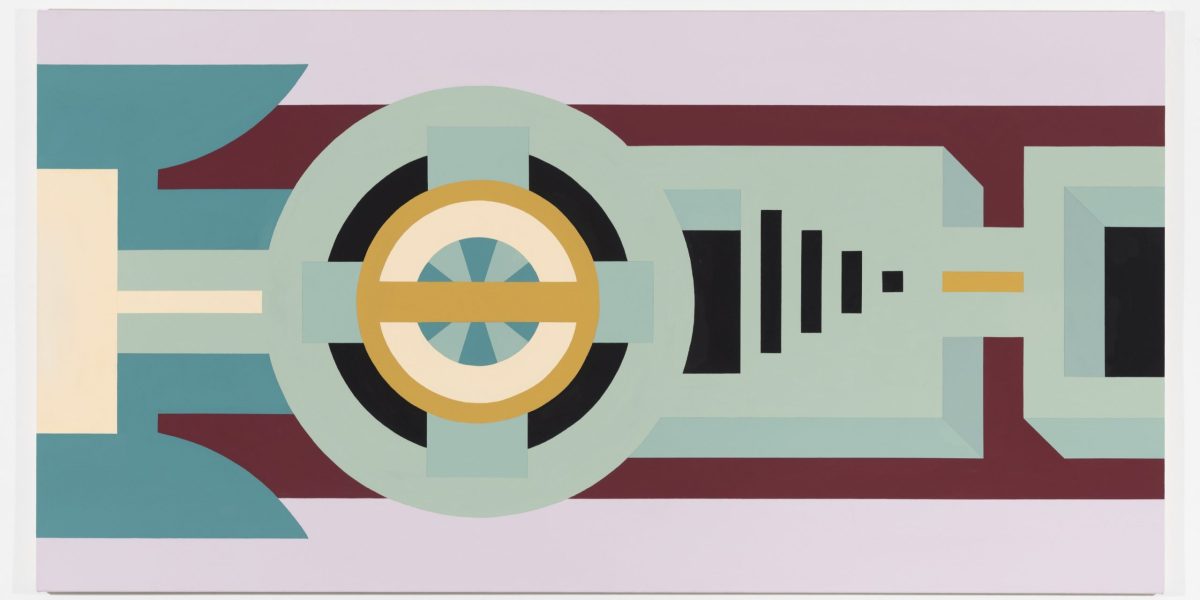

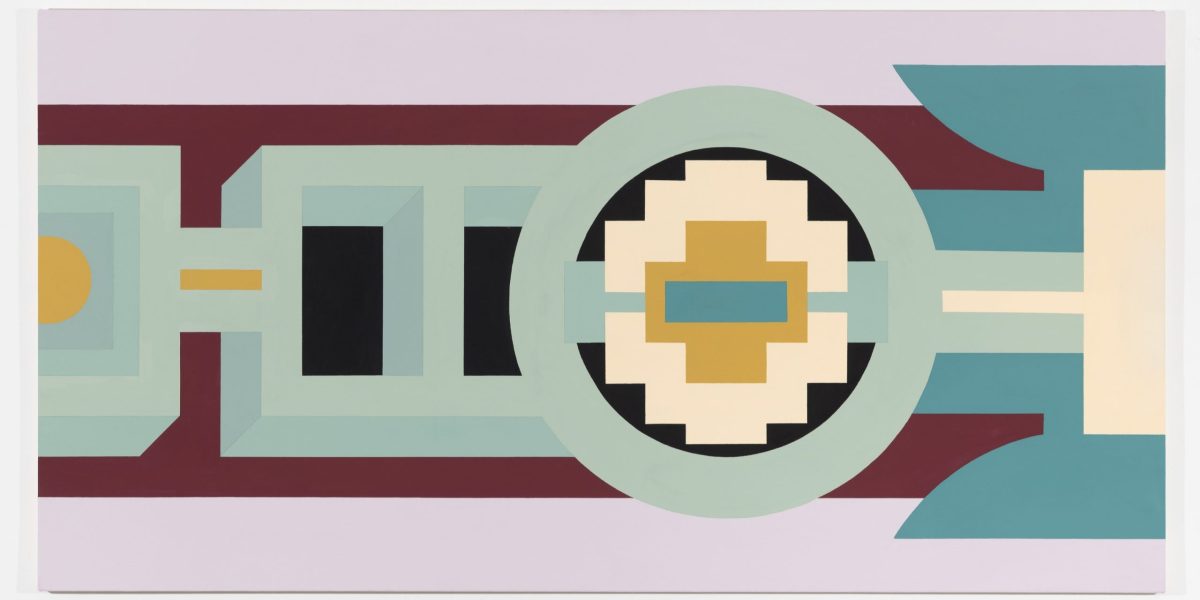

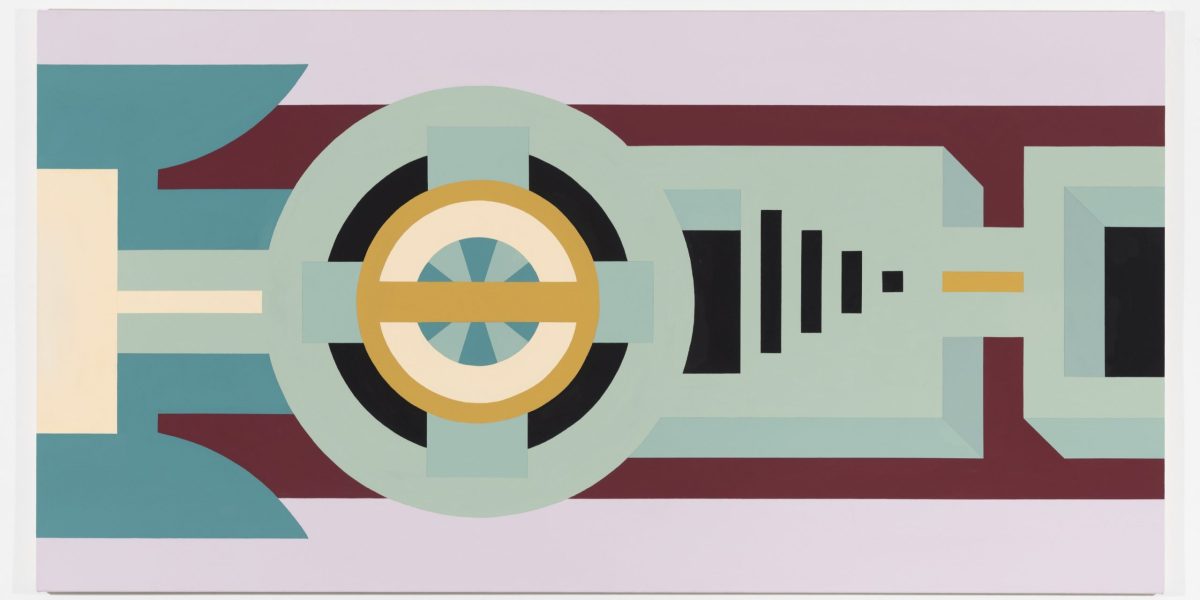

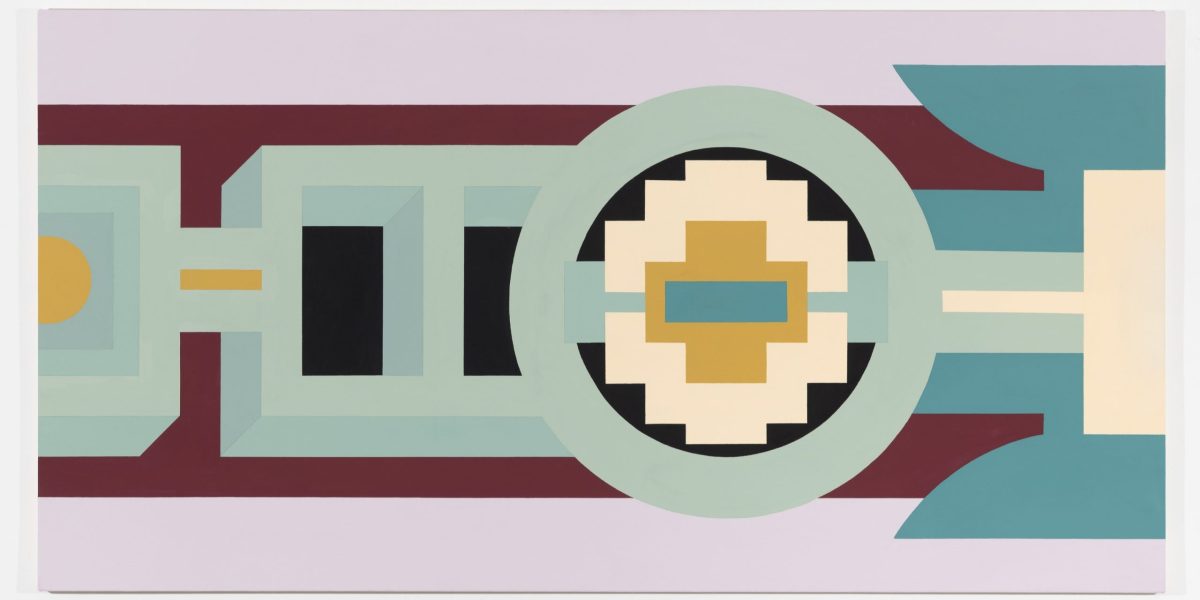

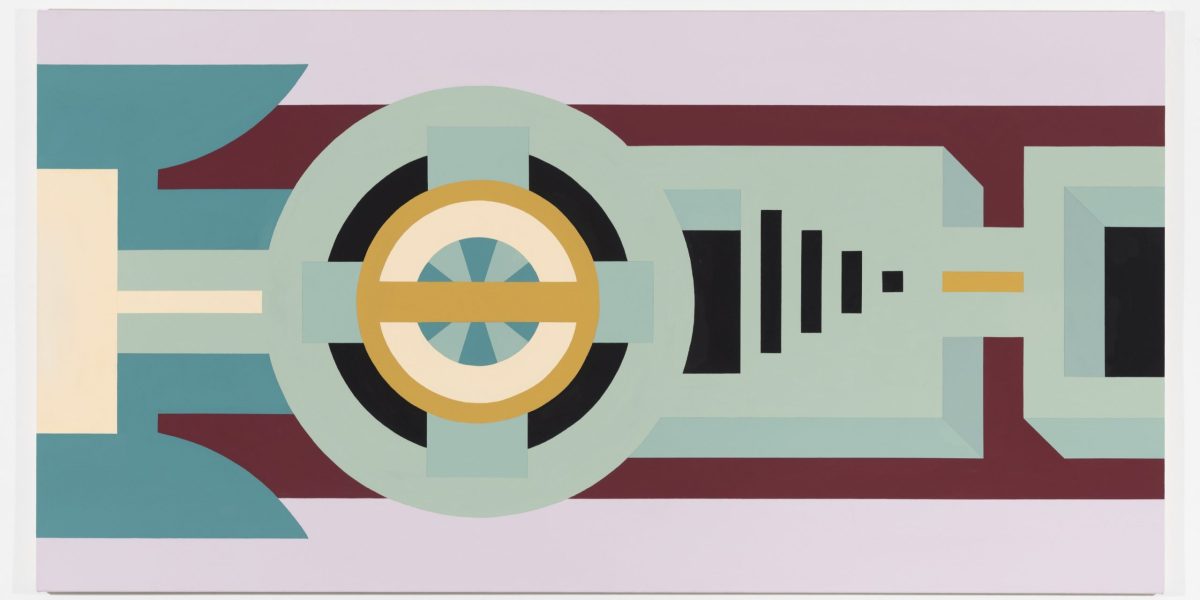

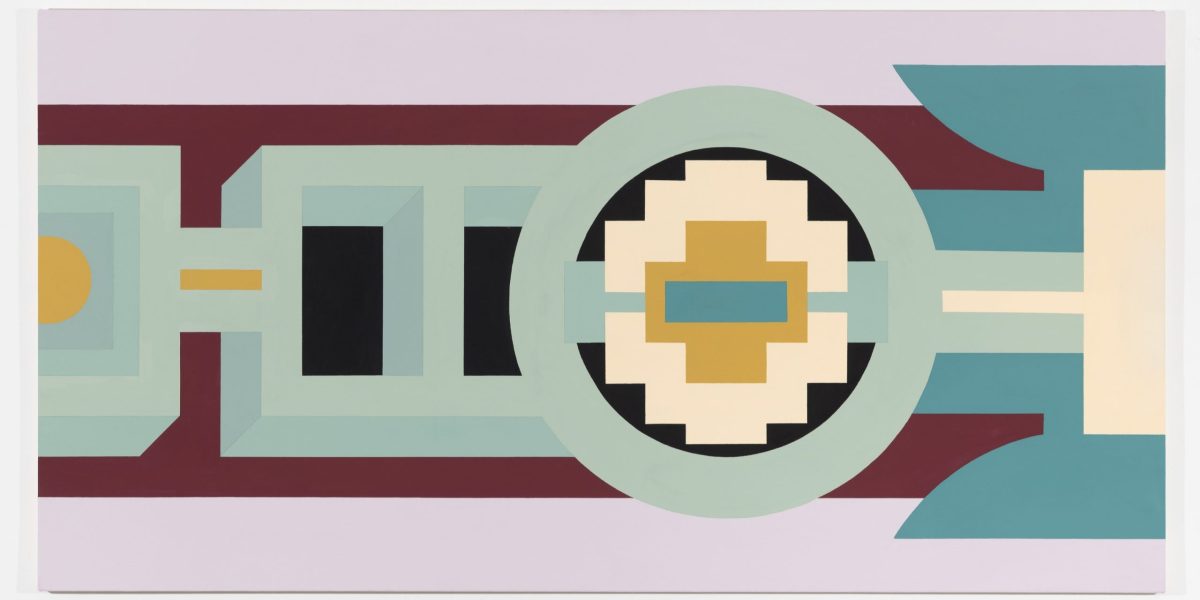

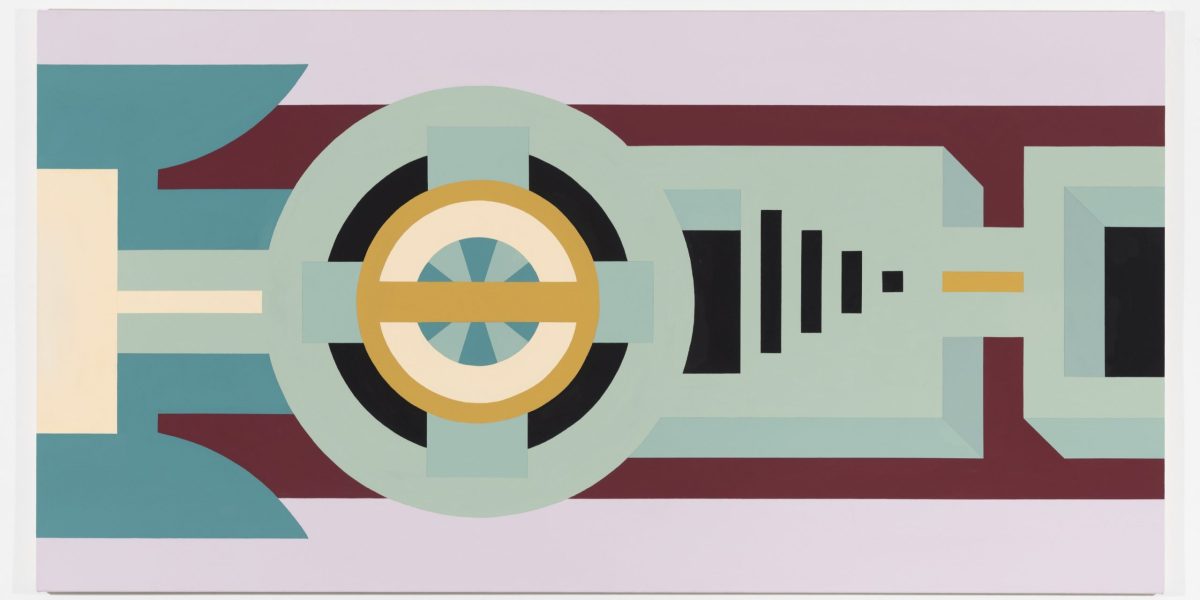

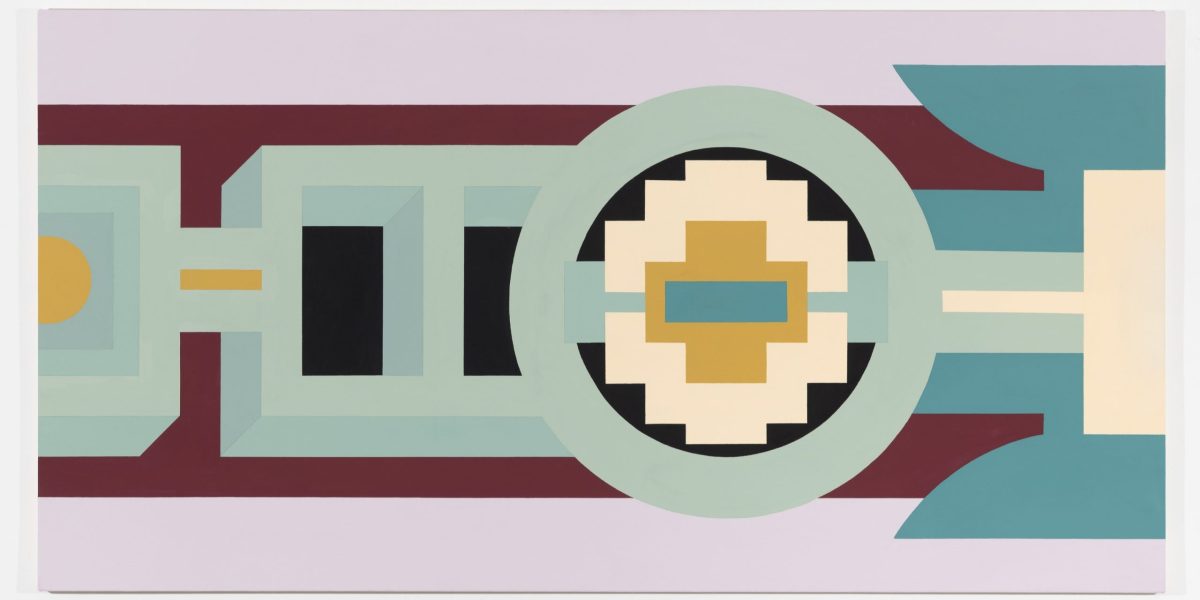

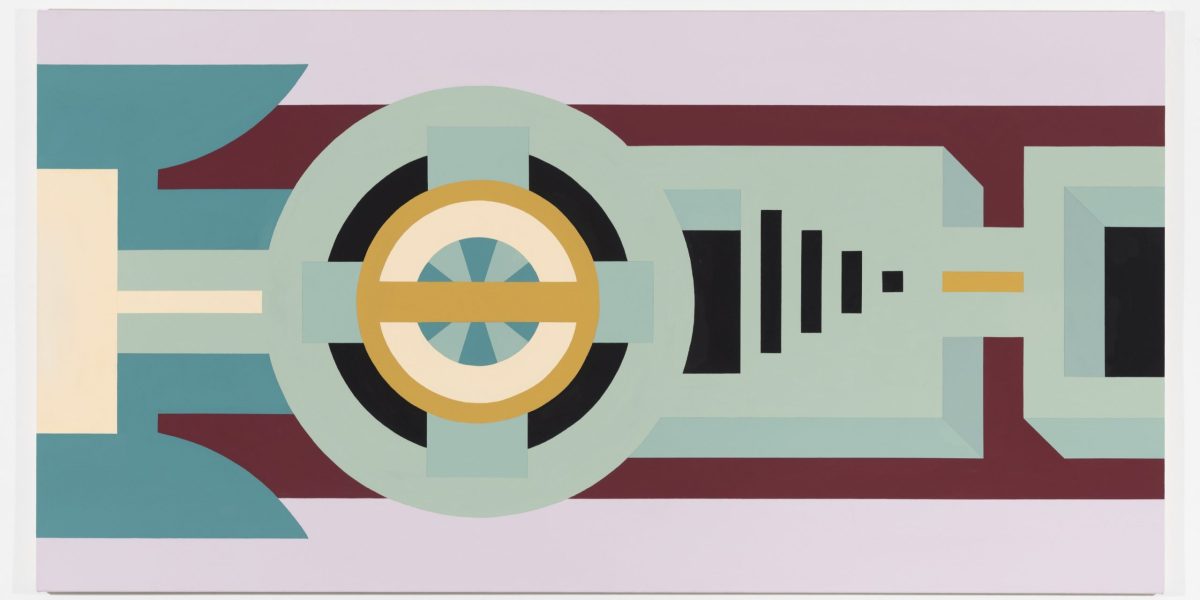

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.

The title, which translates from Irish Gaelic as Bridge of the Fairies, references locations in the Irish landscape which are believed to be thresholds or gateways to other worlds. These sites have spiritual and mythological significance and are attended with respect and superstition. What is your connection to Southend-on-Sea, and how does this public work intend to transform its railway bridge into a threshold of its own?

My connection to Southend-on-Sea is quite recent, and my first visit was to see the gallery and the railway bridge after I was offered the commission in January 2025. I’ve always thought about creating a site-specific work for an architectural space, and this particular bridge became the right moment.

In Irish mythology, thresholds to the Otherworld often appear in the landscape, in places like ancient burial grounds, hills, or wells. I thought it made sense to echo that idea here, using a physical bridge as a symbolic passage. That idea of transformation sits comfortably within my practice, which often incorporates architectural forms as markers of transition or mythic entry points.

Your works often combine ancient historic and future technologies to create ‘retrofuturistic architectures’. I think of your work in conversation with Isabel Nolan, who will represent Ireland at Venice in 2026 and is currently part of Liverpool Biennial 2025, alongside artists like Amba Sayal-Bennett, who have spoken about how their flat, drawing-based practices often manifest in other media, such as three-dimensional sculptures. Are you interested in the practice of architecture beyond the plan and the page?

My work usually begins with detailed drawings mapped out on graph paper. I then transfer those drawings onto canvas or wooden panels, using rulers and measuring tapes to retain the accuracy and structure of the original image.

I really admire the work of Amba Sayal-Bennett. I first saw their work at Modern Forms in Marylebone during Frieze Week in London, and I loved their interpretation of wall-based sculpture. I’m also a big fan of their earlier projection mapping experiments, which I think expanded their language even further between drawing and sculpture. In a similar way, I’d love to experiment more with wall-based and floor-based sculptures. The sculptural works I’ve made so far resemble ambiguous, device-like apparatuses that exist inside the worlds of my paintings, rather than direct extensions of them.

One project I’ve been thinking about involves creating a gallery installation where large-scale paintings act almost architecturally, changing the way the space is navigated. I’m interested in how visual forms can exert physical presence and shift the energy of a room, beyond just being viewed on a wall.

You were born in County Meath in Ireland, and moved to London to study at Chelsea College of Arts in 2021. You continue to exhibit in the country, most recently, at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin (2025), and received an ‘Agility Award’ from the Arts Council (of Ireland) in 2024, which has supported your studio space. Are there differences in the creative funding landscapes in Ireland and the UK?

I received the Agility Award in September 2024, which gave me €5000. I’ve managed to stretch that funding across an entire year, and it has been essential in helping me keep a studio space. An Chomhairle Ealaíon in Ireland offers a wide variety of funding opportunities, but the applications are competitive and difficult to maneuver. Unfortunately, I can’t apply for the Agility Award again this year, and I wasn’t successful with the DYCP grant in the UK. I’m still waiting to hear back from another application, so fingers crossed.

Navigating public funding is always tricky. Both Ireland and the UK have their own challenges, and application processes are consistently convoluted and highly competitive. But, without this kind of support, it’s hard for me to maintain a studio at this moment.

The public nature of the billboards raises questions of representation, also addressed by artist Alice Rekab in their commissions for Liverpool Biennial 2025 and Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) 2025, and by Nico Smith, in their 2024 Bridge Commission as part of Johny Pitts’ exhibition, After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024. You have exhibited at the Irish Embassy in London and co-curated In the Press, a group exhibition of Irish artists in Mayfair with Hypha Studios. What role does curation play in your practice, and concern with representation?

The exhibition In The Press in Mayfair was a project I had been imagining for quite a while, and I've been a long-time fan of the artists involved. Since moving to the UK, it has been harder to keep up with exhibitions by emerging artists in Ireland, but I follow as many as I can on Instagram and try to stay connected like a pop band fanatic in the comments and reactions.

When it came to curating the show, I was eager to talk about the diversity of artistic practice in Ireland right now, spanning artistic media, heritage, and lived experience. This included artists from different parts of the island and Irish artists currently in the UK. It was really fun and wholesome, and we exchanged contacts, family recipes, and tricks of the trade.

In my own practice, I want to be part of that ongoing conversation and community and contribute to the development of new visual languages that reflect the complexity of Irish identity.

You were recently part of New Contemporaries 2025, taking place across venues in Plymouth and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, from which the UK Government Art Collection acquired one of your works. This edition was selected by artists Liz Johnson Artur, Amalia Pica, and Permindar Kaur, the latter having expressed the importance of intergenerational conversations in their practice. What was your experience of this travelling group exhibition?

Being part of New Contemporaries 2025 was a huge moment for me. It gave my practice a real boost in terms of visibility and created a sense of connection with other artists across the UK who are part of the network of alumni. Kiera Blakey (Director) and Seamus McCormack (Senior Curator) were both incredibly generous and supportive. They helped break down some of the intimidating barriers that often surround institutions, simply by being warm and approachable people.

I remember seeing New Contemporaries in 2021, just after I moved to London, and seeing artists Nisa Khan, Hannah Lim, and Rafał Zajko. Then in 2022, I saw work by Tom Bull and Kialy Tihngang and thought how amazing it would be to be part of something like that, and how unattainable it felt at that time in my practice. I know that eligibility has become more open, and I’d really encourage anyone thinking about applying to go for it.

Railway Bridge Commission 2025: Droichead na Sídhe is on view with Focal Point Gallery on Southend High Street until 19 October 2025.

Droichead na Sídhe is a two-part artwork, composed of eight individual acrylic paintings on canvas that have been photographed, digitally enlarged, and assembled into banner-scale prints. Each component engages with a tromp-l’œil technique, where contrasting colours and tones are placed adjacent, suggesting space and depth. These compositions are based on intricate folios from illuminated Celtic manuscripts, and small, chromatic passages you recently encountered in the exhibition, Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300‒50, at the National Gallery in London. Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques? Can you describe your interest in these historical techniques?

I’ve been interested in historical painting techniques since my early days as a painting student at NCAD, between 2017 and 2021. Artists like Piero della Francesca and Sandro Botticelli helped me understand how a painting functions, especially in terms of building strong and balanced compositions. One painting that really stayed with me is The Calumny of Apelles by Botticelli. It’s a small but incredibly rich piece that hangs near the much larger Primavera at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. That painting showed me how visual allegory and metaphor can be embedded through symbols, and strangely enough, it gave me the confidence to move away from representational painting. Around the time I was offered this commission, I visited The National Gallery in London and saw the work of the Sienese Masters for the first time. Their use of colour and architectural perspective naturally found their way into the work.