.jpg)

.jpg)

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

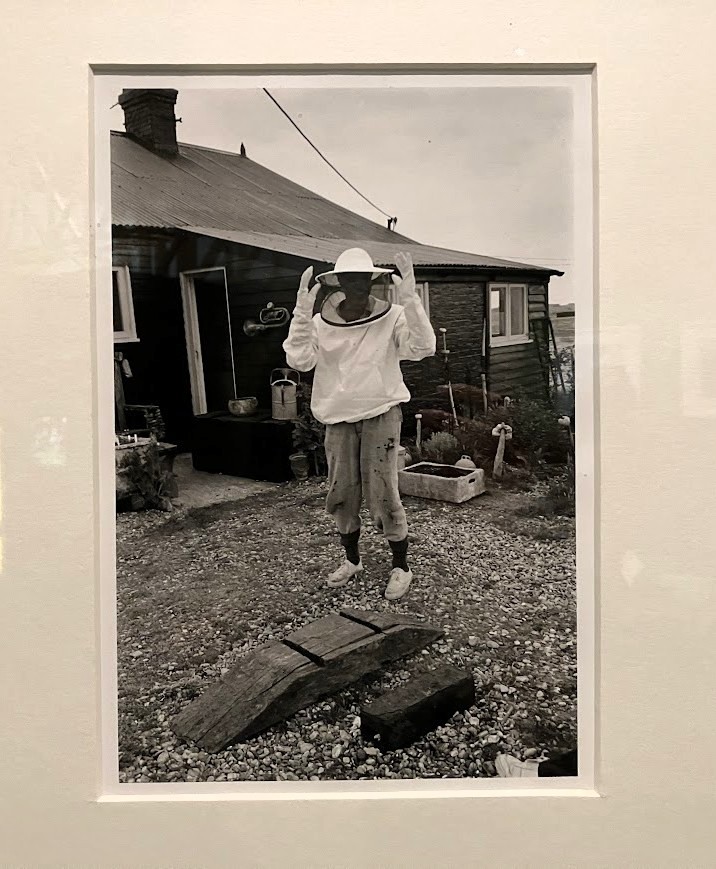

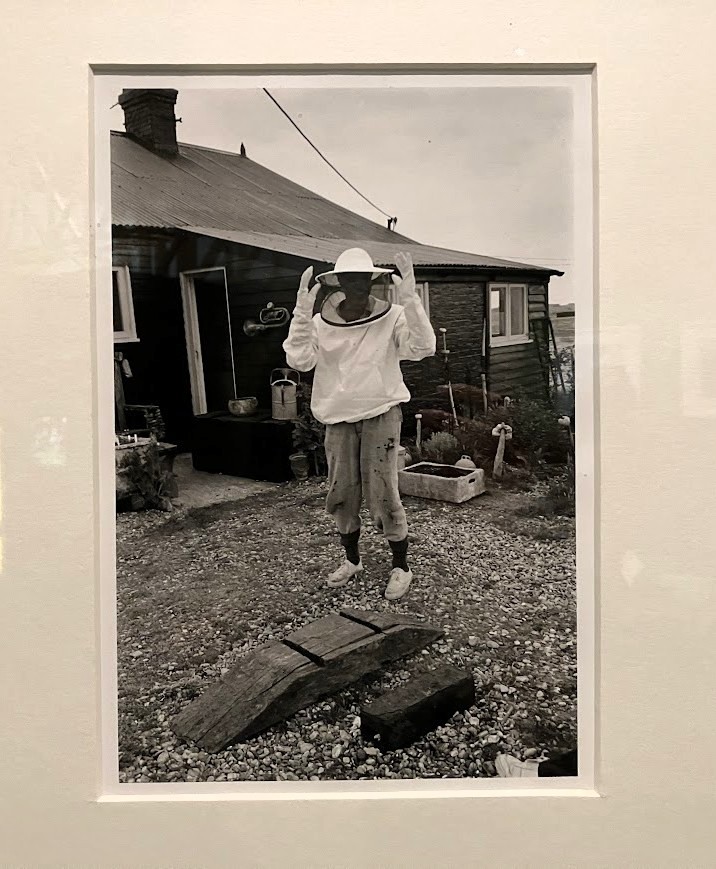

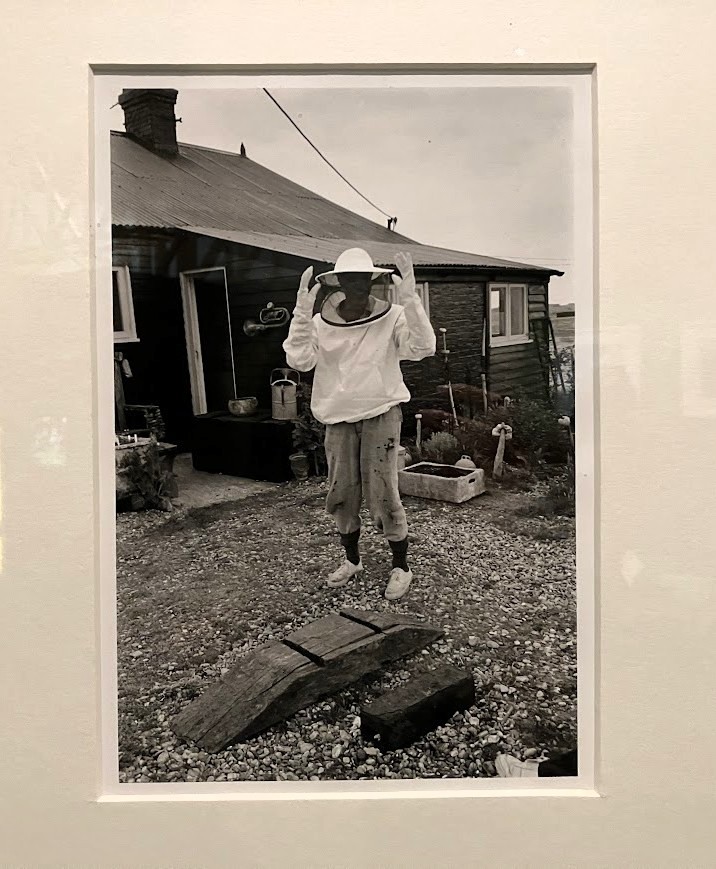

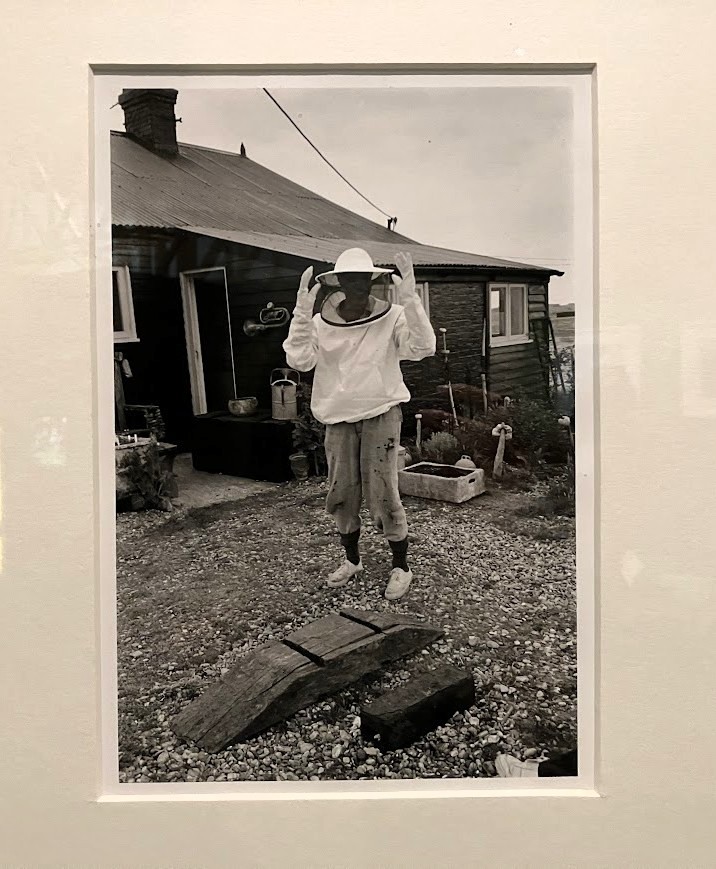

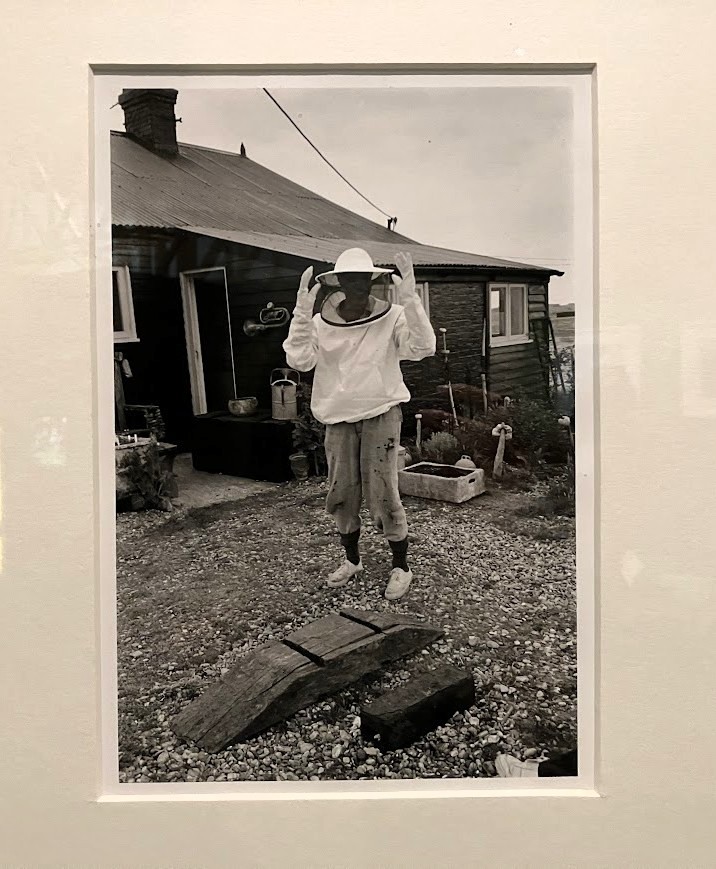

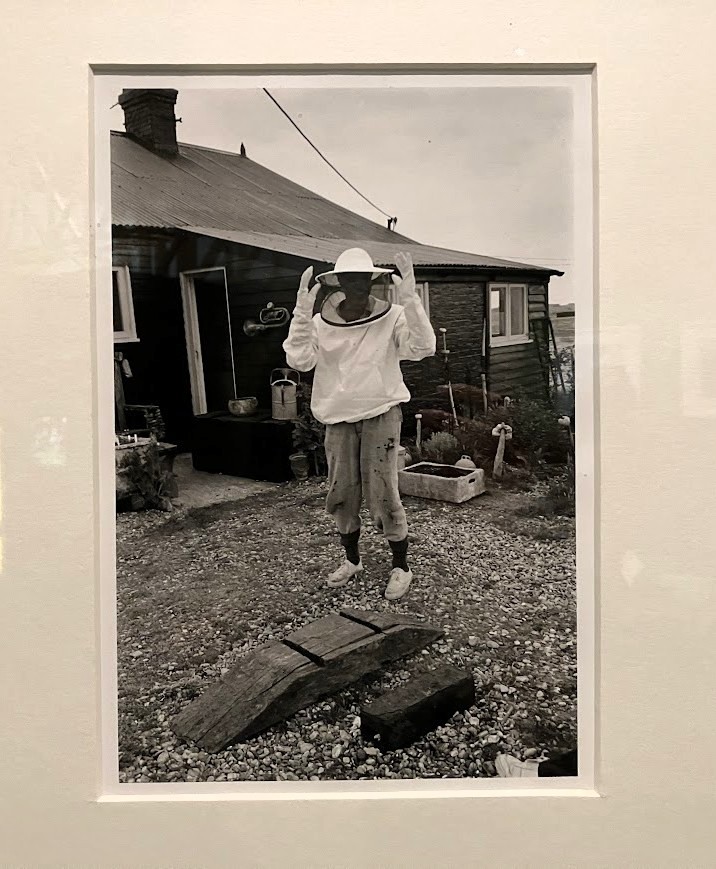

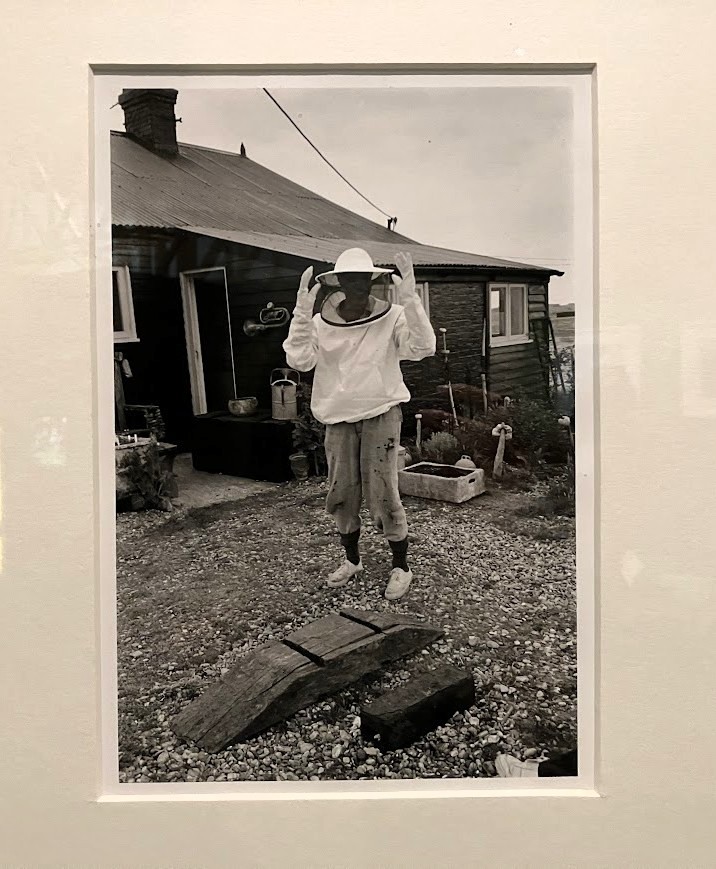

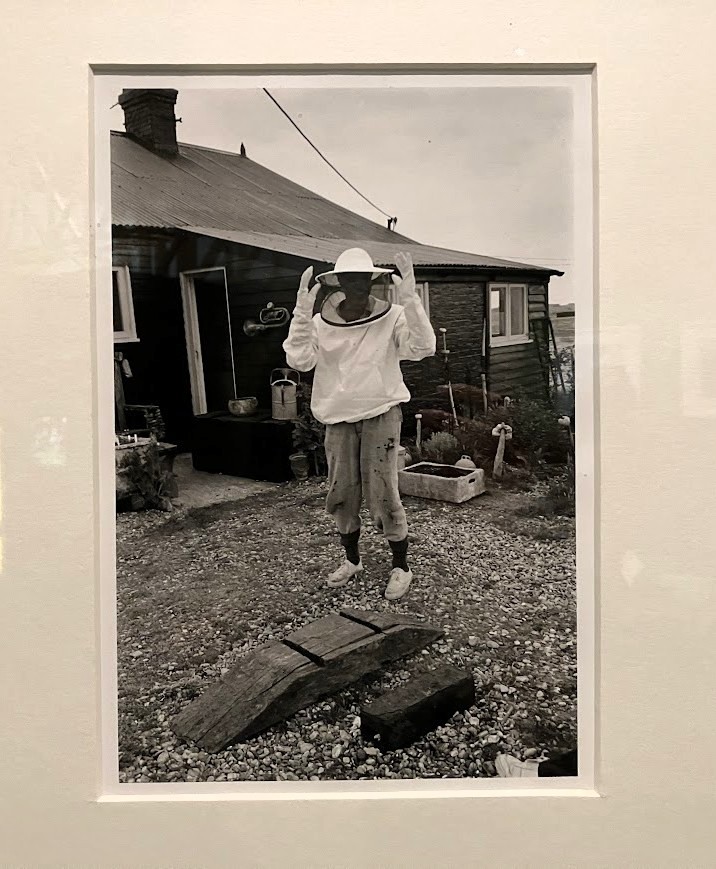

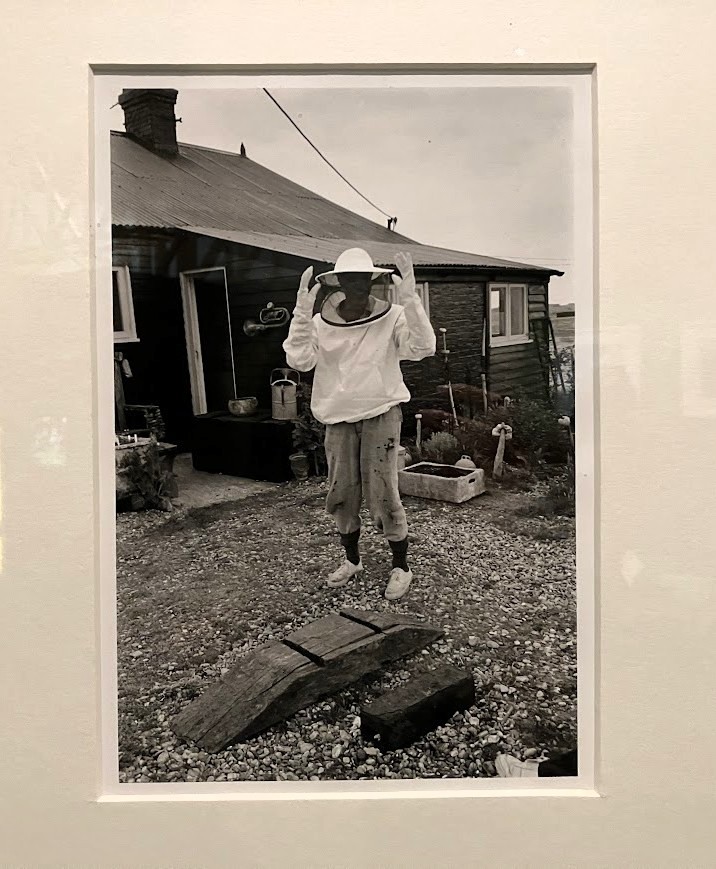

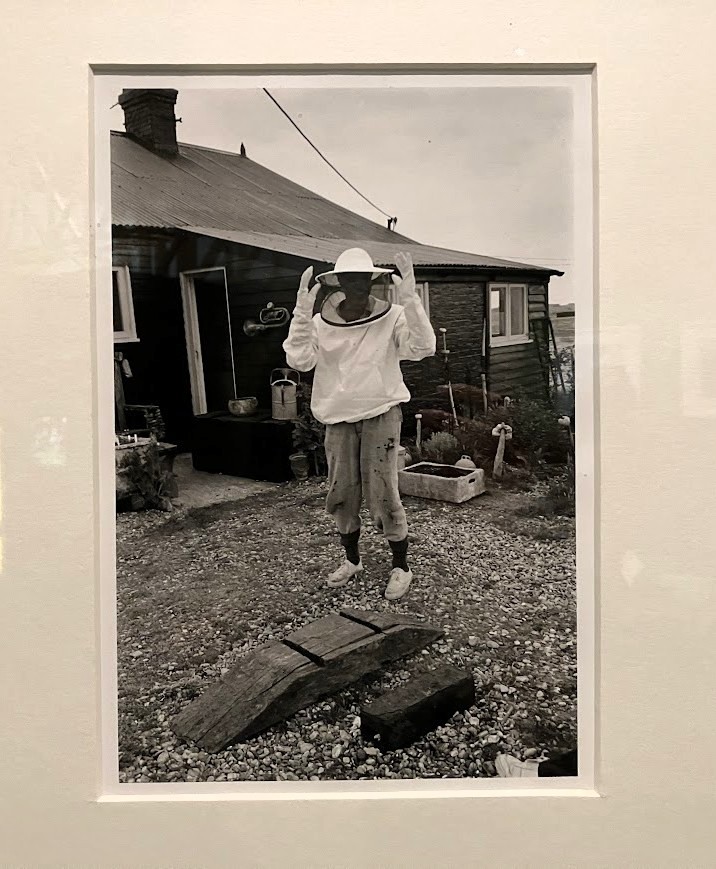

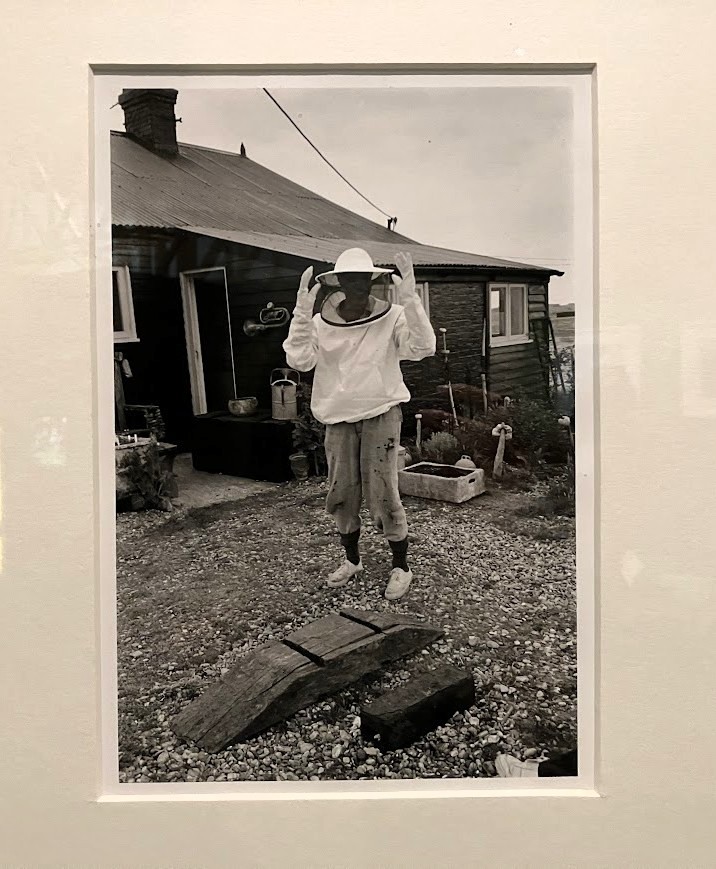

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.

A great number of exhibitions about gardens have sprung up across the UK. Though related to a wider ‘ecological turn’ - and often overlapping in material and content with those concerning more-than-human relations - they nevertheless highlight the very human-centric purposes of gardens. These green spaces are neither ‘wild’ nor wholly ‘natural’ environments, but places where human control over ‘nature’ - and more - is exercised.

It’s unsurprising that Michel Foucault, perhaps best known for his theories of power and prisons, is one of the first thinkers cited in Garden Futures: Designing with Nature at the V&A Dundee. This is an ambitious exhibition and text that can only be realised - and financed - through collaboration. Transplanted from the Vitra Design Museum, which sits near the German-Swiss border, the exhibition offers a dense global survey of landmark landscape designs, featuring the likes of Derek Jarman and Charles Jencks alongside Roberto Burle Marx and Jamaica Kincaid (and, ever present, Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg). It also marks a sustained curatorial engagement by the particular institution with environmental concerns, following the reiteration of A Fragile Correspondence in 2024, the exhibition that represented Scotland at the Venice Architecture Biennale the previous year.

-min.jpg)

The design of the exhibition itself is remarkable, transforming the vast exhibition space into a series of small, private gardens for personal encounters. It reinforces that arts institutions - as indoor spaces - can also be appropriate contexts to explore human relations with the outdoors. Its strength is in its archive, more than its contemporary artworks. The exhibition includes a number of materials relating to settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel, highlighting the confiscation, displacement, and gating off of land, inspired by the work of Ebenezer Howard and other proponents of the Garden City movement in Europe. There is also an early 20th-century Wardian case which, despite its English namesake, can trace its roots to a structure invented by the Scottish botanist Allan Alexander Maconochie a decade earlier. This rare, original structure is sourced from the workshop of the Botanic Garden in Berlin, a continuation of the global histories of plants embedded within the exhibition and interpretation. Just two Victorian Wardian cases ‘survive’ in the UK, one of which was recently installed at Unearthed: The Power of Gardening at the British Library in London, an exhibition rather more down-to-earth in its focus on everyday practices.

-min.jpg)

Still in Scotland, Little Sparta, which is also featured in Garden Futures, is often heralded as the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay’s greatest work. It is, according to the art historian Sir Roy Strong, ‘the most original garden created in Britain since the war’ - a comment that implicitly speaks to Hamilton Finlay’s often combative nature. Many of the 300 works of art, mainly carved in stone, allude to classical thinkers and warriors; some, very directly, to symbols in Nazi and fascist ideologies and visual languages.

-min.jpg)

Open to the public from June to September, Little Sparta is an hour’s drive from Edinburgh in the Pentland Hills, and partnering for the first time with Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF) in August 2025. Hamilton Finlay’s more collaborative projects can be found in and around the city, with Zeljko Kujundzic in SEEDLINGS: Diasporic Imaginaries with Travelling Gallery, and in Jupiter Artland’s retrospective WORK BEGAT WORK, which marks both the artist’s centenary and the extraordinary exhibition by Andy Goldsworthy at the National Galleries of Scotland.

-min.jpg)

Nicky Wilson, the founder of Jupiter Artland, was herself inspired by a visit to Little Sparta, without which, she suggests, the sculpture park and garden would not exist. Finlay visited Jupiter in 2005, early in its formation, situating his neoclassical Temple of Apollo beside a large beech tree. Goldsworthy attended the following autumn and spent many hours in the woodland, resulting in the production of many works, including Clay Tree Wall (2009). These connections between sites, though, are not explicitly referenced in the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition, nor Little Sparta, perhaps limiting the public from travelling further across the networks of Scottish art and artists.

A number of exhibitions in the city make direct reference to the garden - including Siân Davey’s The Garden at Stills, and Yusuke Yamamoto’s The Dappled Garden at the Scottish Gallery. Linder’s Danger Came Smiling travels from the Hayward Gallery in London to Inverleith House Gallery, ‘spilling out’ into the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Best are those less explicit, notably Rooting: Ecology, Extraction and Environmental Emergencies in the University’s Art Collection, which can be found in the Main Library of the University of Edinburgh. The exhibition includes an edition of Hamilton Finlay and Gary Hincks’ Les Femmes de la Révolution, After Anselm Kiefer (1992), which commemorates women of the French Revolution as flowers; indeed, the real things can be found potted on the doorstep of Little Sparta.

Resistance, though, often comes in more subtle forms. At Mermaid Arts Centre in County Wicklow, Composting Colonialism: Towards the Radical Garden brings together a diverse group of Irish, Spanish, and British artists, all considering the legacies of colonialism upon horticulture and the creation of the garden as a status symbol. Marianne Keating's short film They don’t do much in the cane-hole way (2019-2020) meets Wilvie Balmer, a descendant of Irish indentured labourers in Jamaica, paying close attention to the living history of her backyard.

-min.jpg)

This quiet respect for Wilvie’s knowledge - elevated by Keating’s open questions and warm rapport with fellow members of the local community - compliments the filmmaker’s more forceful critiques of British colonialism in the Caribbean, some of which were recently exhibited in Land, an exhibition at Dublin’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. Together, they constitute a series of proposals for what it might mean and look like to ‘decolonise’ post-plantation landscapes, people and environments connected through shared histories of empire.

70% of garden plants in the UK are ‘not native’ to their soils. Yet, these plants have become invisible, assimilated into our ideas around land and national identity. Still, a little digging in the National Museums of Scotland or Dovecot Studios will also unearth the work of Bernat Klein (1922-2014), a pioneering textile designer whose modernist studio in the Scottish Borders has recently been saved at auction. ‘Natural’ colours were central to Klein’s life and work, seeping from their rural surrounds through the large glass windows of Peter Wormesley’s architectural design. The restoration of the studio - and particular plants, such as ‘straight’ chives, that he permitted to live inside of it - will shed more light on the controlled natures of gardeners and artists alike.