Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

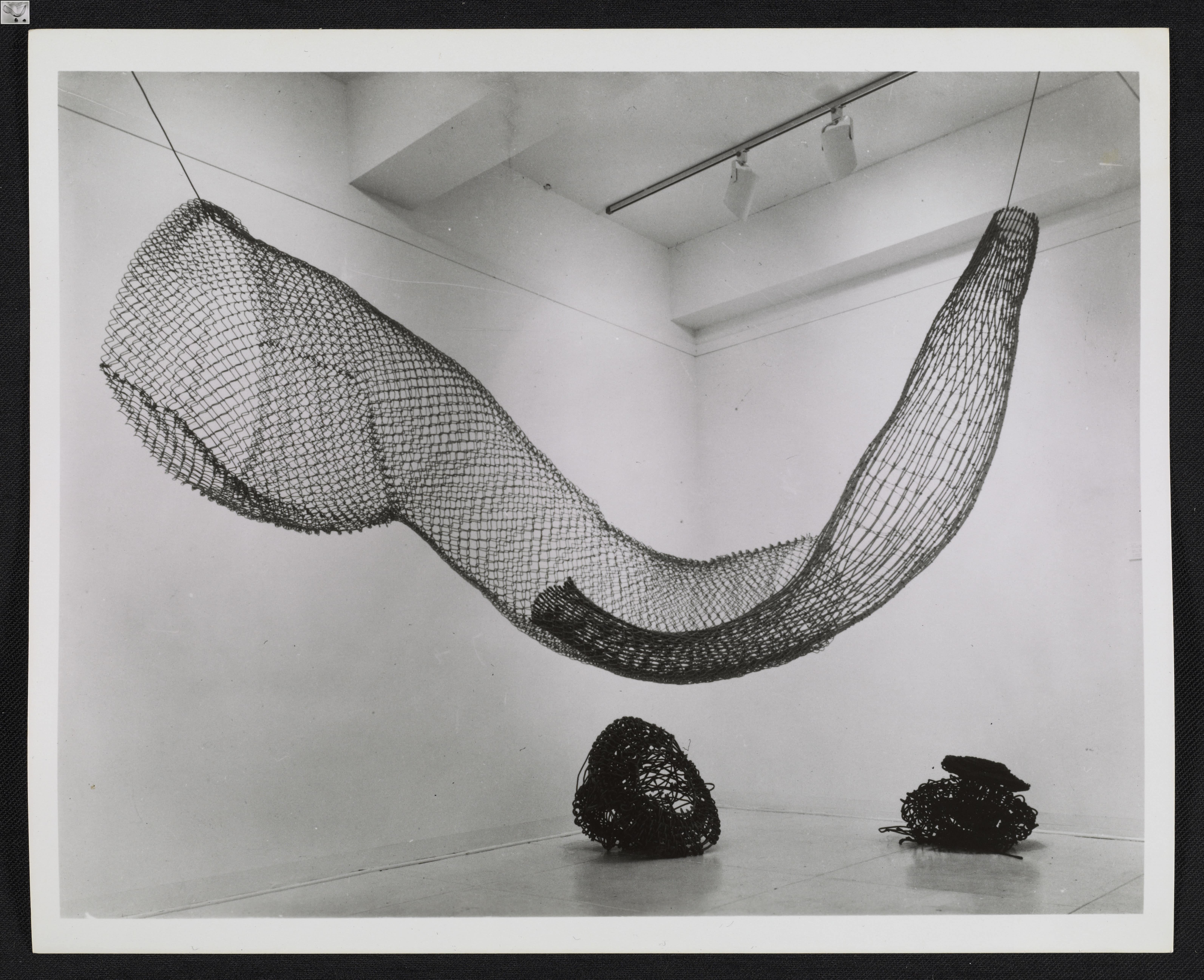

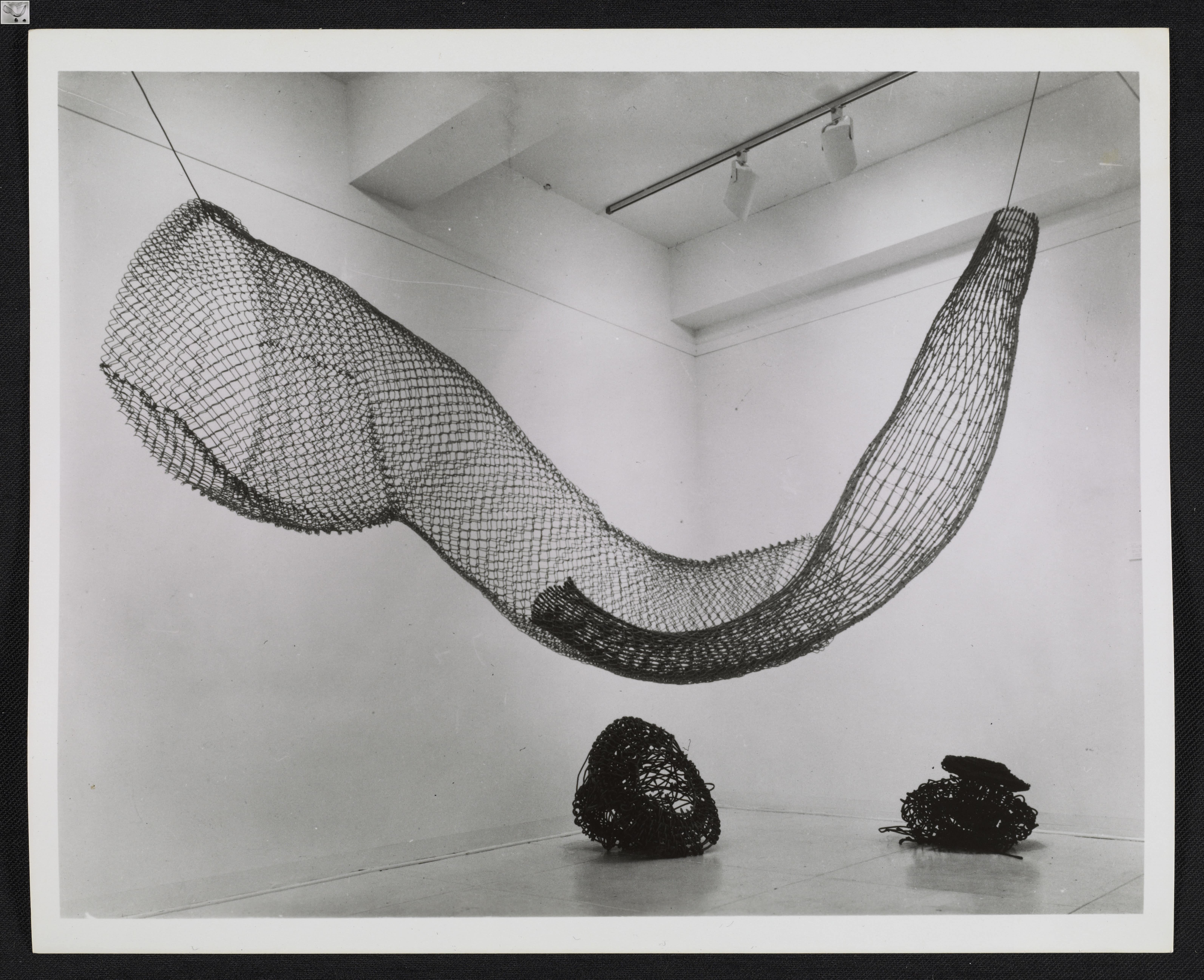

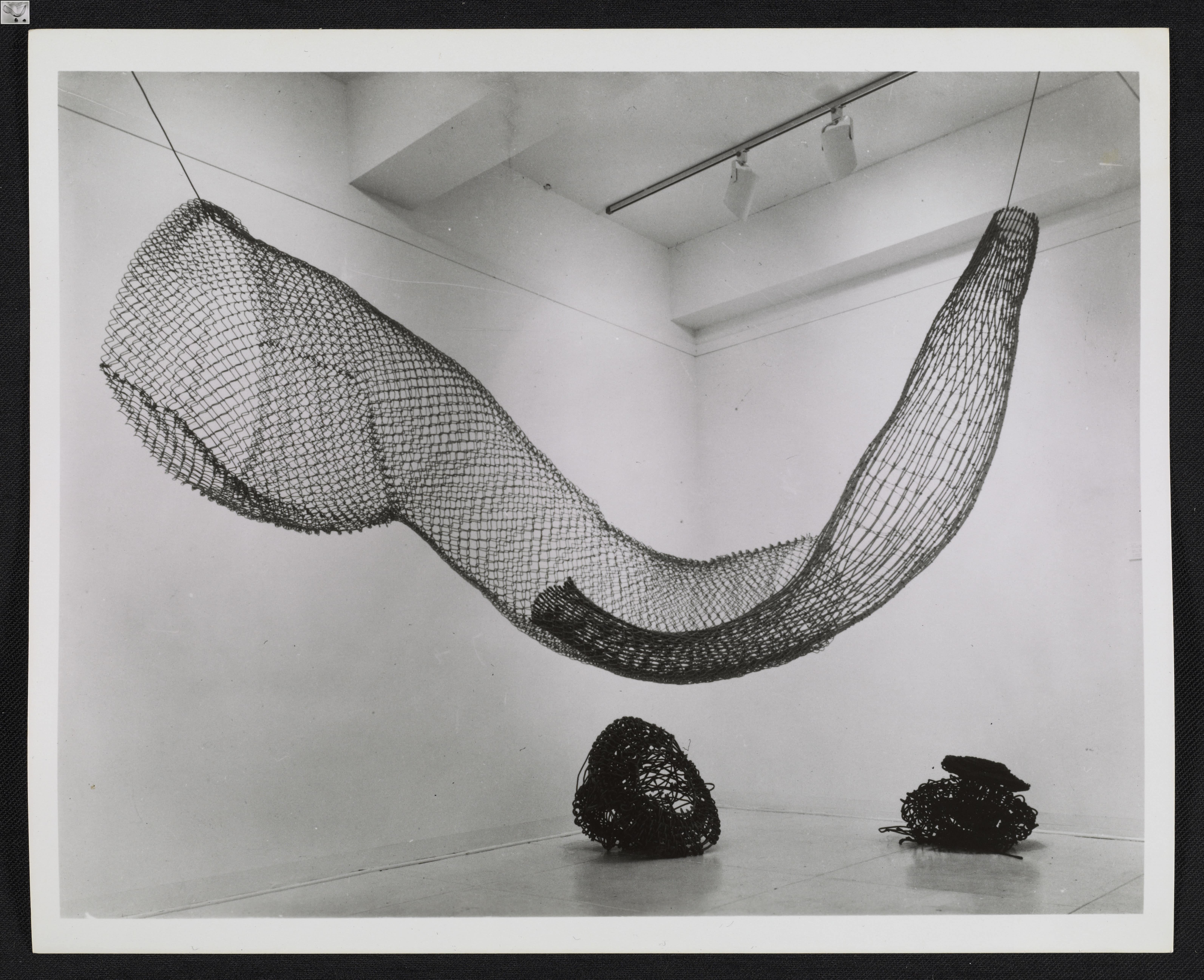

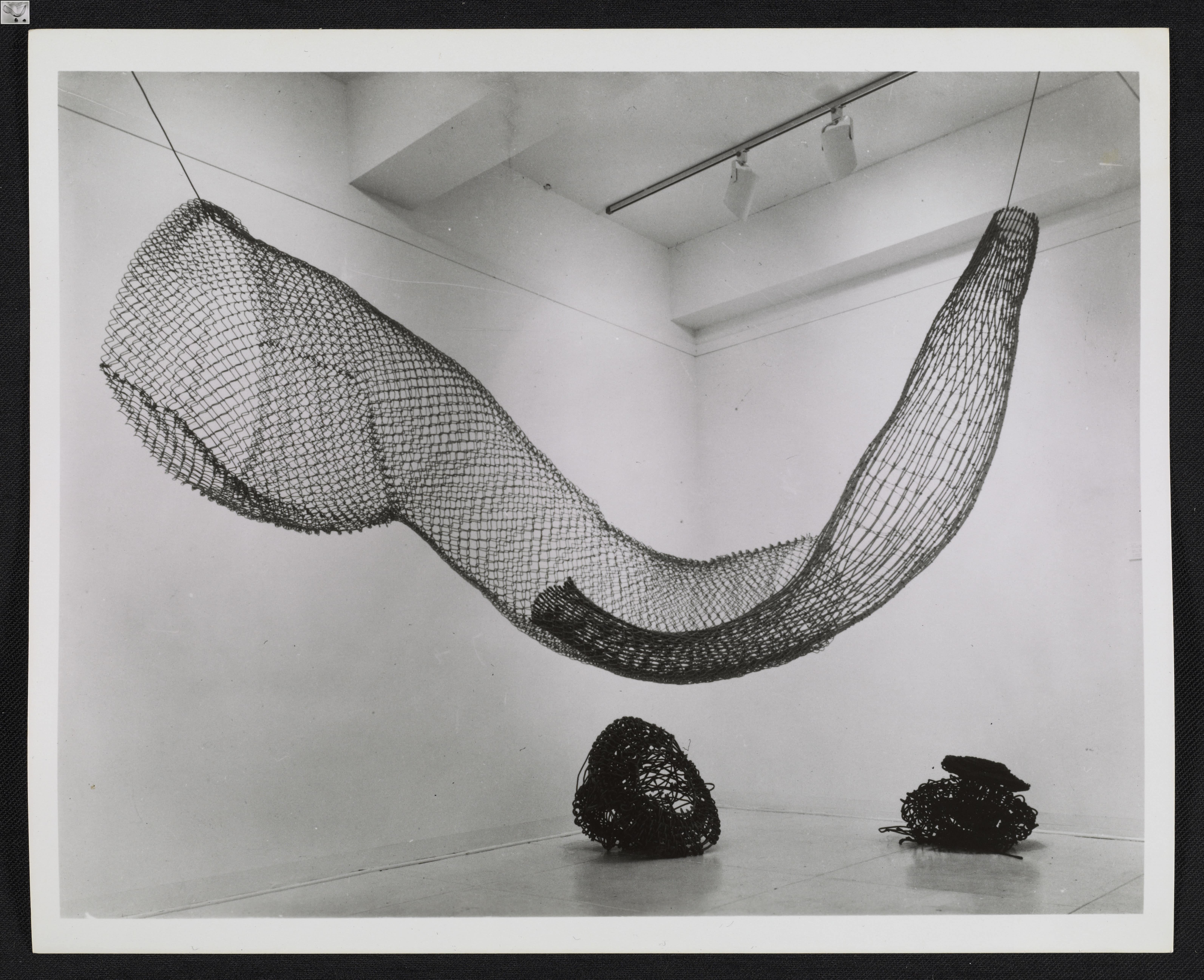

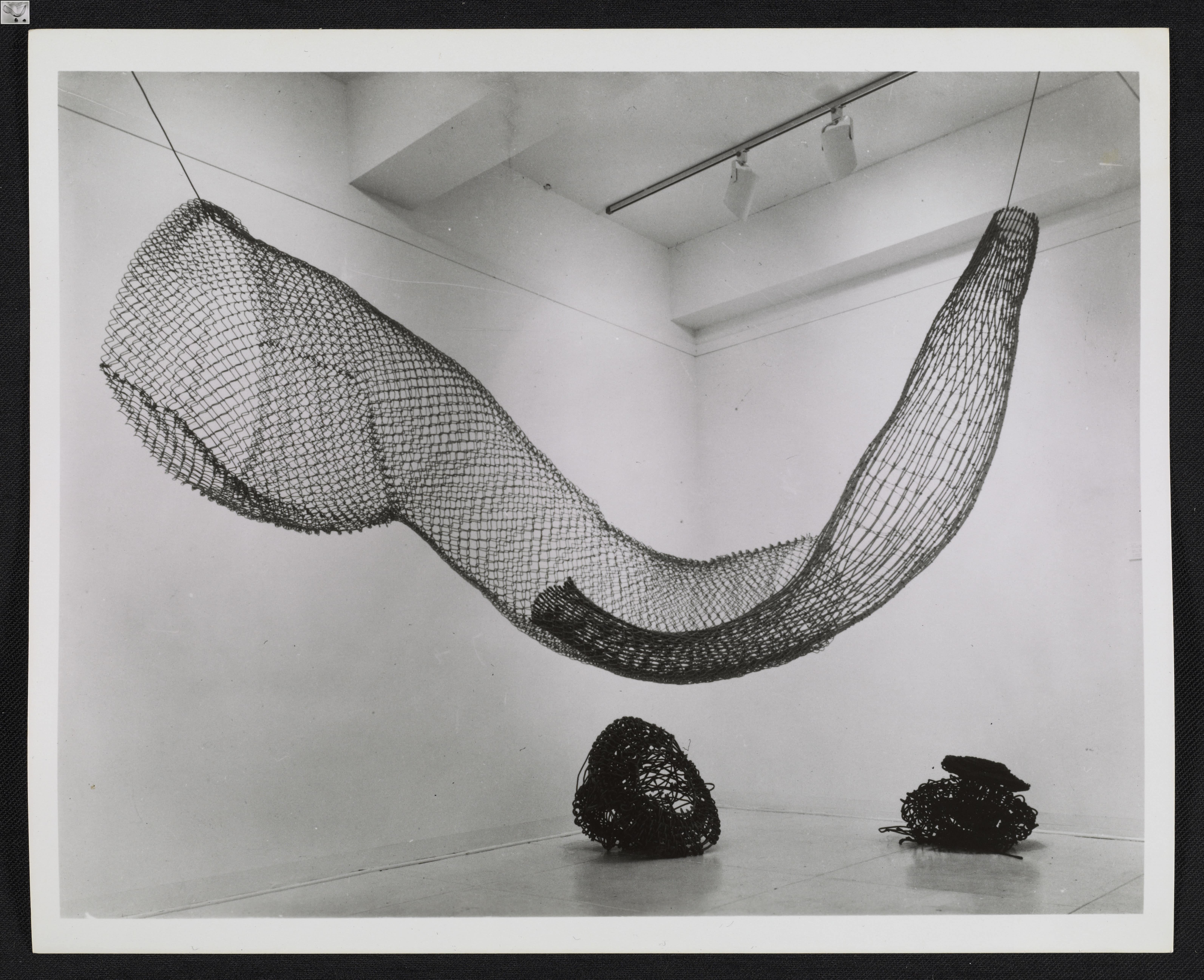

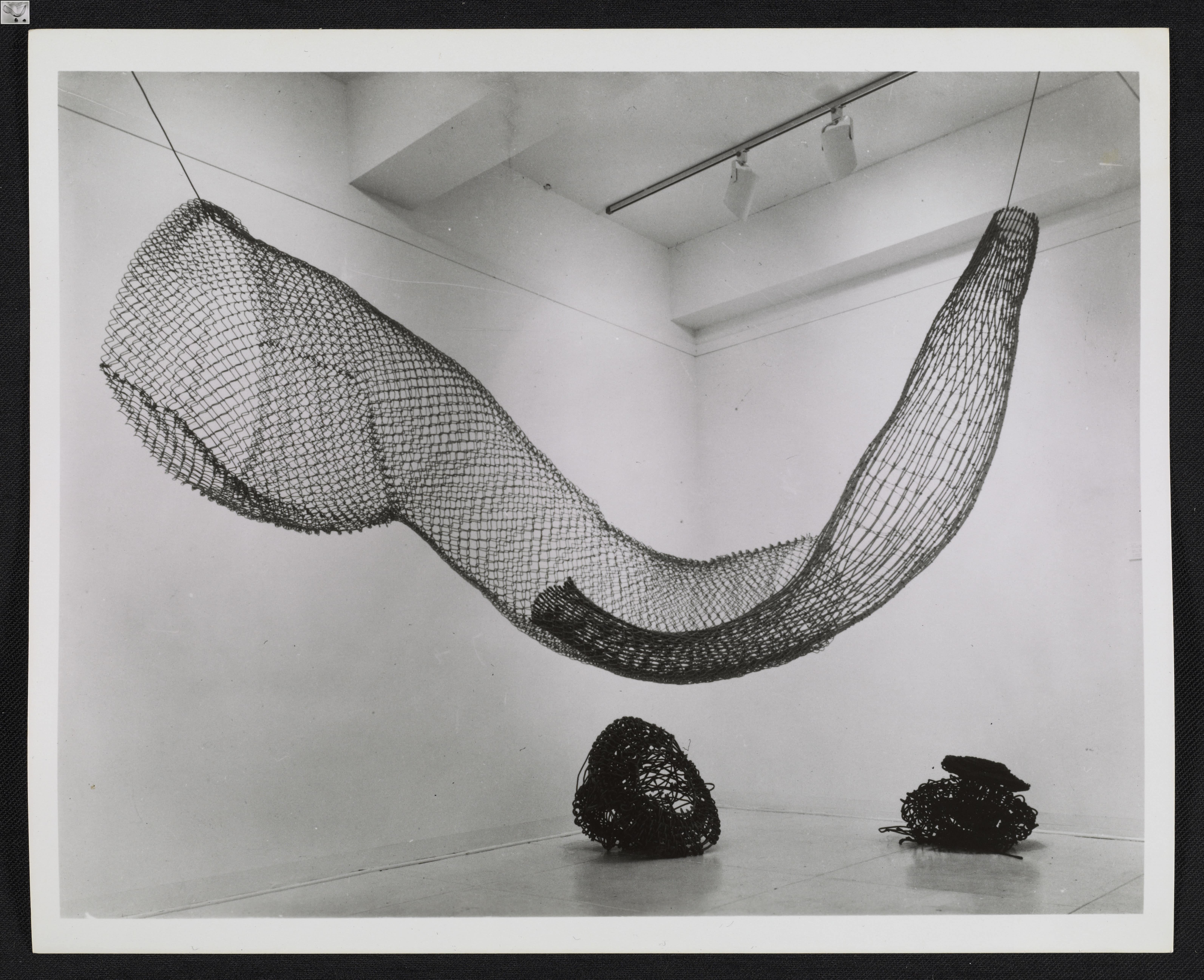

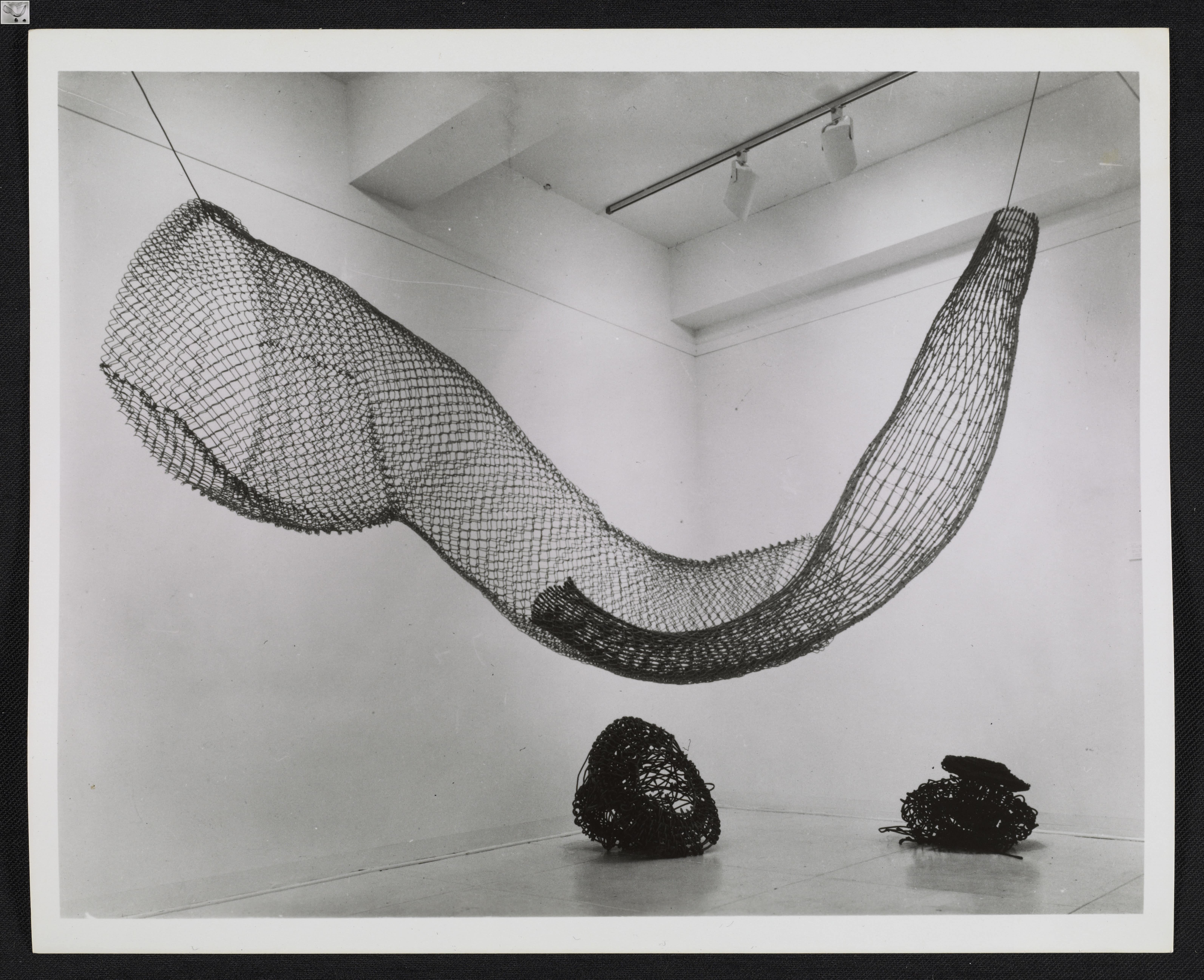

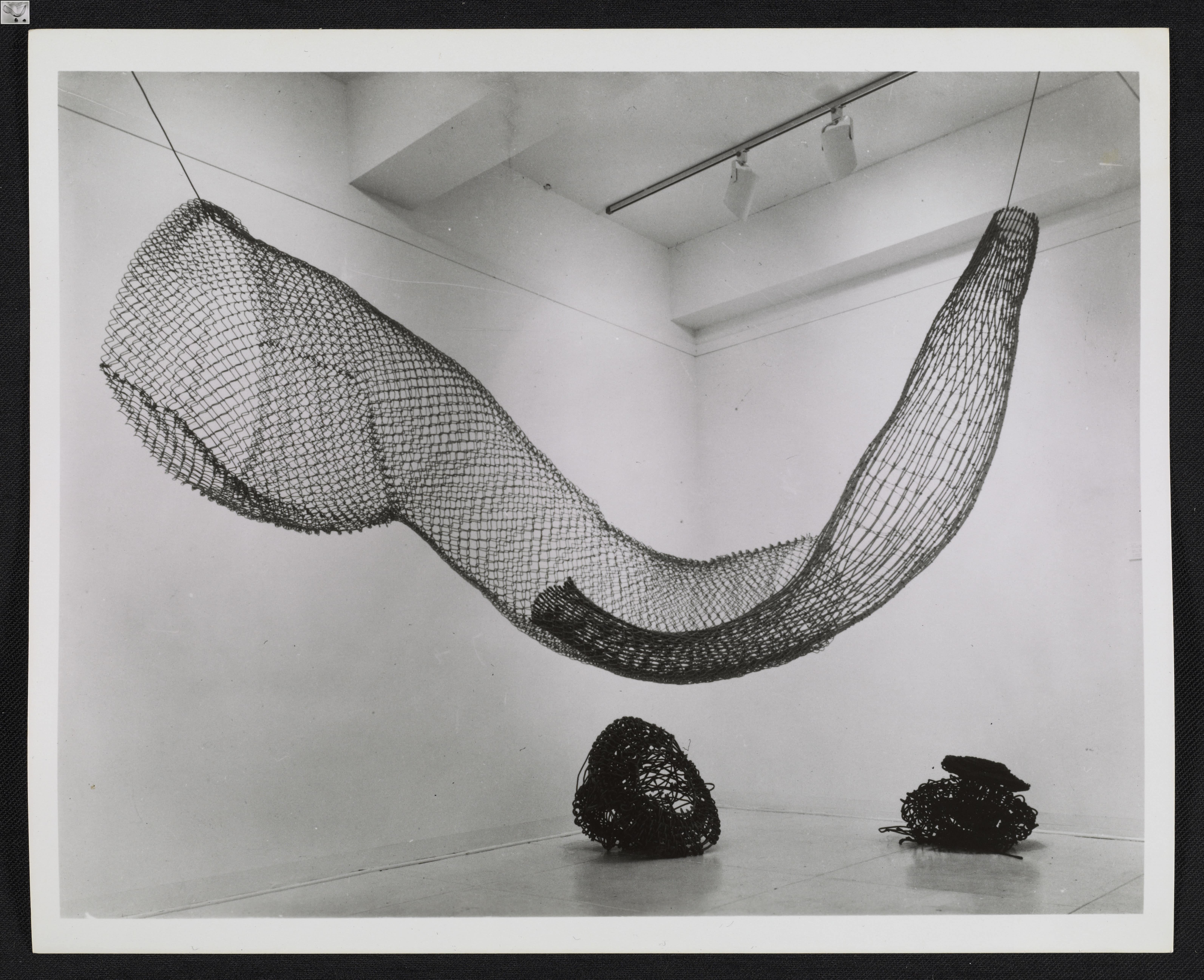

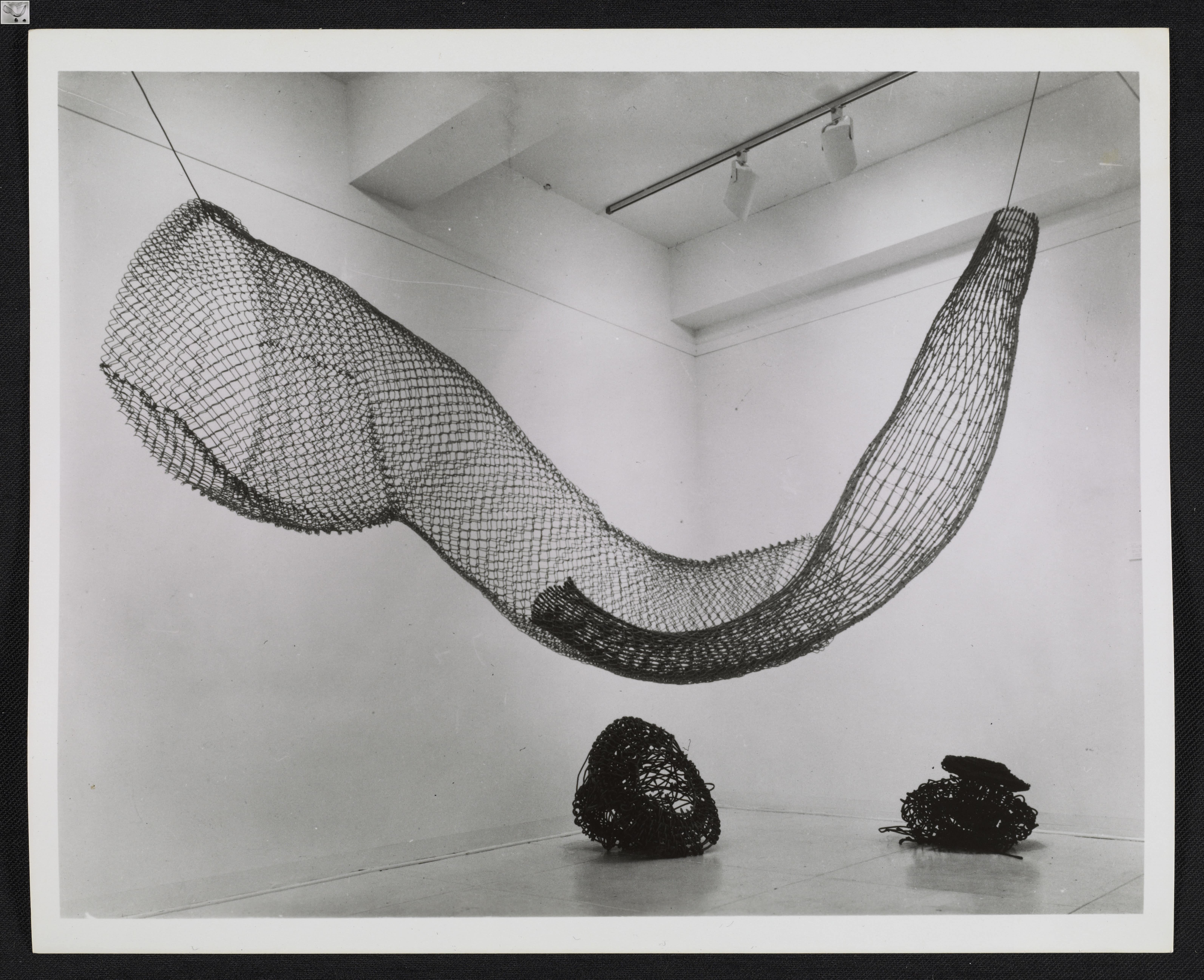

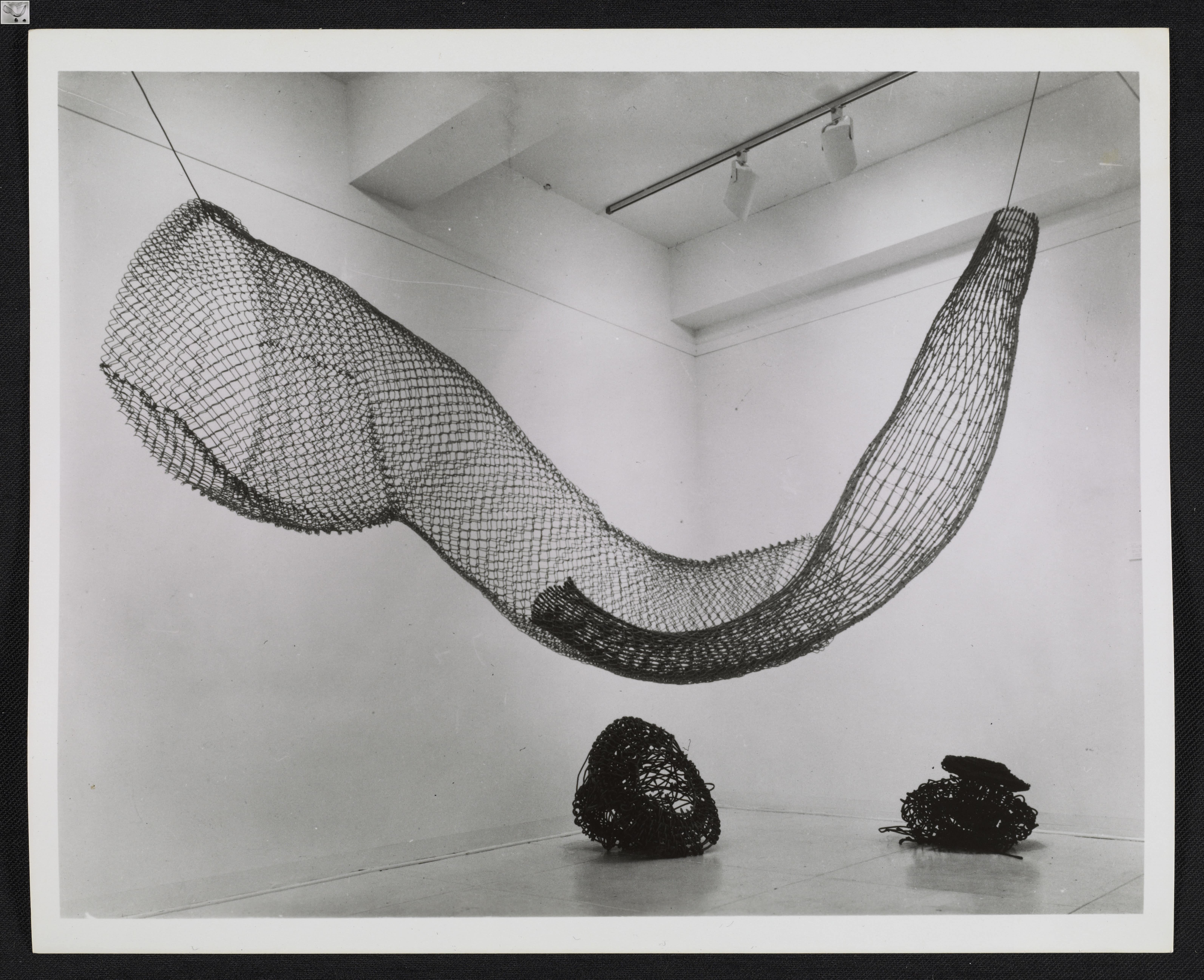

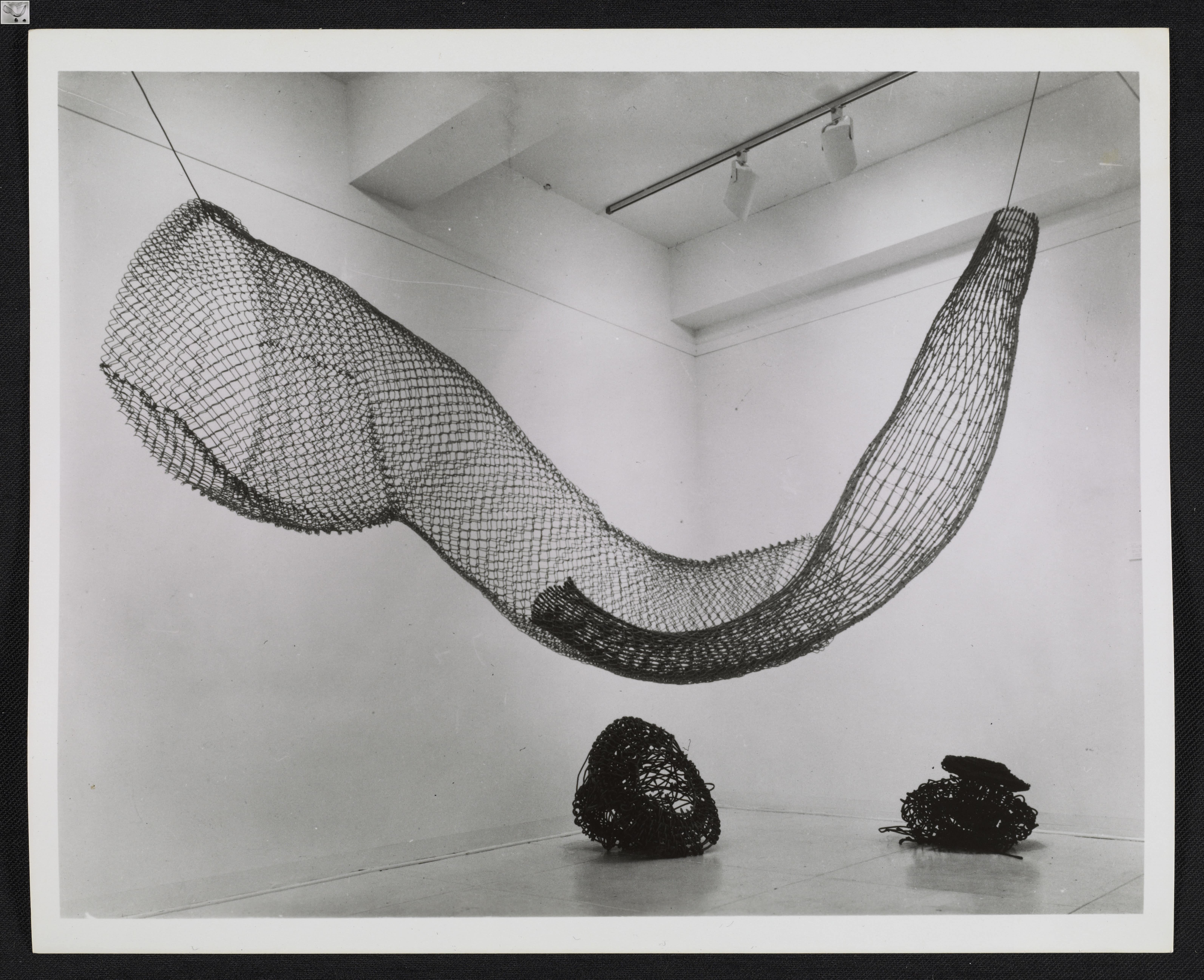

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.

Lesmitaias (2024), the most sensual work in the exhibition, can be found slung over a tree branch in Tramway’s Hidden Gardens. A play on words, which refers to slugs, the idea of something creeping and crawling, is a sort of ‘live sculpture’, resembling overripe fruit or strange sap oozing from the native tree. One of Brazil’s most renowned living sculptors, Pessoa is well-known for their situational sculptures. Lesmitaias, with its allusions to birth and death, recalls the aforementioned hanging works of Hesse, though even more dark and mysterious, even surrealist, with their dusty brown colour and heaped form suggesting potatoes that are growing out of place.

Pessoa’s work has been used to bring forth conversations between the organic and the industrial or brutal, notably in Unravel at the Barbican in 2024. (Nearby, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE would be a new, more cavernous, context, fitting for Bourgeois’ bubbling Avenza too.) Both exhibitions evoke a sense of excavation - either by reference to archaeology, or lesser-known art histories.

Abstract Erotic is particularly well-timed, with Bourgeois’ Maman (1999) returning to Tate Modern. But it provokes its publics to look back, to look closer- and further- towards the great turbine halls across the UK.

Solange Pessoa: Pilgrim Fields is on view at Tramway in Glasgow until 5 October 2025.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams is on view at the Courtauld in London until 14 September 2025.

Abstract Erotic shines light on three artists working in 1960s New York, and their sculptures. As a close study show, it is much closer to The Traumatic Surreal, Patricia Allmer’s tantalising exhibition for the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2024, than more general surveys like Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970, at the Turner Contemporary in Margate. The smaller scale creates space for each artist and more intimate encounters with their practices. The interpretation is plain and straightforward, though the sculptures speak for themselves and, when properly lit, cast shadows that underline their makers’ position and presence.

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse were not a ‘close-knit group’, brought together by their location and connections to conceptual art curator Lucy Lippard, who coined the phrase taken for the exhibition’s title. Overlaps nevertheless exist between their practices and those of their contemporaries. Alice Adams’ wire-like works strongly relate to Gego’s Reticulárea (1969-1982) and hanging works by Ruth Asawa, the latter curtailed by group exhibitions such as the Hayward Gallery’s When Forms Come Alive (2024), which risk undoing the good work of Modern Art Oxford’s 2022 retrospective. But the differences here are more to the point, implicitly defying the homogenisation of women’s work and experiences, including within the singular ‘feminist’ movement.

Rope ties both rooms together. Alice Adams’ little Sheath (1964), woven off-loom, is an animated body of its own, tightly bound yet unravelling at its base. Adams first worked as a weaver and fibre artist; the curators, though, introduce her first works in industrial metals. Adams themselves likened them to fabrics, capable of expansion and compression. Moving through sculptures of different scales - the larger, incorporating the sisal, jute, cord, and hemp of Adams’ early career - highlights the ‘knots and tangles’ within her practice more widely. (More contemporary hand-builders like Otobong Nkanga, represented in New Art Gallery Walsall’s ambitious group exhibition, Earthbound (2024), LR Vandy, and Alaya Ang will have a ball unravelling them.)

The rusted red steel cable choker of Adams’ 22 Tangle (1964-1968) suggests the waste of industrial shipping, a theme picked up by their wooden plank-like Resin Corner Pieces (1967), lined up on the wall like Lubaina Himid’s Aunties (2023). Nearby, light, pearlescent plastics stuff a net sack sculpture by Eva Hesse, which conceals a number of fishermen’s lead weights, again playing with expectations of the media.

Partially reconstructed in 2023, the archive photograph of Adams’ ‘original’ Big Aluminium 2 (1965) suggests other, more biological concerns. Another, lighter-weight aluminium cable was placed inside the sculpture on its first installation in Lippard’s landmark exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, held at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966. This layering creates the appearance of undigested food, resting within the intestines. Crawling along the wall, the work as stands looks forward to contemporary public sculptures like Emii Alrai’s Drinkers of the Wind (2023), ‘an expulsion of feelings from the body’ that the artist has candidly likened with a ‘line of shit or vomit’. Adams’ words also evoke their embodied experiences of the city and built environment - the intense redevelopment of Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s made her ‘feel physically injured’.

This relationship between the body and landscape takes a more performative turn in the work of Louise Bourgeois. Avenza (1968-1969), named after a small village near the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy, is one in a loose series of sculptures, ‘soft landscapes’ which connect ‘mounds and valleys and caves and holes’ with the human body. It also suggests an uprooted subterranean form. Bourgeois often returned to Avenza, creating iterations or variations on the theme, including wearing the bubbling form as a costume in 1947. The Courtauld’s accompanying display of works on paper includes more ambiguous forms, geometric mountains or volcanoes, and a number of clustered, bulbous forms which the artist referred to as cumuls, then drawing from the formation of clouds.

On earth, Pilgrim Fields, Solange Pessoa’s first major exhibition in a UK institution, includes large-scale sculptural forms made from ceramic, bronze, and Hebridean sheep’s wool, produced between Minas Gerais and Glasgow. By bringing together media from Brazil and Scotland, the artist suggests shared experiences of colonial, agricultural, and archaeological extraction that have shaped the landscapes of both places. The exhibition embeds into a strong lineage of site-specific textile environments, often taking on ‘Celtic’ ideas, from Jagoda Buić’s 1970s fibre installations in Dublin, Ireland, the Ulster Museum & Botanic Gardens in Belfast, and Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh - made alongside their Yugoslavian Pavilion at the São Paulo Biennale in 1975 - to Olivia Priya Foster’s truly immersive Black Sheep (2024), one of many strong sculptures and environmental works at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) Graduate Show of the same year.

Like Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran and Jasleen Kaur, Pessoa has brought the outside in to fill Tramway’s vast industrial space. More complex forms, a new body of sculptures, are clustered in nests or strewn as ‘erratic boulders’ across the gallery floor. A spiritual (and local) connection is made by the curators at Glasgow’s ‘industrial cathedral’, likening these forms to Scottish Bronze Age standing stones. More broadly, Pessoa has created an otherworldly environment from earthly materials, including sphagnum mosses to dried Tay water reeds, challenging binaries between other-than-/human beings. The stone-like sculptures also evoke seedpods - the kind that populate science fiction films like Alien (1979) - which are the subject of a concurrent exhibition with Travelling Gallery in Scotland, including Alrai and Amba Sayal-Bennett, another contemporary artist exploring abstraction in the context of migration and diasporic identity.

Degradation is also represented in Scotland’s contemporary sculptural landscape, with Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite (2025) now part of a group exhibition at Common Guild in Glasgow, and Mella Shaw’s new ceramic installation exploring the catastrophic effects of marine sound pollution on whale species in Dundee. Pessoa’s work, too, could easily make a home in Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket (now showing Mike Nelson), or other transport terminus.